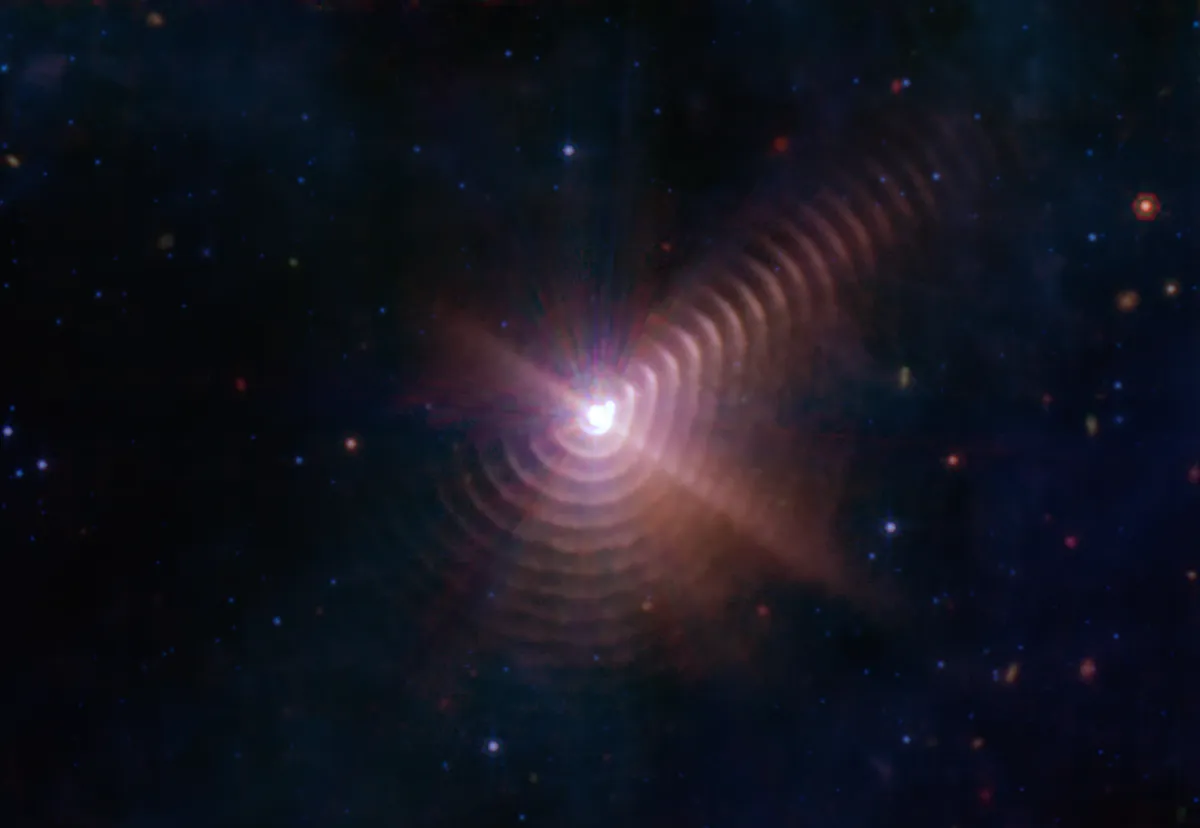

Binary stars, in which a pairs of stars orbit one another, might seem like science fiction, but they exist, and can be observed through telescopes.

Imagine if Earth orbited not one, but two stars, giving us two suns like Luke Skywalker's planet Tatooine in Star Wars.

If we took a journey back to when telescopes were first trained on stars, we'd witness an interesting discovery being made: not all stars we see as single points of light are in fact alone.

Some apparently single stars in the night sky are actually two stars; sometimes even more than two.

Double stars and multiple star systems are common, and you'll hear astronomers talking about 'splitting' or 'resolving' binary stars.

This means that, via the wonders of magnification and careful observation, they have managed to view the two stars as separate entities through their eyepiece.

Click here to read about WL 20, which JWST revealed to secretly be a pair of stars

Binary stars vs double stars - what's the difference?

As the number of double stars being found grew, it became necessary to divide the category up further to clarify exactly what sort of double star it was.

To understand the first category, optical doubles, imagine the true 3D nature of space with stars sprinkled all over the place.

From our viewpoint, one star may appear very close to another star, but this is only because the two stars happen to lie in the same direction from us in space.

In fact, these stars are not linked in any way.

One of them could be much further away from us than the other, but we have no way of knowing just by looking, because everything in the night sky appears as though it's the same distance away.

A good example of this is Albireo, which is not a true binary, but rather an optical binary. The two stars only appear close together.

- For basic stellar astrophotography, read our guide on how to photograph the stars.

