The aurora is one of nature’s most beautiful spectacles, but also one of the most elusive, although at times of solar maximum the chances of spotting a display are vastly increased, as we saw most recently during the 10 May 2024 aurora display.

There are no guarantees when it comes to seeing the aurora, but you might be able to stack the odds in your favour.

Learn how to photograph the Sun

- Sign up for our latest online series, The Art of Solar Imaging, beginning April 2025

The next few years are going to be some of the best for those hoping to catch the aurora, as our Sun is currently approaching a time of intense activity, known as solar maximum.

To understand why, we must travel to the aurorae’s beginnings on the surface of the Sun.

What causes aurora

Our star emits a constant stream of charged particles, known as the solar wind, that traverses through the Solar System at huge speeds.

This wind then eventually collides with our planet, or rather the protective bubble created by Earth’s magnetic field around the planet, known as the magnetosphere.

Magnetic fields can skew the path of charged particles, changing their motions so that they move along its field lines.

As such, the solar wind is deflected around the magnetosphere so that most of it passes safely around the outside, like water flowing past a rock in a stream.

Some of the particles, however, are able to sneak through into our magnetosphere.

Once inside, they become caught in field lines that guide them down towards the planet.

These solar particles, along with others that were previously trapped within our planet’s radiation belts, are then accelerated down towards the surface by Earth’s magnetic field.

Forming a ring around the north and south poles, known as the auroral oval, the particles keep travelling until they hit molecules in Earth’s atmosphere.

This transfers some of the accelerated particles’ energy, causing the atmospheric molecules to glow.

The altitude and the type of molecules they hit determine the colour of the glow.

The aurorae’s famous green hues come from oxygen molecules at an altitude of 100–240km.

The less common reds originate from oxygen above 240km, while the rarely seen blues are created by nitrogen under 100km.

When a flurry of charged particles bombard the atmosphere at once, the glow is great enough for human eyes to pick up.

This is when the aurorae dance before our eyes.

Aurora, solar cycle and solar maximum

Precisely how aurorae work is still being discovered, but one thing that’s clear is that the more active the Sun is, the more likely it is that spectacular aurorae will arise.

Not only that, but if the solar wind is blowing faster, the more energy the particles have.

This makes the auroral oval larger, pushing it closer to the equator, meaning the lights can be seen over a much larger area.

For this reason, dedicated aurora hunters watch for times when the Sun is more active.

