The December night sky can be truly stunning, with dark skies and beautiful stars, clusters and galaxies galore.

As the countdown to Christmas begins, we bring you glad tidings.

We’re giving you 22 different, glorious celestial sights to see with your naked eye, binoculars and a telescope in the run-up to Christmas.

New to stargazing? Read our guide to astronomy for beginners.

So cross your fingers for good weather, because after you’ve dumped your shopping bags, and grabbed a cuppa and a mince pie, you can wrap up warm and head outside to enjoy a winter wonderland of bright planets, beautiful constellations and sparkling star clusters.

For more advice, read our guides on the best winter constellations and our 12 astronomy sights for Christmas, or find out what's in the night sky on Christmas Day.

Stargazing advice

There are a few general pieces of advice you can follow that will help make your stargazing or astronomy session even more enjoyable.

Stay clear of light pollution if you can and allow 30 minutes for your eyes to adapt to the dark: you really will see more!

Use a red torch to find your way and turn your smartphone screen red if you want to consult an astronomy app, as this will help preserve your night vision.

Each target is visible throughout December 2023, so if one night is cloudy, just pick the next clear night and find a few of them.

Below is our pick of the best targets to see in the night sky in December, with some handy star charts to help you locate each one.

Merry Christmas everyone. Let’s get started!

25 night-sky sights for December 2023

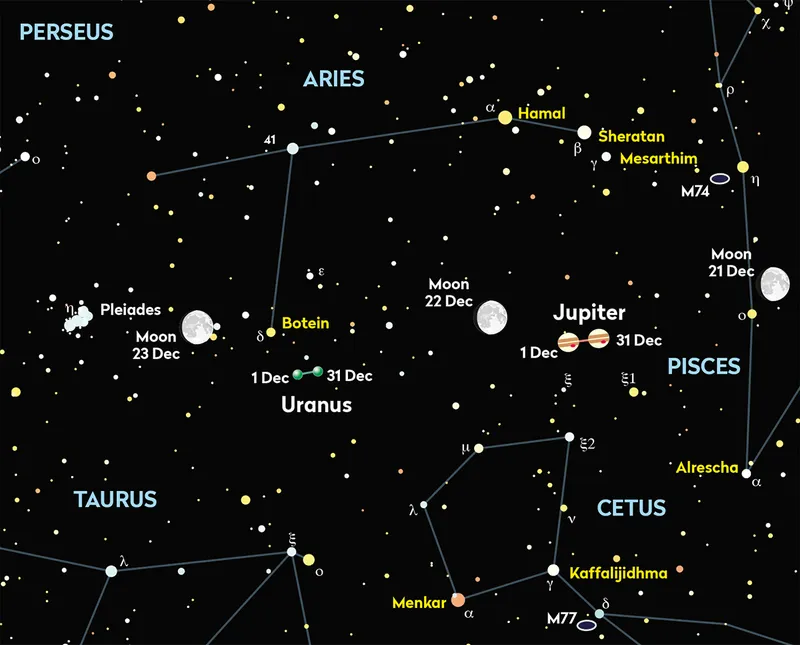

Uranus

See it with: A large telescope

Uranus is well placed in the December 2023 night sky, having reached opposition in the middle of November. It will be good throughout the month, and you can find it in the constellation Aries.

Uranus is shining at mag. +5.6 and located less than 3° south of mag. +4.3 Botein (Delta (δ) Arietis).

Find it using our chart above.

For more info, read our guide to Uranus

Jupiter

See it with: Binoculars and a small telescope

Half an hour after sunset on December evenings, look to the southeast and you’ll see a bright blue-white ‘star’ shining above the skyline, obvious to the naked eye at mag. –2.4.

This is Jupiter, the largest planet in our Solar System.

With binoculars you’ll be able to see up to four of its family of 80+ moons - the large Galilean moons - and a telescope will show horizontal bands of toffee- and coffee-hued cloud on its slightly flattened creamy disc.

