Have you ever considererd opting for lesser known astronomy targets, or indeed astrophotography targets?

It’s easy to go out on a rare clear night and set off on a tour of familiar objects with your telescope or astrophotography set-up.

It’s understandable – people want to make the most of any gaps in the clouds. But it could also be a wasted opportunity.

With the whole sky to explore, when the clouds clear shouldn’t you be looking for things you haven’t seen before?

After all, when you go on holiday you don’t just go into the same shops you have at home – you go exploring the backstreets and alleys, looking for unusual sights and experiences.

Here, we’re going to lure you off your beaten celestial track, swapping objects you've probably looked at again and again for 9 lesser-known astronomy and astrophotography targets.

Just check that each object is in the sky at the time you're observing and imaging.

Get more inspiration by signing up to receive the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter and listening to our weekly Star Diary podcast.

9 lesser known astronomy targets

Globular cluster M15

Instead of the Great Globular Cluster, M13

The most impressive globular cluster in the northern sky is generally accepted to be M13, the Great Globular Cluster in Hercules.

And it is indeed a stunning telescopic treat, but a short distance to its east, over on the opposite shore of the misty river of stars that is the Milky Way, lies another globular cluster that is well worth taking the time to find.

Close to one of the hooves of prancing Pegasus lies M15, a globular cluster with a magnitude of +6.2, which puts it just beyond the limits of naked-eye visibility.

Binoculars show it easily as a large, fuzzy star, and 6-inch or larger telescopes reveal its bright, smoky core and a mist of fainter stars around it.

With a diameter of 175 lightyears and a population of perhaps 350,000 stars, 13.2-billion-year-old M15 is one of the oldest globulars known.

So by all means have a look at M13 before it sinks behind the trees, but then find M15. You won’t be disappointed.

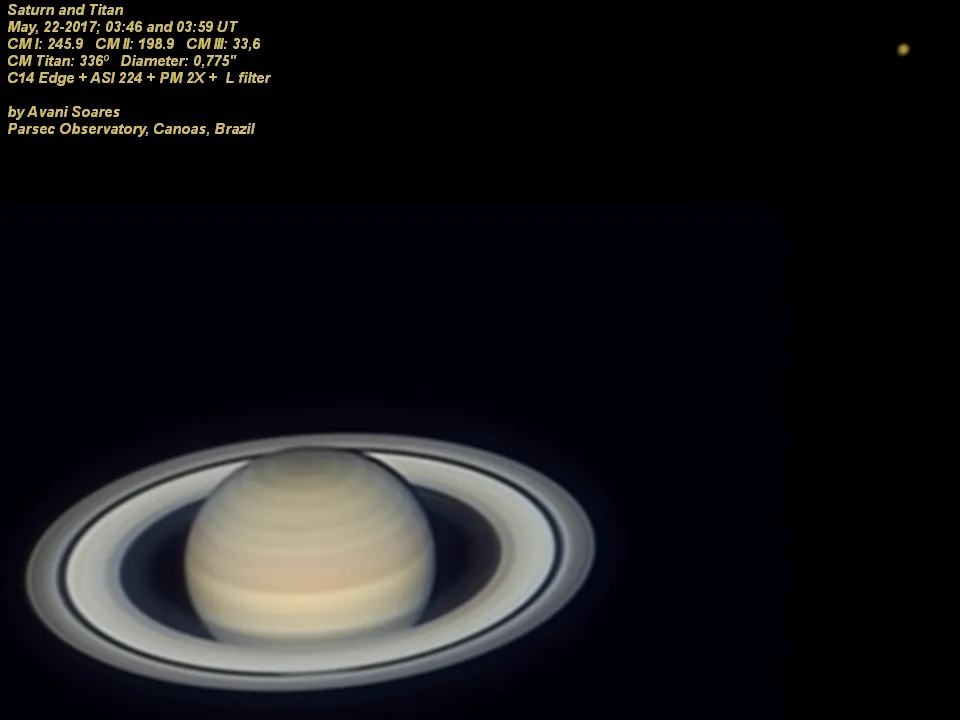

Saturn's moon Titan

Instead of Jupiter's Galilean Moons

Every amateur astronomer remembers their first view of the Galilean moons, Jupiter's four largest satellites, discovered by Galileo in 1610 using his celestial spyglass.

It’s very surprising that Galileo didn’t discover Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, too.

After all, it is clearly visible in binoculars and small telescopes.

But even today, in this age of computerised Go-To telescopes, a surprising number of people have never seen Titan.

If you’re one of them, this is the time to change that.

Discovered by Christiaan Huygens in 1655, Titan is the second-largest moon in the Solar System, with a diameter of 5,150km – bigger than the planet Mercury.

You can see Titan for yourself by finding Saturn, if the planet is favourably placed.

You’ll need an astronomy smartphone app or program to identify which one of the many ‘stars’ around the planet is actually Titan though.

At magnitude +9.0 it will be fainter than many background stars.

Having identified it, keep an eye on it over several nights to see how it moves slowly around the planet.

Almach, Gamma Andromedae

Instead of Albireo, Beta Cygni

Double star observers are a special, select breed.

While other amateur astronomers swoon and drool over the glowing gas and dust clouds of nebulae, the star-frothed arms of spiral galaxies or the rings, cloud bands or dusty surfaces of planets, double star aficionados delight in seeing pairs of stars with sequin-like contrasting colours.

The most famous double star is probably gold and blue Albireo, in Cygnus, but close to the galaxy M31 is another double star that you really should get to know.