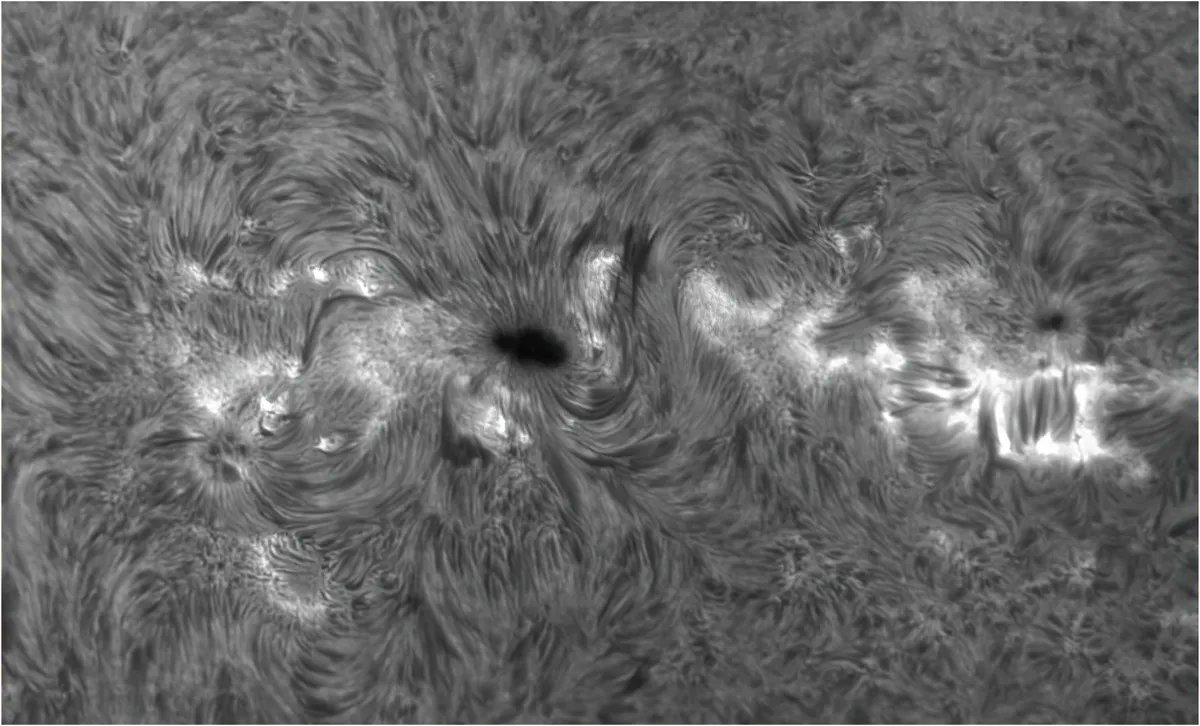

One event to particularly keep an eye on are coronal mass ejections (CMEs), where the Sun’s twisting magnetic field flings a blob of its own stellar material out into space.

It’s possible to get some warning that a CME is about to collide with Earth, thanks to NASA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), which monitors the Sun’s activity in real time, looking for the solar flares that usually herald an incoming CME.

Currently, however, there’s no way to predict when a CME is going to erupt.

It is, however, possible to say when it’s more likely for such events to occur.

This image was captured by NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory on 4 January 2002. Credit: NASA/SOHO