For more info, read our guide to Jupiter

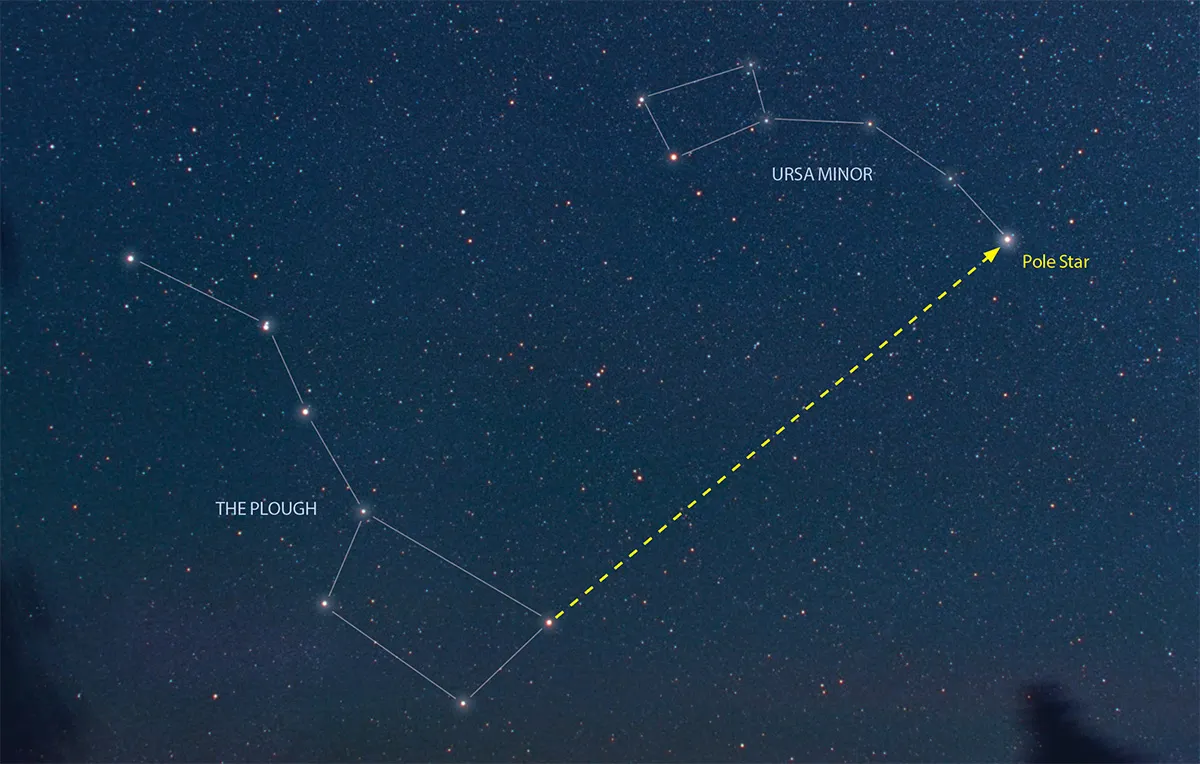

The Plough

See it with: The naked eye

One of the most famous night-sky sights of all, The Plough isn’t actually a constellation but an asterism, a small pattern of stars obvious to the naked eye.

The Plough is part of the constellation Ursa Major. As darkness falls on December evenings, it looks a lot like a question mark of stars low in the north night sky.

