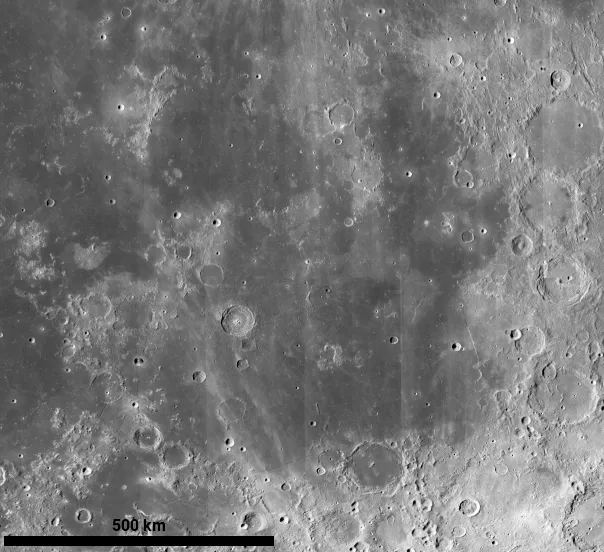

Deslandres is a large, ancient and time-worn feature located just to the southeast of 750km Mare Nubium (the Sea of Clouds).

A day after the first quarter Moon, there are two extremes visible in this region: the young, bright 86km crater Tycho and the dark, lava-filled 98km crater Pitatus on the southern edge of Mare Nubium.

Centre to centre, Pitatus lies 410km north of Tycho.

Head three-quarters of the way along this connecting line starting from Tycho, then head east for 200km and you’ll be at the centre of Deslandres.

Quick facts

- Type: Walled plain

- Size: 235km

- Longitude/latitude: 5.6° W, 32.5° S

- Age: Older than 3.9 billion years

- Best time to see: First quarter or six days after full Moon

- Minimum equipment: 10x binoculars

What Deslandres looks like

Unlike either Tycho or Pitatus, Deslandres isn’t as well defined, appearing as a large rim containing flat yet battered terrain.

The most obvious rim is that which borders the northern portion of the crater, that to the south having been heavily bombarded and overlaid by smaller craters.

Amazingly, Deslandres is the third-largest crater formation on the Earth-facing side of the Moon.

Only 231km Clavius and 303km Billy are larger.

The roughly defined portions of Deslandres’s rim meant that for a long time it wasn’t recognised as a crater in its own right, until a suggestion by Eugene Antoniadi in 1942 led to official recognition by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1948.

Observing Deslandres

Deslandres is a wonderful feature to explore when the lunar terminator is nearby, thanks to the richness of smaller features that litter its floor.

The 33km crater Hell sits inside Deslandres close to the western rim.

Hell is well defined with a sharp rim that terraces down to a distinctive central mountain.

Many of the craterlets inside Deslandres are labelled as satellites of Hell, 21km Hell A further to the south of Hell, forming the right-angle in a right-angled east-pointing triangle with 14km Hell C.

Towards the northern internal edge of Deslandres’s rim is the flooded crater Hell B.

Those with larger instruments or high-resolution imaging setups may be able to see a crater chain running from just west of Hell A, past the western rim of Hell, heading straight north-northeast.

Another, much shorter chain can be seen 65km to the southeast of Hell B.

This consists of five small craterlets arranged in a straight line, heading north-northeast of 5km Hell H, marking the chain’s southern end.

The 41km crater Ball overlays Deslandres’s southwest rim, together with 29km Ball A to its northwest.

The weak southern rim of Deslandres to the east of Ball is pockmarked by small 10km craterlets before you arrive at a large southern rim interloper, the 63km partial crater Lexell.

Deslandres’s eastern limb fares no better, as it’s shared with 141km Walther. Perhaps 'shared' isn’t quite the right term here, as Walther is obviously the winner, the rim section here curved to better fit its overall profile.

Immediately west of Walther is 32km Walther W, a very rough-hewn feature that appears both elevated and flooded.

An 8km craterlet sits immediately west of Walther W which is labelled Walther G.

It and the much smaller 4km craterlet Hell Q mark the position of a young feature that appears very bright at the period around full Moon.

This feature was first mapped by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1672 and is occasionally referred to as ‘Cassini’s bright spot’.

Have you observed or photographed Deslandres? Get in touch and let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com