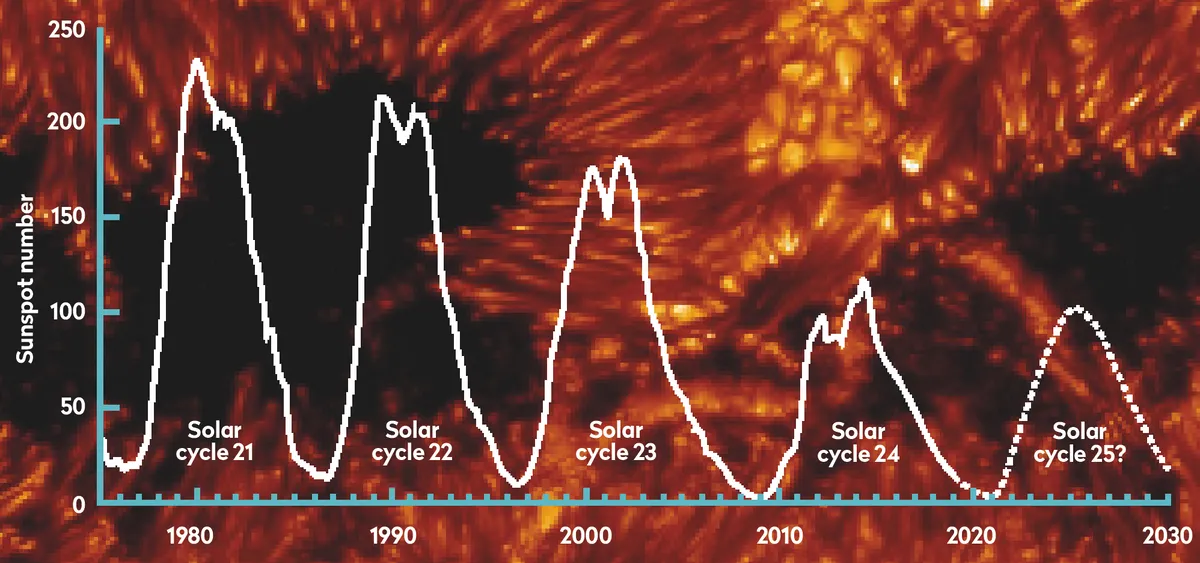

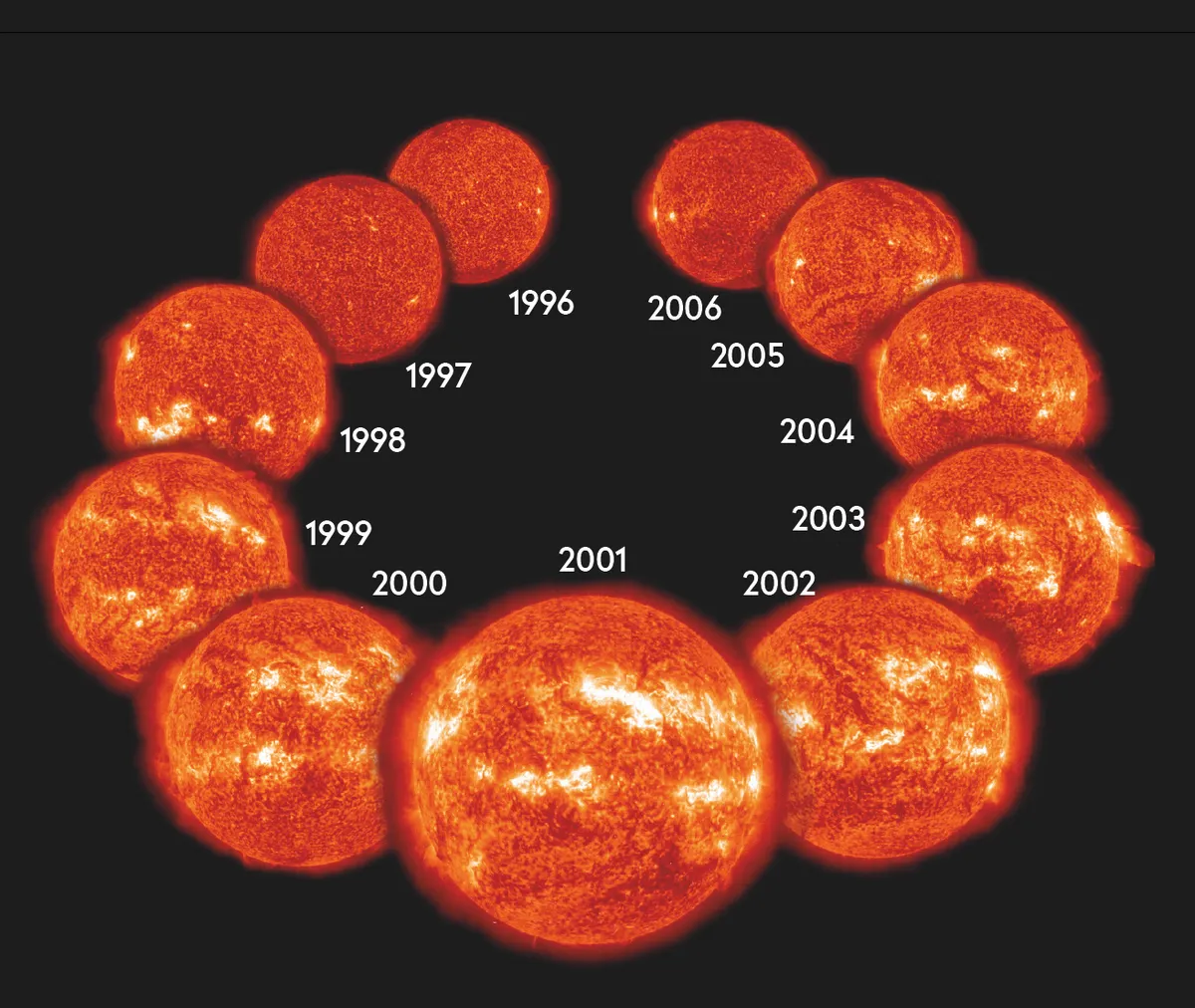

The Sun goes through an approximate 11-year sequence of rising and falling activity, known as the solar cycle, which solar scientists track by measuring the number of sunspots on the solar surface.