For more info, read our guide on how to photograph a constellation

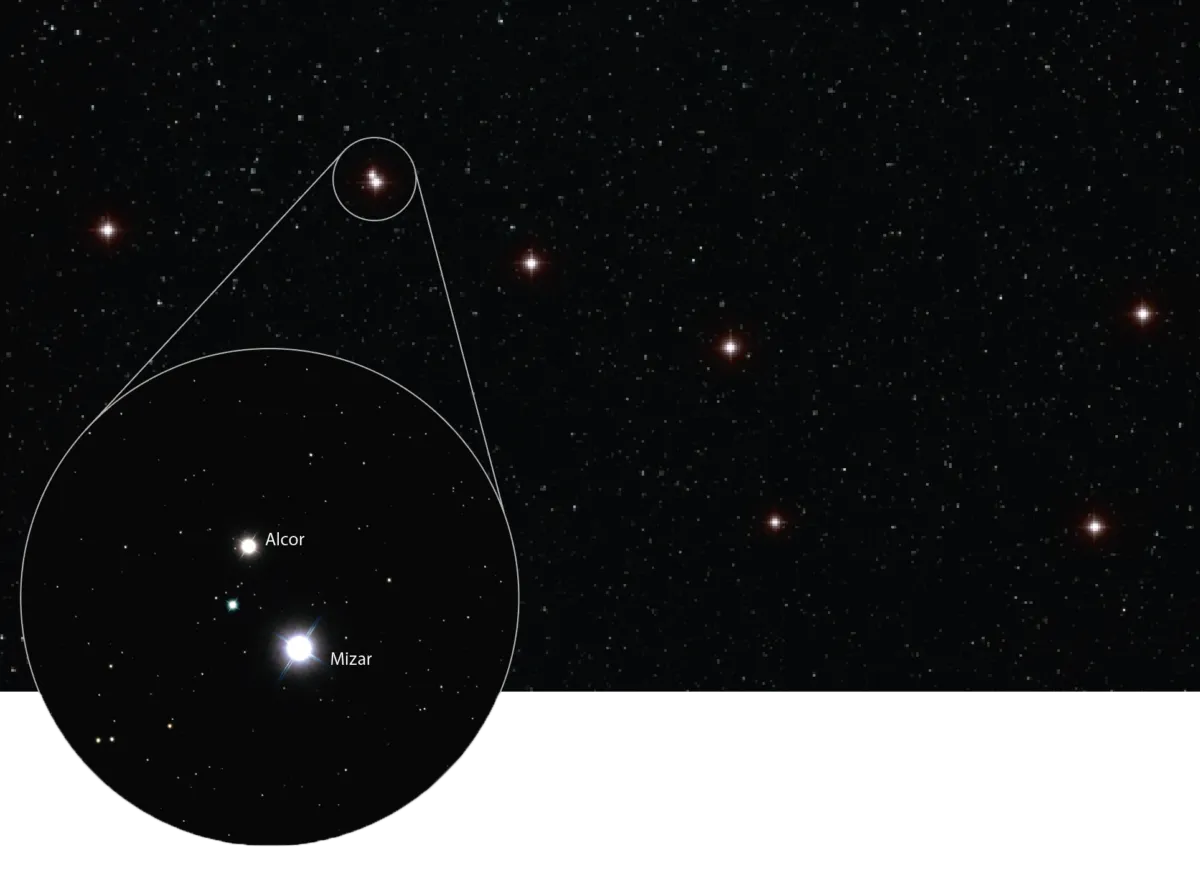

Mizar/Alcor

See it with: Binoculars

This double star can be found in the centre of the Plough’s handle.

You may be able to split the pair with your naked eye, but if not then a pair of binoculars or a small telescope will give you very crisp views.

Mizar, the brighter of the two, shines at second magnitude, while fainter Alcor has a brightness of mag. +4. ο.

For more info, read our guide to Mizar and Alcor

Polaris

See it with: The naked eye

Many think that Polaris, aka The Pole Star, is the brightest star in the sky, but at mag. +1.97, it is only the 48th brightest.

However, it is perhaps the most important star in the northern sky because it is almost directly above Earth’s north polar axis, and as our planet spins all the stars appear to wheel around it while it seems to remain stationary.

For help locating it, read our guide on how to find the North Star.

For more info, read our guide toPolaris

Double Cluster

See it with: A small telescope

Located roughly halfway between the ‘W’ of Cassiopeia and the inverted ‘Y’ of Perseus, this pair of star clusters, so close together they are almost touching, is a favourite of many amateur astronomers.

Visible as a smudge to the naked eye, binoculars and small telescopes reveal two clusters of pinprick stars, looking like piles of salt spilled on a black tabletop.

For more info, read our guide to the Double Cluster

Cassiopeia

See it with: The naked eye and binoculars

This small constellation is an unmistakeable highlight of the northern December night sky.

If you face south after dark and tilt your head right back, almost directly overhead you’ll see a ‘W’ of silvery-white stars all of roughly the same brightness.

Because Cassiopeia is embedded in the Milky Way, if you sweep your binoculars around it you will see countless thousands of fainter stars.

For more info, read our guide to Cassiopeia

Caroline’s Rose

See it with: A small telescope

Caroline’s Rose is an open cluster in Cassiopeia named in honour of astronomer Caroline Herschel, sister of William Herschel.

Around 8,000 lightyears away, its flowery name comes from its loops and curls of orange and blue stars that form the shape of rose petals when viewed through a telescope.

For more info, read our guide to Caroline's Rose

The Andromeda Galaxy

See it with: The naked eye and a small telescope

To the naked eye M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, is an elongated smudge below Cassiopeia visible in the December night sky.

Through binoculars or a small telescope you will see it is a beautiful, lens-shaped patch of misty light much larger than the full Moon, with a noticeably brighter centre.

A giant spiral galaxy, bigger than our own Milky Way, it is 2.2 million lightyears away – the most distant object visible to the naked eye.

For more info, read our guide to observing the Andromeda Galaxy

The Triangulum Galaxy

See it with: A small telescope

Although not as large in the sky as its near neighbour M31, and a lot fainter too (mag. +5.8 vs mag. +3), M33, the Triangulum Galaxy, can just about be seen with the naked eye on nights of good seeing under skies free of light pollution.

