December’s cold and frosty nights mark the arrival of the year’s richest meteor showers the Geminid meteor shower.

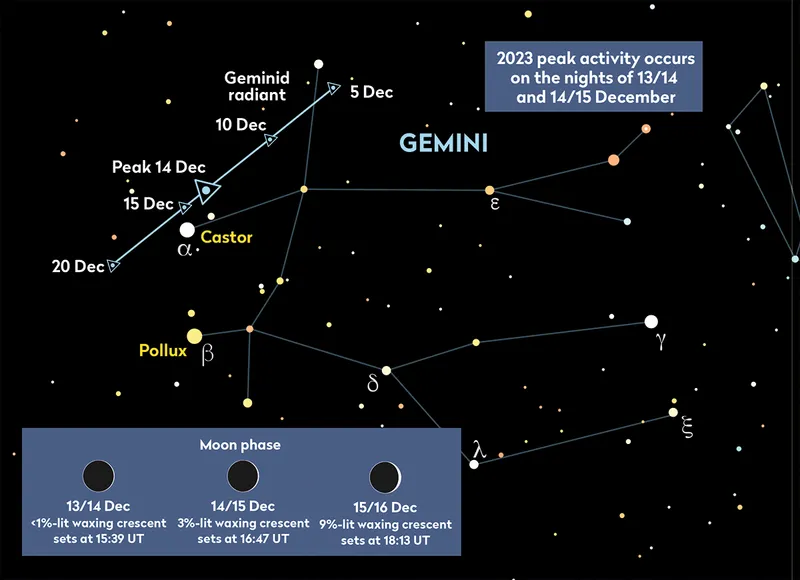

The shower runs from 8-17 December with peak activity occurring 13 - 15 December.

In 2023, the Moon will be out of the way during peak activity, making this year a good opportunity to get out and observe the Geminids.

But what about making useful scientific observations of the Geminid meteor shower? Perhaps while observing this year's shower you could conduct a little citizen science.

Here we'll look at why observations are useful to astronomers and researchers and how best to scientifically record the Geminids.

Tools and materials

- The British Astronomical Association (BAA) meteor section report form (download here)

- A clipboard

- A red light torch

- A star atlas to identify the faintest star you can see

- Warm clothing! The Geminids are in December and so it will be cold

- A deckchair or sunlounger so you can comfortably sit back and look up at the sky

- An accurate clock to record the times of observations

- Food and a hot drink that will keep you going in the cold early hours

What is the Geminid meteor shower?

All meteor showers are produced by either a comet or an asteroid that we call the parental body.

The Geminids are caused by 3200 Phaethon, an Apollo-type asteroid that orbits the Sun every 1.4 years.

3200 Phaethon has a rather eccentric orbit.

The furthest it gets from the Sun is a distance of 2.4 AU (aphelion) but its closest distance (perihelion) is just 0.1 AU: closer to the Sun than the planet Mercury.

3200 Phaethon has the distinction of being the only asteroid in the Solar System to get this close to the Sun!

While it’s in the inner Solar System, heat from the Sun causes particles to escape from the surface of Phaethon and fly away into space.

Eventually, these particles collide with Earth; they burn up as they hit the atmosphere, causing a glowing trail, or what we call a meteor or ‘shooting star’.