Almach, in Andromeda, looks like a single yellow-white star to the naked eye, but look at it through binoculars and you’ll see it has a fainter, more sublime blue-hued companion close to it.

Located 355 lightyears away from Earth, Almach is high in the sky and waiting for you as darkness falls on autumn nights, so don’t just hopscotch past it as you head to the Andromeda Galaxy!

A comet

Instead of The Moon

For some astronomers, the Moon is an unwelcome visitor to the sky, a big, blindingly-bright ball that drowns out all the 'good stuff' and always returns at the wrong time, such as during a meteor shower’s peak or when a comet is at its closest to Earth.

For others, it’s a fascinating world-next-door, with craters, mountains and canyons.

Whichever camp you’re in, for a change why not take a look at an asteroid or comet instead?

For up-to-date info, read our guide to comets and asteroids in the sky tonight.

Star cluster M35

Instead of the Pleiades

Everyone loves the Pleiades – it’s the first star cluster many people find in the sky, because it’s so big and bright and obvious to the naked eye.

Also known as the Seven Sisters because its seven brightest stars can be seen without any optical aids, through binoculars or a telescope this spill of gemstone stars never disappoints.

But there are other clusters around it that deserve your precious eyepiece time too.

Nearby M35, in Gemini, is smaller and fainter than the Pleiades, but beautiful in its own right, even though it's perhaps one of the more obscure of the lesser known astronomy targets on our list.

Visible to the naked eye as a small, out-of-the-corner-of-your-eye smudge close to the feet of Gemini, this fifth-magnitude cluster is more easily seen in binoculars and is resolved as a misty speckle in telescopes.

Around 24 lightyears in diameter, the cluster contains at least 120 stars – perhaps as many as 500 – and lies 2,800 lightyears from Earth.

The Crab Nebula

Instead of: M42, the Orion Nebula

Ask a roomful of astronomers to name their favourite nebula and most will probably say, “The Orion Nebula”.

That's fair enough, as it's a truly spectacular sight in even a small telescope and very easy to find, glowing in the centre of Orion’s Sword.

But nearby lies one of the most important nebulae in the sky.

In 1054, a bright new star appeared in the constellation of Taurus, close to the tip of one of its fearsome horns.

The ‘new star’ was actually a distant sun dying, blown apart in a supernova explosion.

For the following 23 days the supernova shone at magnitude –6.0 and was clearly visible as a spark of light in the daytime sky.

That star has long since faded, but in its place we can see a small misty patch: M1, the Crab Nebula.

This 11-lightyear-wide cloud of gas and dust is completely destroyed by moonlight or light pollution, but under good conditions it can be seen through binoculars and small telescopes.

Large telescopes show its vaguely crab-like shape, which gave it its name.

Star cluster Caroline’s Rose

Instead of the Double Cluster

The Double Cluster is a favourite autumn target for many observers.

Located roughly half-way between the ‘W’ of Cassiopeia and the inverted Y of Perseus, this close pair of open star clusters looks like two piles of tiny diamonds spilled onto black velvet.

But not too far away is a cluster that combines beauty with astronomical history.

Caroline’s Rose is named after its discoverer, Caroline Herschel, sister of Uranus’s discoverer, William Herschel.

Located 7,600 lightyears away, its hundreds of stars span an area of around 60 lightyears.

When viewed through a telescope at high magnification, the cluster’s orange and blue stars, and the dark lanes between them really do resemble a rose with open petals.

Caroline’s Rose is estimated to be 1.6 billion years old; that’s very old for an open cluster, but much younger than any globular cluster.

The Cat’s Eye Nebula

Instead of the Ring Nebula, M57

Planetary nebulae are some of the most subtle and elegant deep-sky objects in the night sky.

The most famous is probably M57, the Ring Nebula, which genuinely looks like a wispy smoke ring through a telescope.

M57 is a summer favourite, but it's still visible in October, over in the west after sunset.

The Cat’s Eye Nebula, NGC 6543 in Draco, is a great alternative if you fancy a change, and is one of the more striking lesser known astronomy targets.

Just over 3,000 lightyears away, and with a magnitude of just over +8.0, the nebula has a roughly lenticular shape in binoculars

When seen through a telescope really does look like a cat’s oval eye, with a bright centre surrounded by a fainter, oval haze.

The nebula has been photographed in great detail by both the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope.

It's a favourite target for amateurs with large telescopes and skies dark enough to use them to their full potential.

M51, the Whirlpool Galaxy

Instead of M31, the Andromeda Galaxy

If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, M31 is the galaxy to gaze at on clear autumn nights.

It’s big (as wide as several full Moons), bright (easily visible to the naked eye) and already high in the sky as darkness falls.

But there are many other galaxies available for your viewing pleasure too, and if you slowly sweep your binoculars around beneath the tip of the tail of the Great Bear, Ursa Major, you’ll see a tiny smudge of pale grey, like an out-of-focus star.

This is M51, aka the Whirlpool Galaxy, a vast spiral of billions of stars more than 28 million lightyears away, roughly equal in size to our own Milky Way.

This month is a fitting time to track down M51; although its beautiful spiral shape wasn’t seen until 1845, when Lord Rosse turned the famous Leviathan telescope on it.

2023 was the 250th anniversary of the galaxy’s discovery, by Charles Messier on 13 October 1773.

Small telescopes show M51 as a small oval-shaped blur, while a large telescope and high magnification will reveal its beautiful spiral shape.

What are your favourite lesser-known astronomy and astrophotography targets? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com

This article originally appeared in the October 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.