Through binoculars and telescopes this face-on spiral galaxy looks like a small, round smear. Larger telescopes and long-exposure photos reveal its beautifully curved spiral arms, mottled with star clouds.

For more info, read our guide to the Triangulum Galaxy

M15

See it with: A small telescope

Globular clusters are huge balls of many thousands of stars and 6th-magnitude M15 is among the brightest and most observed globulars in the December night sky.

It is 175 lightyears across but 34,000 lightyears away, so it looks like an out-of-focus star to the naked eye and a round smudge in binoculars.

With a telescope it is a much more impressive, tightly-packed cluster of silvery-grey stars.

For more info, read our guide to globular clusters

Vega

See it with: The naked eye

One of the three strikingly bright stars that make up the famous Summer Triangle asterism, Vega is still clearly visible in the December night sky over the festive period.

At mag. +0.03, Vega is the fifth-brightest star in the whole sky. You’ll find it shining low in the west as the sky grows dark, a beautiful blue-white spark of light.

By midnight it will be almost scraping the horizon, but then it will start to climb higher again, never quite setting.

For more info, read our guide to Vega

The Ring Nebula

See it with: A small telescope

Just under 7° away from Vega, planetary nebula M57 is famously known as the Ring Nebula because of its smoky, ring-like appearance through a telescope.

Planetary nebulae are the results of dying stars puffing off their outer layers, and while there are larger examples elsewhere in the sky, M57 is greatly loved for its beautiful colours.

It looks like an out-of-focus green star through binoculars.

For more info, read our guide to the Ring Nebula

Orion

See it with: A small telescope

Considered by many to be the most handsome and dramatic constellation

in the night sky, Orion, The Hunter’s starry hourglass dominates the view throughout December.

By 8pm all its brightly-coloured stars are clear of the horizon, shining like jewels low in the east.

Ruddy mag. +0.6 Betelgeuse and fierce blue-white mag. +0.3 Rigel shine diagonally opposite each other, on either side of the famous Belt.

For more info, read our guide to the Orion constellation

Orion’s Belt

See it with: Binoculars

This diagonal line of three icy stars pulled tightly around Orion’s waist is one of the most famous asterisms in the sky and a striking sight as they rise above the horizon on frosty December nights.

The three are all around second magnitude (as bright as Polaris). Through binoculars you’ll see many fainter stars shining around them.

For more info, read our guide to Orion's Belt and Sword

Orion Nebula

See it with: A small telescope

There are many bright nebulae in the sky, but the Orion Nebula, M42, is in a class of its own.

Glowing in the centre of Orion’s Sword, which hangs down from the left side of the Belt, the nebula is a ghostly patch to the naked eye.

Binoculars show it as a feathered, grey smudge, while telescopes reveal it to be a beautiful cloud of grey-green light, with dark notches and streamers silhouetted across it.

For more info, read our guide to the Orion Nebula

Sirius

See it with: The naked eye

The brightest star in the sky, Sirius blazes to the lower left of Orion.

Because it never rises very high in the sky from mid-latitudes like the UK, it is always seen through the turbulent air above the horizon and so appears to flash and scintillate dramatically through the long winter nights, glinting like a finely-cut diamond.

Seen through a telescope in the December night sky it is literally a dazzling sight.

M41

See it with: Binoculars

Lying only 4° south of brilliant Sirius, this mag. +4.5 open star cluster is often overlooked, but it is as lovely a sight as many better-known clusters.

Around 100 stars can be seen with the naked eye and it is very pretty through binoculars.

For more info, read our guide to open star clusters

The Beehive Cluster

See it with: Binoculars and a small telescope

Also known as the Beehive Cluster, M44 is not high in the December night sky until after 10pm, but it is worth waiting for.

Very obvious to the naked eye as a large smudge of stars in the centre of Cancer, at only 577 lightyears away M44 is one of the nearest star clusters to us.

It contains around 1,000 stars, hundreds of which can be seen through binoculars or a small telescope.