Then there are the double stars that are linked by gravity. If you see one of these you’re looking at a binary star.

A good example for stargazers in the southern hemisphere sky is Zeta Reticuli.

It’s no coincidence that the stars of a double appear to be in the same place: they are both the same distance from us and orbit around each other.

It’s estimated that perhaps half of the stars in our Galaxy are binaries, although binaries account for only 5% of stars observed so far.

Unless your stargazing app or star atlas tells you so, simply by gazing at the sky there is no way of telling whether you’re looking at an optical double or a binary.

Only with the careful study of the movements in a double star can astronomers gauge whether the stars are gravitationally bound to each other or not.

What happens to stars in a binary system?

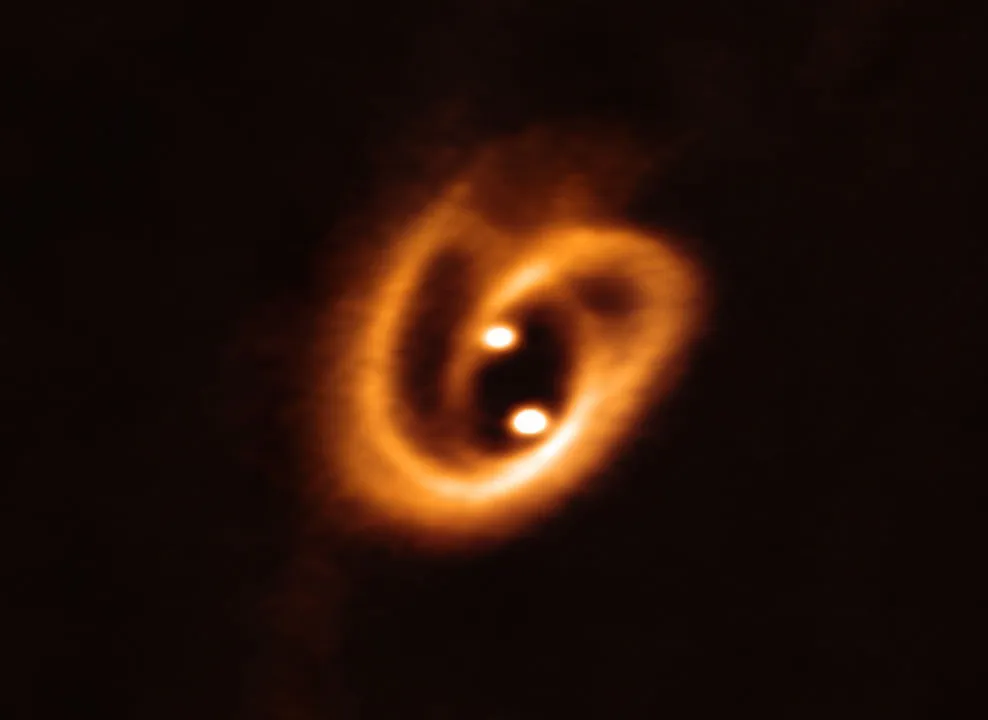

If you’re looking up at a binary star system, imagine what might be happening to the stars themselves.

Sometimes the stars in a binary system interact, especially when one is more massive than the other.

Gas can be pulled off the smaller companion, which can lead to tremendously destructive stellar explosions called supernovae.

You won’t see any of this going on when you look through a telescope, but double stars are amazing to observe, even for knowing this fact alone.

Some doubles show startling colour differences between the two stars, for example a shimmering yellow next to a vivid blue.

Binary stars that are yellow and blue might appear as though they are green stars, although a single star in itself won't actually be green.

With other double stars, the two will be more or less the same brightness, yet sit startlingly close together.

For more on this, read our guide to star colours.

Binary stars through a telescope

If you have a small, good quality telescope, say 4 inches in diameter, you should be able to see binary stars and double stars up to 1.15 arcseconds apart (if seeing conditions are perfect).

A star like Sabik, for example, can be quite tricky to resolve.

Our top five binary and double stars listed below should all be within your reach.

You can also use binary and double stars to test your telescope’s optics.

How well you can split the stars depends on the quality of your optics, as well as the size of your telescope’s aperture, or front lens.

To split double stars closer than 1.15 arcseconds apart, you're going to need a bigger telescope.

You can find out the closest binary and double stars a telescope will split by dividing 4.6 by the diameter of the telescope’s front lens in inches.

This is a theoretical calculation though, because if the atmosphere is fairly turbulent then you won’t be able to see the components of a really close double star.

Take a look at our five favourite binary and double stars and you’ll soon be hooked on these jewels of the night sky.

