There's a new star due to appear in the night sky sometime soon, and it's possible that the same event was seen and written about by a German abbott in the early 13th century.

Astronomers are still awaiting the nova event that will see a 'new star' visible in the night sky, known as the T Coronae Borealis nova.

This isn't literally a new star, however.

'Nova' means 'new star', and these events are so-called because they amount to the sudden brightening of a previously-dim star in the night sky, to the point that it reaches naked-eye brightness.

When a nova occurs, it appears there is now a bright star where no star (or a dim star) was visible before.

Historic sightings

T Coronae Borealis (T CrB) is a recurring nova, which means it predictably appears within set timescales.

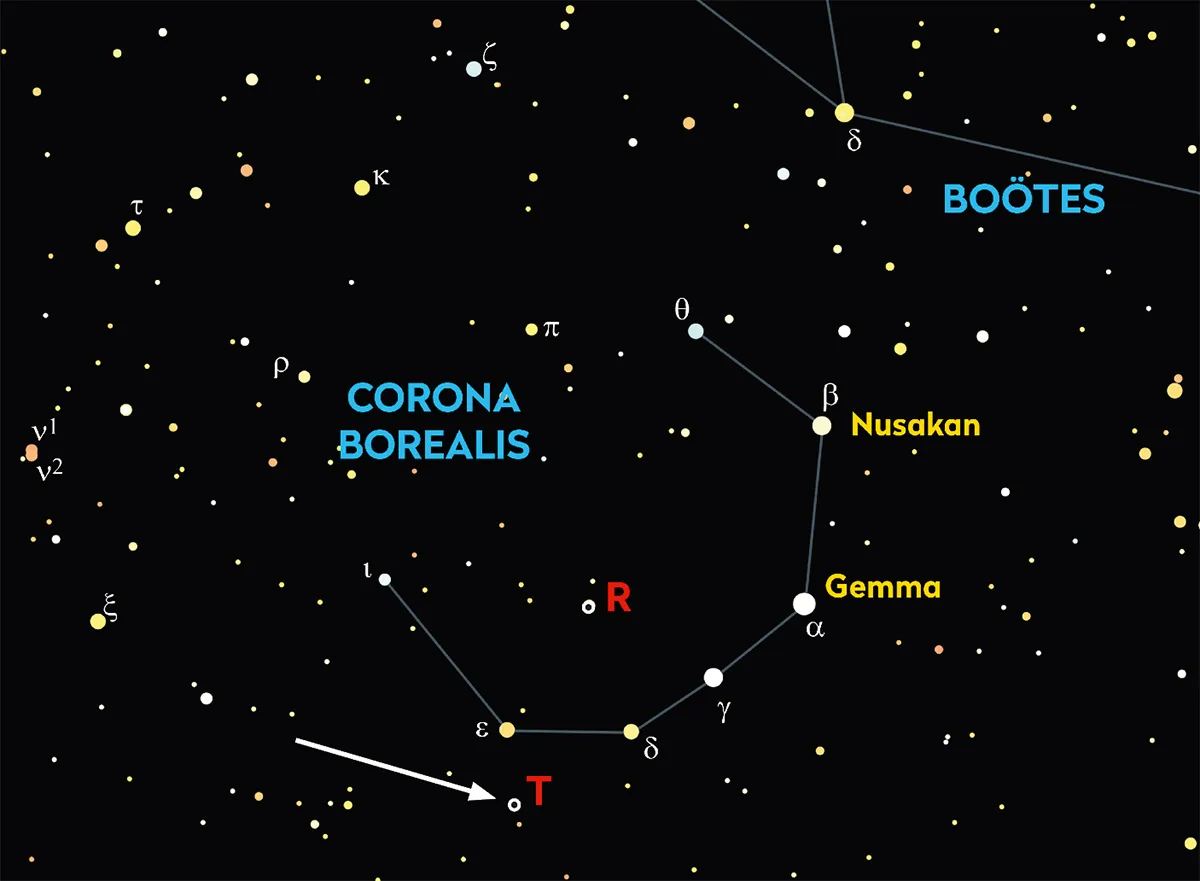

T CrB, visible in the constellation Corona Borealis, occurs roughly every 80 years, which is useful to know if you're an astronomer searching for historic records of it in astronomical archives.

Bradley E. Schaefer of Louisiana State University believes he's found evidence that the T Coronae Borealis nova was observed and recorded in 1217 by Abbott Burchard of Ursberg Abbey.

The paper stating the find can be found at arxiv.org (link at the bottom of this page) and also contains information about a sighting in 1787.

"T CrB has a recurrence timescale near 80 years," Schaefer says.

"So it is reasonable to look backwards in time for prior eruptions, around 1786, and so on back. I have investigated two long-lost suggestions that T CrB was seen in eruption in the years 1217 and 1787."

The 1787 sighting

In the paper, Schaefer points to a catalogue published in 1789 by the Reverend Francis Wollaston, an astronomer and clergyman.

Wollaston's catalogue, Schaefer says, "reports an astrometric position for a star that is exactly on top of T CrB."

Astrometry is a branch of astronomy concerned with measuring the positions and movements of stars in the sky.

Wollaston's letters reveal that observations were made on at least four occassions with both a large and small telescope, around Christmastime and up to 28 December 1787.

"Wollaston's limiting magnitude for his astrometry is near +7.8 mag, so T CrB would have to have been in eruption," Schaefer says.

"With other transients strongly rejected, the only way that Wollaston could get the coordinates was to have measured the coordinates of T CrB itself during an eruption."

The 1217 sighting

In the Ursperger Chronicle of 1225, Abbott Burchard of Ursberg Abbey writes about observations made in 1217, which could show that he too witnessed the T Coronae Borealis nova.

If true, this would be the oldest recorded observation of the nova, and not dissimilar to records that show the Crab Nebula was observed and recorded by Chinese astronomers in 1054.

Schaefer reveals how Burchard describes a transient star that was visible for many days in autumn of 1217 in the constellation of 'Ariadne's Crown', which is Corona Borealis.

"A bright transient lasting for 'many days' can only be a nova, a comet, or a supernova," Schaefer says.

"Burchard's event cannot be a supernova or some different nova, due to the lack of any bright remnant.

"The object cannot be a comet because Burchard explicitly called it 'stella' (i.e. a point source) instead of any of the several medieval German terms for comet.

"Further, Burchard labeled it as a 'wonderful sign' with very positive connotations, whereas comets are universally regarded as amongst the most evil and dangerous omens in the sky."

Given what we know about T CrB's 80-year occurrence, this could be 'mystery solved'.

Was what Abbott Burchard saw in the night sky the nova event we know as T Coronae Borealis?

It seems incredibly likely that it was, writes Schaefer.

"The reported event is just as expected for a prior eruption of T CrB, and all other possibilities are strongly rejected, so the case for the 1217 eruption of T CrB is strong."

Read the paper at arxiv.org/abs/2308.13668