Each cycle begins with a solar minimum; at these times it could be months, or even years between one sunspot and the next.

Then, over several years the number of sunspots increases until they reach a peak, known as the solar maximum.

After this, the sunspot numbers trail off once more to a new minimum and the start of a new cycle.

Peak solar cycle?

Though the cycle tracks sunspots, the rise and fall of other activity of the Sun follows alongside, including CMEs, which usually reach a peak in the years just after solar maximum.

We are currently in Solar Cycle 25, which started in December 2019, so-named because it is the 25th since records began.

Initial predictions put the maximum in mid 2025 and forecast that it would be one of the weakest cycles, with low sunspot numbers.

As the cycle has gone on, however, it’s quickly become clear that those predictions were not correct.

Equipment: ZWO ASI178MM camera, Lunt 60mm H-Alpha telescope, double-stack 50mm filter, B1200 blocking filter, Sky-Watcher AZ-EQ6 Pro mount

The actual number of sunspots is much higher than forecast, and the date of solar maximum has now been revised to sometime between January and October 2024.

That means it could be the peak of solar activity right now, although we won’t know for sure exactly when the peak occurs until after it has passed and activity begins to fall again.

We won’t know exactly how active Solar Cycle 25 will be until then, but it’s already shaping up to have a higher peak than the previous solar cycle, Solar Cycle 24.

And it’s already begun to show in the aurorae. In 2023, there were 13 X-class solar flares – the most powerful of their kind – several of which were accompanied by CMEs.

The Northern Lights were seen as far south as West Wales and Cornwall in the UK, while a photographer was able to capture them over Death Valley, California in the US.

Meanwhile, their Southern Hemisphere counterparts, the Southern Lights, have been making rare appearances above mainland Australia and New Zealand.

Getting to witness an aurora display always involves an element of chance.

But if you’ve always wanted to get out and see the Northern Lights dance across the night sky, the next few years will definitely give you the best chance of catching the show.

Shapes of the aurora explained

Curtains

Created from rays of light moving together in bands, viewed from a distance these sweeping forms resemble a set of hanging curtains.

Bands

Similar to arcs, bands tend to have a more undulating appearance to their lower border, creating a snaking glow across the sky.

Patches

More diffuse than other displays, these blobs of light tend to spread out across the sky.

Rays

These shafts of light stretch upwards into the sky and during more active displays can even appear to pulse and move.

Coronae

Meaning crown, coronae are large starburst formations. They can be difficult to catch, however, as you’ll only see such a view if you’re directly underneath it.

Arcs

Many displays begin as a curve of bright light across the sky, known as an arc, before transforming into more complex shapes.

How to predict an aurora display

Aurora displays can show up at any time after dark, but there are definitely times when an aurora sighting is more likely, whether it’s near solar maximum or not.

As aurorae are most visible against dark skies, it’s best to hunt for them in spring, autumn and winter, when the nights are longer.

For an even better chance, stick to the months around the equinoxes: March and April, September and October.

During this time, Earth’s magnetic field is best orientated to the solar wind, and more likely to create the interactions needed to produce the lights.

The best place to see the Northern Lights is in the auroral oval.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the oval sits at a latitude around 65°N to 70°N, covering the northern regions of Finland, Sweden, Norway and Canada, as well as Iceland and Alaska.

These are all popular sites for aurora hunters.

Those located a little further south would do well to keep an eye on aurorae forecasting apps and websites, however, to see if a particularly energetic CME is on its way.

This can push the oval to more southerly latitudes and it’s not uncommon for the lights to appear above Scotland.

A particularly strong solar storm will move the oval even further south than that.

Whether you’ve travelled to see the aurorae or they have come to you, the faint lights are best viewed from a dark site as far away from light pollution as possible.

They can appear at any time, but the best views are usually between 10pm and 2am.

Once you’re in position, it’s just a case of watching and waiting for the lights to begin forming on the sky.

Find out more in our guide on how to predict an aurora display.

This article appeared in the March 2024 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine