When I was getting into astronomy it was always said that, as summer arrives, the lighter nights make observing sessions rather pointless.

What I eventually learnt is that while chasing the dimmest faint fuzzies at the eyepiece might be out of the question in June, the warm evenings can still be a time when treasured celestial memories are made.

There’s certainly no reason to leave the telescope or binoculars gathering dust during summer.

There are some fine star clusters, noctilucent clouds, planetary alignments and more to be seen.

Here we'll show you that summer stargazing and observing can be wonderful, and we've picked out a selection of celestial phenomena for satisfying observing and imaging challenges.

And while our list is tailored slightly more to the interests of an intermediate-level astronomer with photographic kit to hand, there are some great beginner targets scattered among them.

For weekly observing advice and lunar phases delivered straight to your email inbox, sign up to receive the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter.

Beehive Cluster

In June, look out for a beautiful spring target that’s sinking into the west now. Very early in the month you’ll find the beautiful Beehive Cluster, M44, dropping low on the west-northwest horizon as midnight approaches.

It’s the perfect observing target for 10x50 binoculars, or similar, which will show the numerous glittering stars of the open star cluster scattered around a patch of sky that’s roughly a degree across.

On 4 June 2022, the crescent Moon lies about 6.5° from the Beehive Cluster.

With earthshine – when light scattered off Earth lights up the Moon’s night side – showing up at this lunar phase, the arrangement could make for some striking nightscape-style astrophotography compositions.

Once you've found the Beehive Cluster, you could have a go at sketching it. Find out how in our guide to sketching a deep-sky object.

Coma Star Cluster

The Coma Star Cluster is in the L-shaped constellation of Coma Berenices (Berenice’s Hair) and lies about halfway between Denebola (Beta (β) Leonis) and Cor Caroli (Alpha (α) Canum Venaticorum).

The cluster can be tricky to see from locations marred by light pollution, but it can be viewed with the naked-eye from a dark suburban spot.

It looks superb in a pair of 10x50 binoculars and is dominated by 4th-, 5th- and 6th-magnitude stars.

The best time to view the cluster will be in the days leading up to 5 June 2022, after which time the Moon will interfere. Find it about 30–35° above due west around 01:30 BST (00:30 UT).

Discover more targets like this with our pick of the best star clusters to see with the naked eye.

Messier 53

We don’t have to go far to find the next target. M53 a telescopic object suited to a larger scope of 8-inches (200mm) or more: globular cluster M53.

It also sits in Coma Berenices, about 14° away from the Coma Star Cluster.

If you intend to star hop to M53, first identify the extended ‘L’ shape of Coma Berenices.

Then direct your finderscope towards the 4th-magnitude star Alpha (α) Comae Berenices at the other end of the ‘L’ from the Coma Star Cluster.

From here head northeast by about a degree and M53 should fit nicely in the field of view of an eyepiece giving around 70x to 80x magnification.

Constellation Scorpius

If you’re observing or imaging from a location with a clear southern horizon, look towards the constellation of Scorpius, the Scorpion.

This region of the sky is often hidden by the skylines of towns and cities, so it’s a good one to look out for if you’re heading away from home.

From the UK, the constellation will be spanning the meridian around midnight in late June.

Its low altitude makes it suitable for wide-field nightscapes over distant horizons, with the bright stars comprising the pincers and head of the Scorpion balanced against rich Milky Way star fields nearby.

