The question has often been asked: "Which is the best season of the year for astronomical observing – spring, summer, autumn or winter?"

This sounds like quite a simple question to answer but it isn’t. There are so many factors to be taken into account, when trying to decide the best time to go stargazing or when to observe planets or deep-sky objects through your telescope.

In some countries, of course, things are much easier because you can have a very good idea of what the weather is going to do.

Read our guide to the best constellations, season-by-season

Even so, there can be disappointments. I remember that years ago I was at Port Elizabeth, in South Africa, where there is a good observatory.

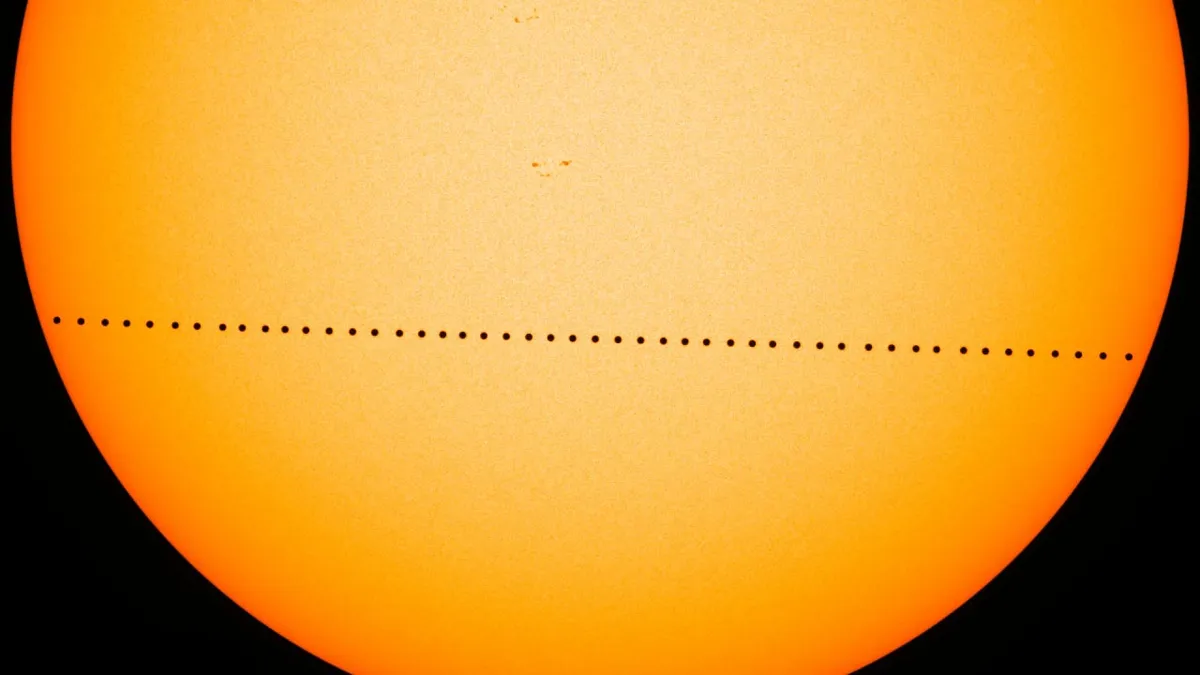

A transit of Mercury was due and I had never seen one before. At that time of the year Port Elizabeth always has clear skies. I was there for six weeks and during that time there was one cloudy day – the day of the transit.

Of course, our weather in the British Isles is quite unpredictable.