5 binary and double stars to spot in the night sky

Albireo

Constellation: Cygnus

Albireo is a lovely golden and blue double. The golden component is mag. +3.1, while the blue member is mag. +5.1. You’ll need a scope to see the pair.

Almach

Constellation: Andromeda

The third brightest star in Andromeda is Almach. It has a brighter yellow star of mag. +2.3 close to a mag. +5.1 greenish companion. To resolve them you’ll need to use a telescope.

The Double Double

Constellation: Lyra

Epsilon Lyrae is a naked eye double star where both yellowish stars have a similar brightness of around mag. +5.5. However, with a scope you’ll see that both parts have their own binary star. Its constellation Lyra is also the radiant of the annual Lyrid meteor shower.

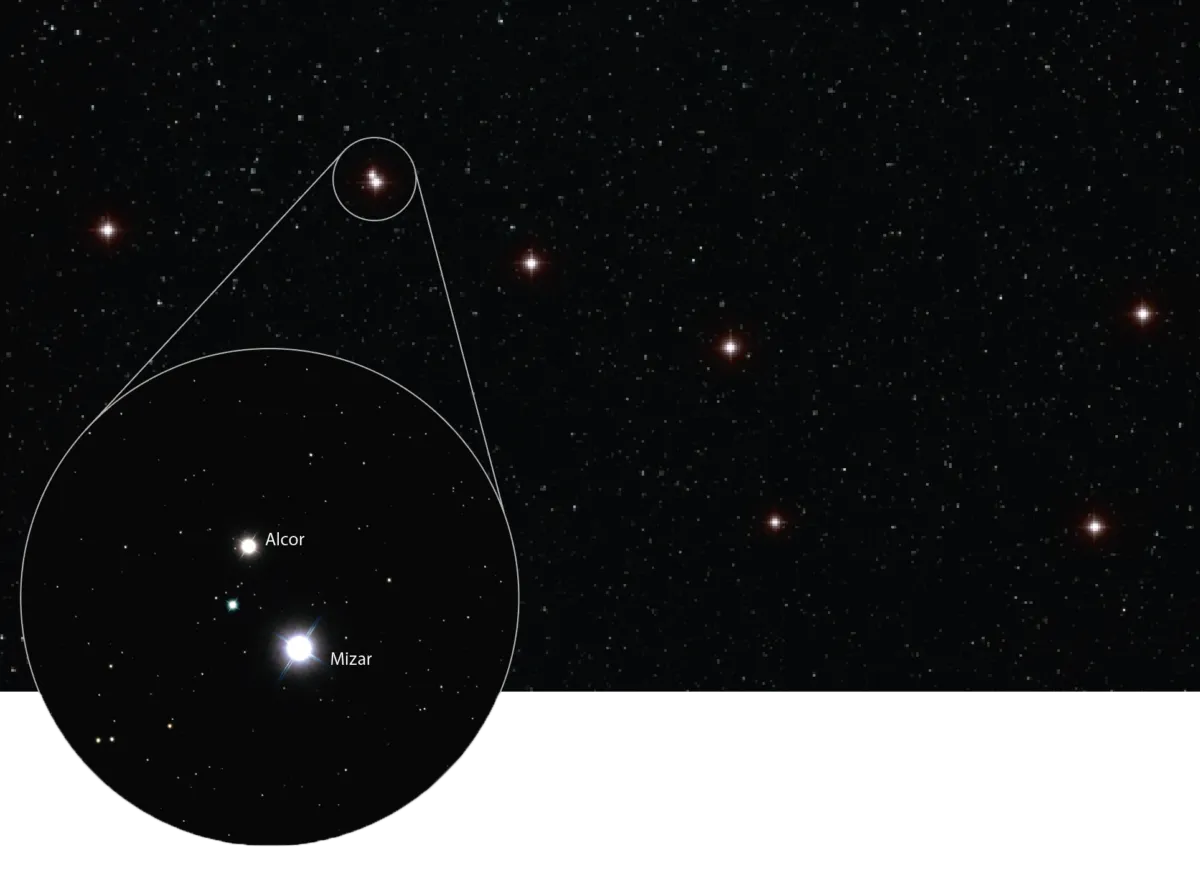

Mizar and Alcor

Constellation: Ursa Major

Mizar and Alcor, also known as Zeta and 80 Ursae Majoris are an optical double visible in the Plough asterism. The ability to see the two white stars, mags. +2.2 and +4.0 respectively, with the naked eye is a traditional test of good eyesight.

Phaeo and Phaesyla

Constellation: Taurus

This orange and white optical double is easily visible to the naked eye, with mags +3.8 and +3.4 respectively. Also called Theta Tauri, it is part of the Hyades star cluster.

What are your favourite binary stars and double stars? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

This guide originally appeared in the January 2009 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.