Why have we never returned to the Moon? There are many reasons, from lack of funding to political will. It's clear the days of the Space Race between the Soviet and US super powers are long gone. Yet fifty years after Apollo we’re in a new, more competitive dawn of lunar exploration, this time featuring players from all over the world.

The Beresheet robotic spacecraft – the first privately funded Israeli mission – attempted a lunar landing on 11 April this year.

While their effort crashed, it did reach the surface and proved that any country, any company, no matter how small, can participate in lunar missions.

You just need the budget, know-how and drive to succeed.

- How the Apollo landings changed the world forever

- Apollo Moon landing conspiracies crushed

- How NASA filmed the Moon landing

SpaceX, Blue Origin and other larger commercial space companies have shared plans of their autonomous lunar missions.Moreover, they are not alone.

China and India are growing space powers and more nations are continuing to emerge.

An exciting time is upon us and launch schedules are getting busy, as everyone is racing back to the Moon.

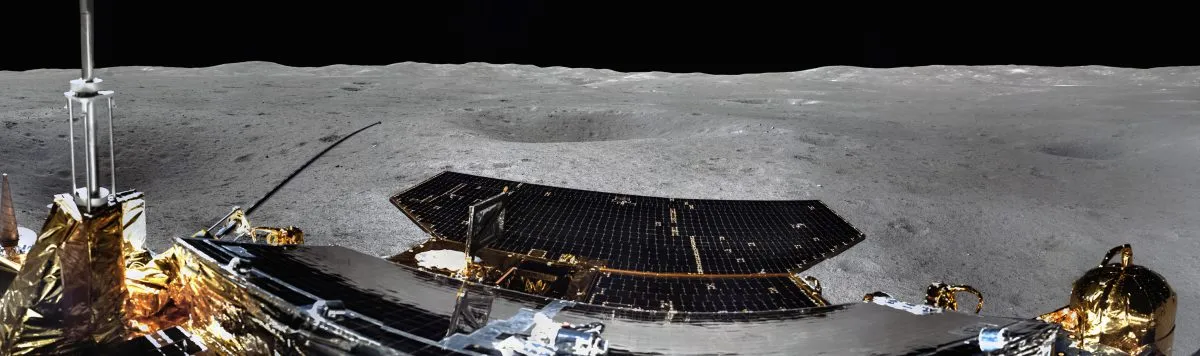

The China National Space Administration successfully launched its Chang’e 4 lunar lander to the South Pole Aitken basin on the Moon’s far side in January 2019 and deployed its Yutu 2 Rover.

Using the knowledge that they gained from this mission, they are developing technologies for their later Chang’e 5 and 6 stages.

These are all part of an extensive lunar exploration programme, the ultimate goal of which is to perform a crewed mission landing in the 2030s to establish a permanent Chinese outpost near the South Pole.

India’s Chandrayaan-2, which at the time of writing has a launch date of 15 July, will be the second mission to the Moon for the nation.

Including an orbiter and lander-rover module, IRSO aims to gain a better understanding of the origin and evolution of the Moon with the mission.

Like China, India offers to have a human space programme and a crewed orbital vehicle, called Gaganyaan.

Designed to carry three people, ISRO plans on launching this three-person mission to orbit the Moon for seven days, in late 2021.

Equal players With this rapid activity from these emerging space players, the playing field has been levelled.

The larger, more established agencies such as NASA and Russia’s Roscosmos are now pitched equally against these smaller agencies, who are each making their claim on the Moon.

Roscosmos is planning a series of lunar robotic missions. Firstly, the Luna-25 mission, due to launch in 2021, aims to land near the lunar south pole and analyse regolith samples.

Then the Luna-26 mission will study the Moon from low polar orbit and finally, the Luna-27 landing mission will partner with ESA as part of a study to see how future missions could utilise the resources already found on the Moon.

It is due to launch in 2024. NASA, meanwhile, has more ambitious plans.

NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine announced earlier this year its intentions to attempt to touch down at the lunar South Pole by 2024, with a crew that will include the first woman to set foot on the Moon.

Named the Artemis mission, this is phase one of a much larger ambition to establish a sustainable human presence on the Moon by 2028, and then go onwards to Mars by the 2030s.

“The most significant component of NASA’s lunar aspirations is the construction of a new Moon-orbiting outpost called the Gateway,” says Michael Interbartolo, one of NASA’s moonshot navigators guiding their lunar plans at Johnson Space Center.

“The Gateway will be a command module which, once established, will continuously orbit the Moon on a near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO), ranging from 1,500km to 70,000km from the lunar surface.

“The Gateway will initially be constructed to complete Phase 1 of the mission – the return of humans to the Moon – and will be composed of a power and propulsion element contracted to Maxar Technologies in May 2019 and a mini-habitat element soon to be contracted.