For more info, read our guide to the Beehive Cluster

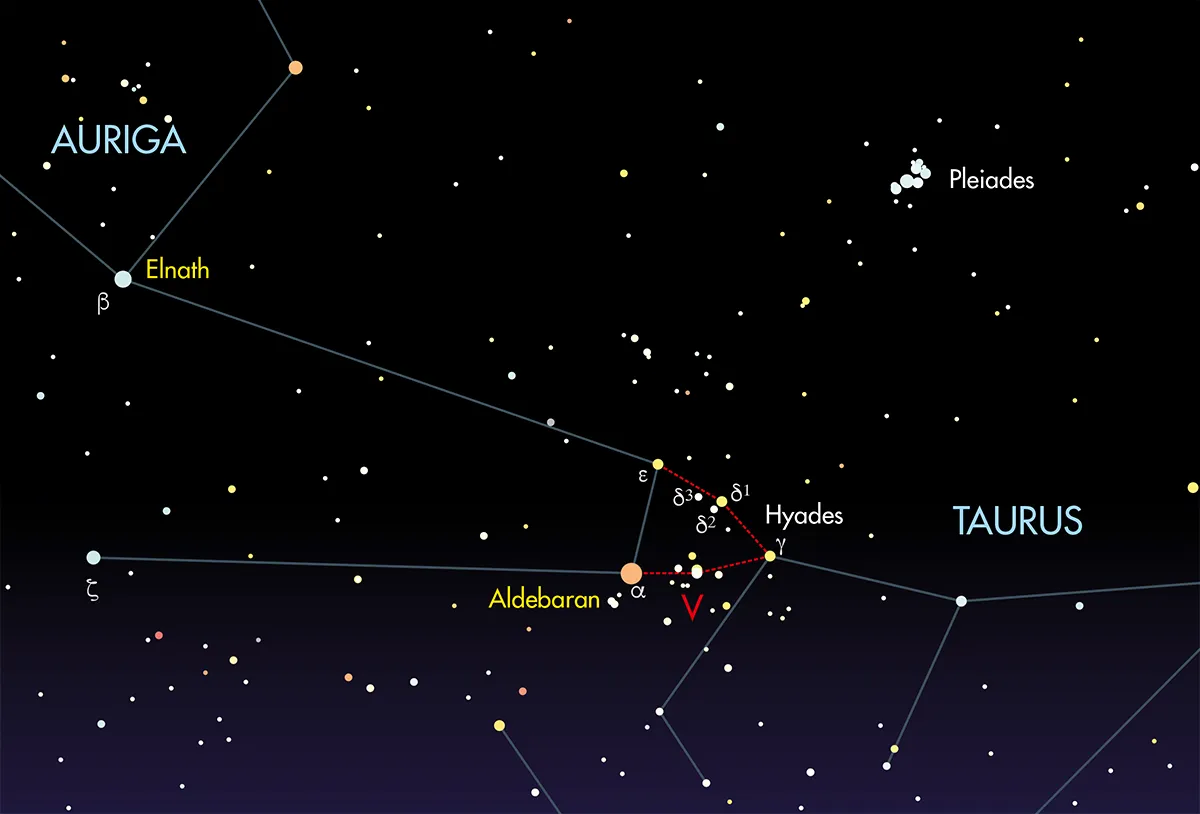

The Hyades

See it with: Binoculars and a small telescope

Representing the sharp horns of Taurus, the Bull, this V-shaped star cluster is obvious to the naked eye to the upper right of Orion.

Lying on its side like a mathematical ‘greater than’ symbol, the Hyades contains several hundred stars.

Its brightest star, the orange-hued Aldebaran, is not actually part of the cluster; it just happens to lie in the same direction as seen from Earth.

For more info, read our guide to the Hyades open cluster

The Pleiades

See it with: Binoculars and a small telescope

Many observers believe the Pleiades, M45, is the most beautiful star cluster in the sky. It's certainly one of the most beautiful in the December night sky.

To the unaided eye it is an eye-catching knot of seven blue-white stars – hence its popular nickname ‘The Seven Sisters’.

Binoculars reveal dozens more stars dotted around the seven brightest, and through a telescope the Pleiades is a spectacular spray of stars: so many that they spill out over the edge of even a low-power eyepiece’s field of view.

See if you can pick out star Electra.

For more info, read our guide to the Pleiades and how to photograph the Pleiades.

Aldebaran

See it with: The naked eye

Rising in the east early on Christmas Eve night and throughout the December night sky is the red giant star Aldebaran. It’s found in Taurus and is known as the ‘red eye of the bull’.

The star appears to be in the Hyades cluster but is actually much closer to Earth. Find it by extending the line of Orion’s three Belt stars up and to the right.

Aldebaran is also part of the Winter Hexagon asterism: it’s a great jumping-off point to star-hop to some wonderful widefield targets.

For more info, read our guide to Aldebaran

This guide originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.