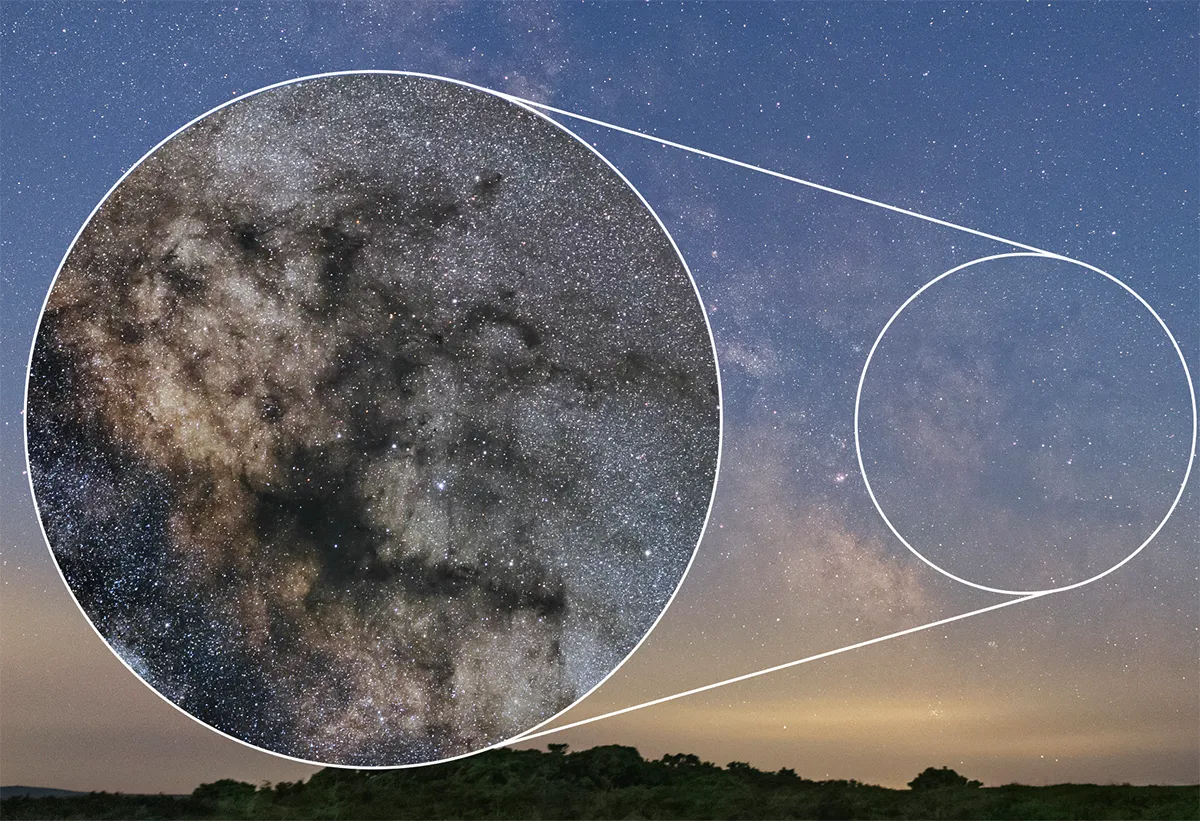

Prancing Horse Nebula

Move (very slightly) to the east from Scorpius and you can turn your attention towards the bright star fields of the Milky Way that lie next door in Ophiuchus, the Serpent-Bearer.

This region is close to the core of the Milky Way and the dense swathes of stars here are crossed by numerous dark nebulae, interstellar clouds of gas and dust within the Galaxy.

One, the so-called Prancing Horse Nebula, is an especially striking astrophotography target, suited to both nightscape and deep wide-field imaging.

In June, with little real darkness around, you might like to try the former.

The nebula is easy to find as it’s mostly contained within a triangle made by the very bright stars Antares (Alpha (α) Scorpii), Lambda (λ) Sagittarii and Eta (η) Ophiuchi.

Noctilucent clouds

As early June comes around we should start seeing noctilucent clouds (NLCs).

These clouds of ice crystals in the mesosphere make wonderful targets for observing and imaging.

Indeed, their always-different, always-changing shapes – as viewed against vibrant twilight skies – are particularly suited to time-lapse astrophotography.

In the evening, look for them low on the northern horizon about an hour after the Sun has set.

You’re looking for thin wisps and tendrils of whitish-blue light, sometimes in snaking river-like forms, other times with wave patterns embedded in bright curtains of light.

Binoculars are an effective way to visually monitor the motions within a display over the course of a minute or so.

Scutum star cloud

Look due south around 02:00 BST (01:00 UT) in June and, at least from the southern parts of the UK, you’ll be able to see the Milky Way rising from the horizon.

Low down in the Milky Way sit the bright stars that make up the Teapot asterism in Sagittarius, the Archer, and above them lies the less prominent constellation of Scutum, the Shield – its most striking feature being the famous star ‘cloud’ that dominates its northern half.

The 'cloud' is really a bright patch of Milky Way star fields that stands out from the band of the Galaxy surrounding it.

It’s visible from dark suburban locations if the sky transparency is good, and it makes a wonderful sight in binoculars if you’re far enough away from light pollution.

Cat's Eye Nebula

What’s the simplest astrophotography setup that you can image a planetary nebula with?

How about a DSLR camera and a medium focal-length lens on a static tripod?If that sounds intriguing, here’s an imaging challenge to try.

The Cat’s Eye Nebula is a planetary nebula around 3,000 lightyears away towards the constellation of Draco, the Dragon.

It’s just about bright enough that, if you have reasonably dark skies, you can pick up signs of it with the kit described above.

To be in with the best chance of detecting the nebula, try a star trail-style shot, in which you take multiple long-ish exposures – 30-seconds at least – and then stack them together with your preferred star trail-creation software.

What you’ll find is that the Cat’s Eye Nebula stands out conspicuously from the stars as a greenish-blue arc.