"In 2024, when the SLS (Space Launch System) and Orion spacecraft are ready for launch, four astronauts will arrive at the Gateway for a 30-day mission.”

After this ‘first boots’ phase is complete, the second phase of Gateway construction begins.And collaboration is key to its success.

Building on the agreements in place for the International Space Station, agencies such as NASA, Roscosmos, the Canadian Space Agency, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency and ESA will participate in a range of human and robotic exploration using the Gateway.

“European ministers in charge of space activities will meet in November to finalise ESA’s vision for the future of Europe in space and we will be proposing to participate with NASA in the Lunar Gateway,” says Didier Schmitt, the coordinator for human and robotic exploration at this ministerial meeting.

ESA hopes to provide several elements including a habitation module, advanced telecommunications, propulsion systems and a science airlock system.

“As you know with space, it’s all about what you can barter. By providing these modules, we would hope to be in a strong position to have an ESA astronaut on the Gateway by 2027,” says Schmitt.

After 2028, it is hoped that after several short sortie missions to the lunar surface, we can understand better how to establish a Moon base at the South Pole.

Michael Interbartolo, NASA moonshot navigator, Johnson Space Center

A spirit of collaboration Several other ISS-partnering countries have expressed an interest in collaboration.

“Canada has made an agreement to provide the robotic arm, and JAXA and Roscosmos are also in talks with Bridestine,” Interbartolo confirms.

It appears that this could become as international as the space station.

“Once Phase 2 is established, it is envisaged that human lunar missions will occur once a year, lasting between 30 to 90 days, depending on capabilities,” says Interbartolo.

While it won’t be a permanently crewed craft like the ISS, science would be robotically achieved or controlled remotely from the ground. And then, after 2028, it is hoped that after several short sortie missions to the lunar surface, we can understand better how to establish a Moon base at the South Pole.

“We can learn a lot from long-duration stays on the lunar surface, as we have no gauge on the human physiology in a partial gravity environment,” he explains.

“We know a lot about the crews on the ISS with bone and muscle loss, but maybe the gravity on the Moon is sufficient to prevent these effects. We can learn more about the use of robotic caretakers on these long-duration missions, doing the dull stuff so that our astronauts can achieve more scientifically valid work.

"If we can use the Moon – just two days away – to prove these expeditionary logistics, we’re in a better position to understand how all these technologies are going to work when we’re 400 days away.”

We are at a turning point in the history of space exploration and development, on the cusp of a revolution where new industries are being born that will use space in new ways.

Fifty years ago, it was politics that drove the Space Race, perhaps this time will be driven by profit, innovation and public interest.

Either way, collaboration is key, if we are to truly embrace this new dawn of exploration.

Why would we go back to the surface of the Moon?

The South Pole crater has been selected for exploration by many space players.

As ESA’s Didier Schmitt explains, “We know that it is rich in water resources, which we can hydrolyse for propellant (as hydrogen) and oxygen for the crew.

"Also, the South Pole has collected all the material from the interior of the Moon when it cooled some 4 billion years ago.

"Such craters are cold traps that contain a fossil record of the early Solar System. We can learn a lot about our origins.”

“A key strategy to the successful location of a permanent base will be in situ resource utilisation (ISRU),” says Aidan Cowley, ESA science advisor to future missions at the Astronaut Centre, where he and his team have developed a material that simulates lunar regolith (loose deposits covering solid rock).

“We begin construction of a lunar facility later this year, using 600 tonnes of this simulant, to prepare our astronauts, to test equipment and to validate operations on the lunar surface.”

Of appeal to the commercial sector is the potential range of metals and materials available at the South Pole, and their resale value.

While there are some existing treaties in place over who can claim ownership of what beyond Earth, (Outer Space Treaty 1967, Mining Space Act 2015), with so many people heading towards the Moon, these rules may require reclassification.

Why has there been such a gap between Apollo and our return to the Moon?

Space stations and robotic science missions have been the main focus of space exploration since the Apollo missions ended in 1972.

Since then, human trips to space have been limited to low-Earth orbit.

Without the political agenda of the Space Race, governments weren’t interested in funding a space programme.

And in a way, we needed to wait for the rise of commercial space, for launch costs to decrease, for new innovations to emerge such as faster prototyping, the advances in additive manufacturing, artificial intelligence and robotics – all these technologies can be adapted for applications on the lunar surface.

With the emergence of China and India and commercial space companies that weren’t around 50 years ago, perhaps it forced the US and the other more prominent space agencies to rally together and realise that it was time to go back.

It was time to return to the Moon together, not just for ‘footprints and flags’, but to live and explore.

And to begin the permanent presence out into the expanse of space, and beyond the cradle of Earth.

Niamh Shaw is a science communicator, engineer and performer. This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.