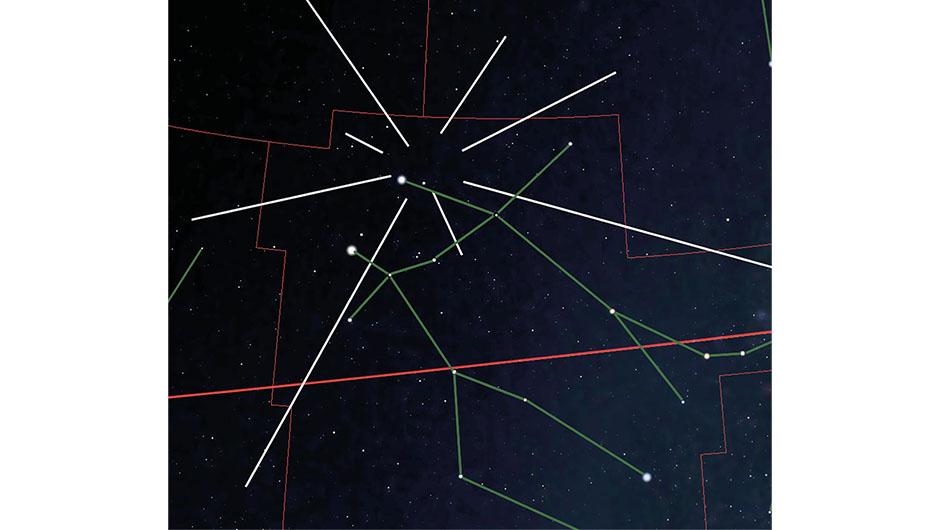

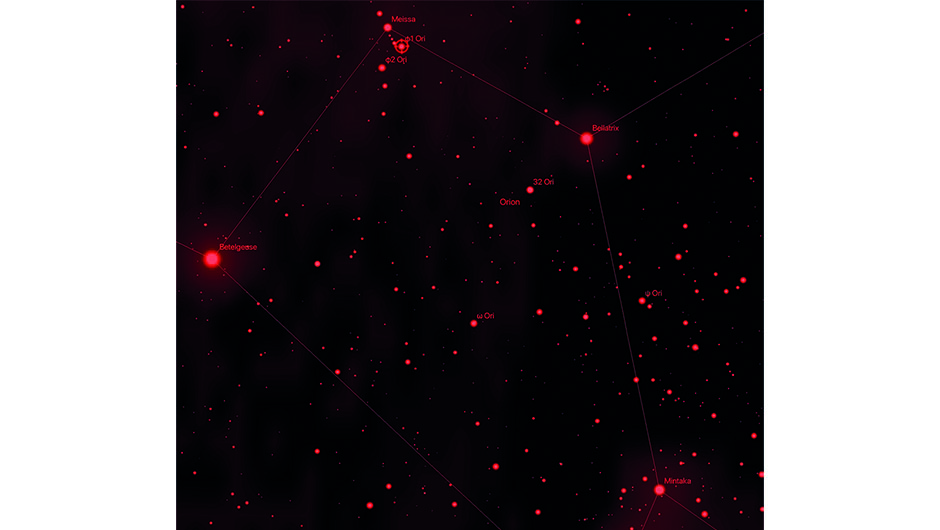

Since Earth is colliding with a cloud of particles, the meteors appear to us to come from one direction in the sky.

This is called the 'radiant' and the location of the radiant gives the name of the shower.

The radiant for meteors in the constellation of Gemini gives the shower its name: the Geminids.

You'll find the radiant for the Geminids near the twin stars Castor and Pollux.

Observing meteor showers for science

Meteor showers are a good opportunity for astronomers to study their parental bodies, so amateur observations are welcomed by organisations like the British Astronomical Association (BAA).

If, for example, analysis of the observations reveals that the radiant has shifted, this could indicate orbital changes.

We can also infer how active the parental object has been during its passage into the inner Solar System.

How to observe

Useful observations of meteors require an organised meteor watch.

You can look for meteors on your own, but it's common to observe in groups, one member acting as a recorder and filling in the form as observers call out their sightings.

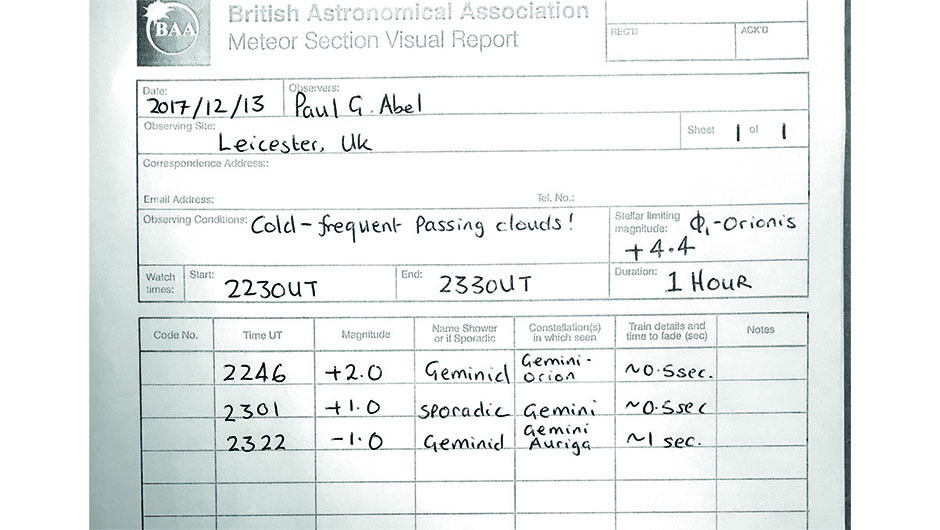

The report form at the link in 'tools and materials' above is available electronically, so you can print it out and use it during your session.

Although the Geminids have a Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) of over 100 meteors an hour, this number can be misleading since it assumes optimum viewing conditions.

I.e. a radiant that’s high in the sky and no light pollution or clouds. In reality you won’t see as many as this.

Geminids tend to be swift and usually white in colour – the streak they leave behind is called a meteor train and it may persist for a few seconds.

You’ll need to record the names of all observers, your location and contact details along with the start and end times (in UT) of your session.

You also need to make a note of the stellar limiting magnitude of your site by locating and identifying the faintest star you can see with the naked eye.

As the watch gets underway, you’ll need to record the times the meteors were observed along with their estimated magnitude.

Remember, not all of the meteors observed will be Geminids!

A true Geminid will have either a short train close to the radiant or a longer one further away; it must also be moving away from the radiant.

If your meteor is not obeying these rules it is what’s known as a ‘sporadic’ and not part of the shower – you should still record it but label it ‘sporadic’.

You also need to include any constellations that the meteor passes and how long it takes to fade.

Once indoors, you should type your observations into the report form and save it on your computer so that you have a good permanent record.

And don’t let the data you’ve collected sit around.

Send your observations to the Meteor Section of the BAA – the scientists there will make good use of the data!