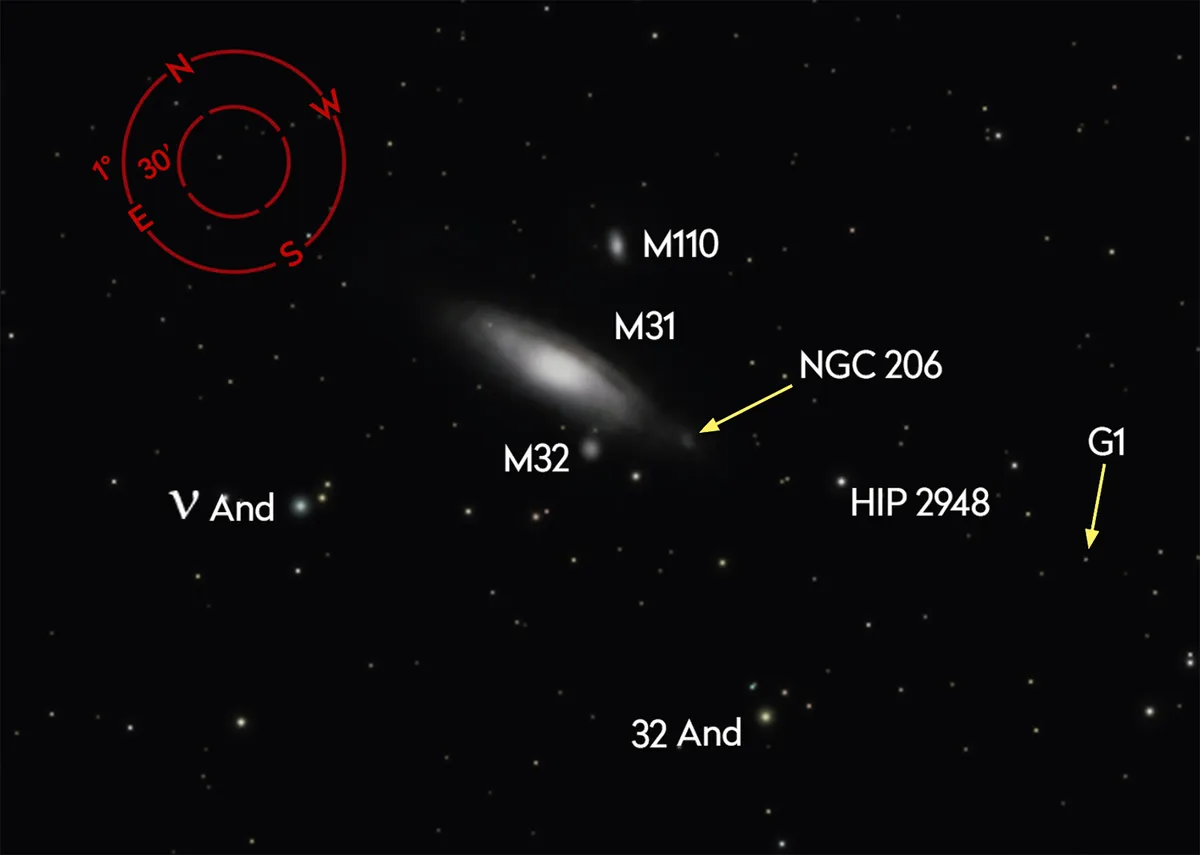

Andromeda's satellite galaxies

Many of us have marvelled at the Andromeda Galaxy, but have you ever looked for its two most prominent satellite galaxies?

M32 and M110 appear close to the centre of Andromeda and are good targets for a medium- or large-aperture telescope.

You’ll find the Andromeda Galaxy sitting about 30° above the northeast horizon around 01:30 BST (00:30 UT) towards the end of June.

A nice way to view M32 and M110 is to select an eyepiece that produces a field of view about 2° across, as this allows both targets to be seen at the same time, with Andromeda’s disc cutting in between.

Cloud trails around the Moon

The chances are that at some point in June or July, clouds will interfere with our observing sessions, but that shouldn’t stop us from trying out some astrophotography.

One way I like to use passing clouds is in long-ish exposure nightscapes of the Moon.

You can use an exposure of several seconds to allow the clouds to trail as they drift by the lunar disc.

The challenge is to find an exposure and ISO setting (and the right gap in the clouds) that gives you detail on the Moon but also in the textures of the clouds.

This requires some trial and error asyou try to balance the exposure and the amount of blurring, which will depend on the exposure length and how fast the clouds are moving.

For more advice, read our guides on how to observe the Moon and how to photograph the Moon.

This guide originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.