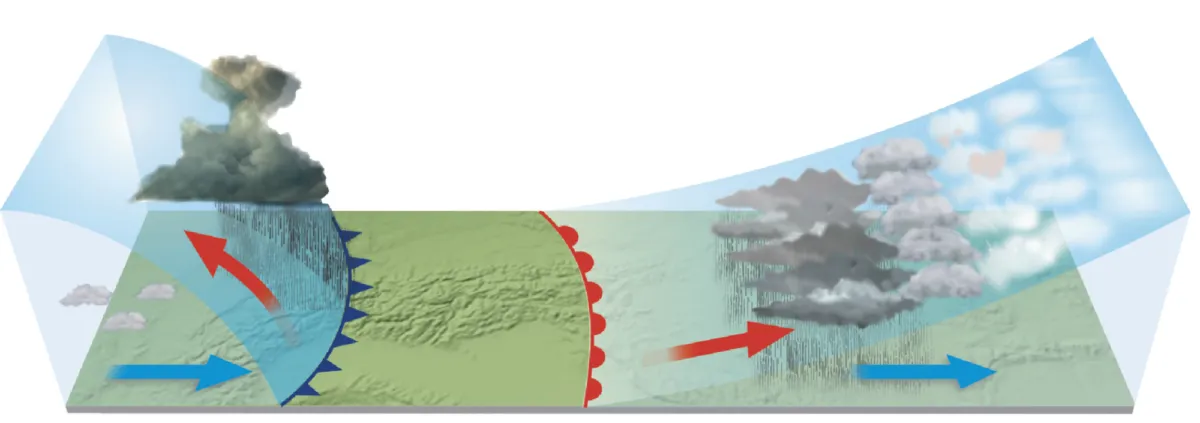

Some areas have more cloud and rain than others. But when it comes to the weather nothing can ever be planned and there is very little that the observer can do about it.

Moreover, we have to put up with the ever-increasing menace of light pollution.

Light pollution

Anyone who lives in a city or large town will never see the Milky Way and telescopically will probably have to confine themselves to studying the Sun – unless they have a good portable travel telescope.

Things on this front are better than they used to be as some really good telescopes are small enough and light enough to fit into a car.

Even so, the sky is always polluted to some extent when the electricity is on.

I remember one occasion when a power cut blacked out the whole of the south of England.

For several hours the sky was inky black and I could see stars that were normally too faint for me to see without optical aid.

There was, of course, a snag. I made haste to my observatory and opened the dome, expecting to enjoy myself – but I had forgotten that the drive of my 15-inch reflector was electric.

Muttering things that I will not write down here, I closed the dome and waited patiently for the power.

A word on astronomical seeing

My home is in Selsey, near the tip of the Bill; I am only just out of spray range.

In fact this area has a sort of microclimate and is generally a degree or two warmer than most other places, with less rain.

This includes the Bill, Bognor Regis and a slice of the coast of the Isle of Wight (which is why King George V went to Bognor to recover and made that unfortunate remark about it).

My main interest is with the Moon and planets, and my ideal is a very steady atmosphere.

I do not in the least mind a bit of mist; it calms the air down. Over the years I have found that mist can most often give me a spell with seeing at Antoniadi I.

The Antoniadi scale gives five grades of seeing, from I (well nigh perfect) down to V (so poor that observing would probably not be attempted except for some special purposes, such as an occultation).

A glorious sky, with stars blazing down and twinkling strongly, may be useless from my point of view – but certainly not to deep-sky enthusiasts, such as nova hunters.

We depend upon our chosen targets being available and there are dead periods; for instance Mars is virtually out of view for long periods and we lose the Moon for part of each month – to the joy, I admit, of the nova hunters!

But there are always plenty of stars around.

Stargazing in summer

Summer has its advantages but there are fewer hours of darkness and at full Moon, or a night or two either side, there is no real darkness at all.

I am speaking about Selsey, however, and naturally I realise the situation is different elsewhere: north Scotland, for example.

I am not too bothered, because the planets at least are often well seen with steady air and a lightish sky.

Catch Mars at dusk or dawn and the image can often be really good.

Stellar observers cannot operate properly under these conditions and they positively hate the Moon, which is understandable!

For me, summer nights are very variable but every now and then we do have a succession of exceptionally clear ‘astrometric’ nights.

Stargazing in winter

There is plenty of darkness in winter, with cold, transparent nights.

I used to go out and open my dome but sometimes I knew from the outset that I was in trouble. Twinkling was the clue.

If Sirius flashed violently in various colours, the image was bound to be unsteady.

And if Capella also twinkled strongly from near the zenith, I prepared for seeing of Antoniadi III or worse.

But a night of this sort would be good for concentrating on dim variable stars.

Stargazing in spring

Spring can be favourable – though spring 2006 was atrocious in Selsey, and if Selsey has cloud, most other places are likely to have more cloud.

(Yes, I know we had a couple of tornadoes but I assure you these were atypical).

Over many years, I have found that in this part of Sussex, October is probably the best month for observing the night sky. I would be interested to know what others think.

The only thing we can do is to make the most of our opportunities.

And in a way I suppose we are lucky. I remember talking to an astronomer at what was then Leningrad, now St Petersburg, where there is a very famous observatory, Pulkova.

"We haven’t had good conditions here," he said mournfully.

"We really have to keep to April and September. Near midsummer it never gets dark and in winter it’s always overcast."

And then, talking to an astronomer in Singapore, practically on the equator, where it is fun to look up after dark and see the Great Bear on one side of the sky and the Southern Cross on the other.

"Seasons?" he said with a chuckle. "Well, we really don’t have any." I’m not sure whether I was envious or not.

This article originally appeared in the July 2006 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.