Rupes Altai is an escarpment on the Moon, which basically means it's a slope that has formed due to faulting or erosion.

In fact, Rupes Altai is the most prominent lunar escarpment visible from Earth.

Two surface regions divided by an escarpment will have different heights relative to one another.

This feature has undergone several changes in name. Originally known as the Altai Mountains, it was formally renamed to the Altai Scarp back in 1961, being latinised to Rupes Altai three years after that.

Key facts

- Type: Escarpment

- Size: 480km

- Longitude/latitude: 23.7° E, 24.3° S

- Age: Around 3.9 billion years

- Best time to see: Five days after new Moon (13–15 May) or four days after full Moon (26–28 May)

- Minimum equipment: 10x binoculars

Rupes Altai location

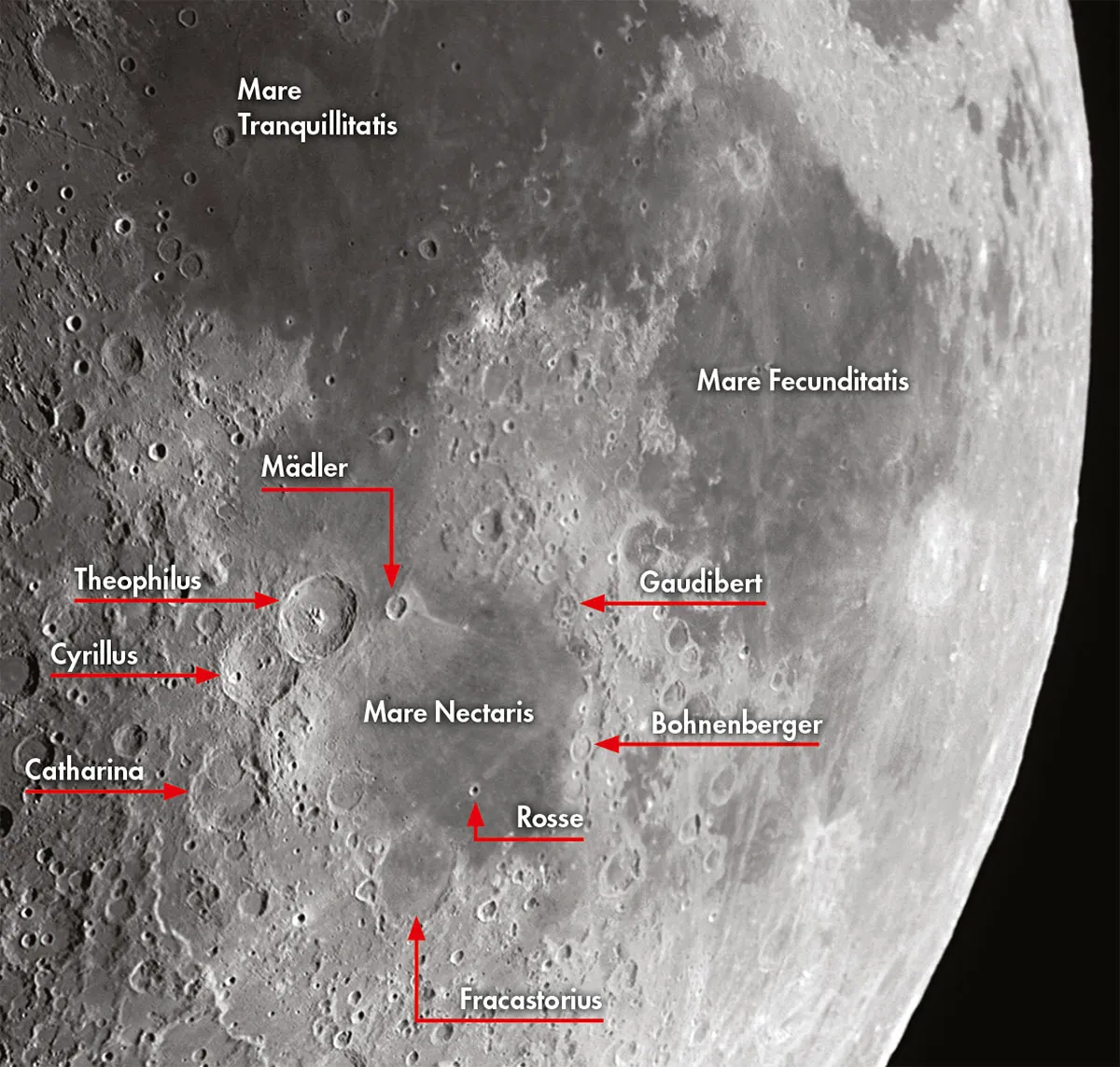

Rupes Altai is associated with Mare Nectaris, as it represents the southwest section of the Nectaris Basin’s rim.

The Nectaris Basin is one of those lunar features that can be difficult to see well, something that may seem surprising considering it’s around 800km in diameter.

The problem is that the rest of the rim other than Rupes Altai is heavily eroded.

Catch the region when the terminator is just to the east of Mare Nectaris and the full extent of the Nectaris Basin is a little easier to imagine.

Observing Rupes Altai

Rupes Altai itself is a magnificent structure best appreciated, as is often the case, when the lunar terminator is nearby.

The best shadows are cast by the escarpment when light is coming from the west – in other words, when the lunar night is approaching during the waning gibbous phase.

At times when the light comes from the east during the waxing crescent phase, Rupes Altai tends to look like a bright squiggle as its slopes catch the Sun’s light face-on.

The escarpment slope has a considerable length, stretching northwest from 88km crater Piccolomini before heading north, running slightly west of 101km Catharina.

Piccolomini sits in the path of the escarpment, a younger crater estimated to be 3.2–3.8 billion years of age that has stamped itself onto the southern extremity of Rupes Altai, bringing the escarpment’s path to a distinct and abrupt end.

The northern extremity is less well defined and peters out as it heads past Catharina.

Under oblique lighting, some of the features here appear to give the escarpment an extended lease of life.

But while the northern part of Rupes Altai would naturally seem to continue north past 98km Cyrillus and 101km Theophilus, where it actually ends isn’t completely clear.

This part of the Moon’s surface is heavily cratered. The mid-section is flanked by two particularly complex, messy regions.

To the southwest is 45km Pons, overlaid by myriad smaller craterlets.

To the northeast is 41km Polybius, which is fairly cleanly presented compared to Pons.

But the region immediately to the west – which includes 28km Polybius C and 22km Polybius F – is rather mixed up. Bringing more order to the north of Pons are 40km Fermat and 17km Fermat A.

One must-see feature that starts at the northern end of Rupes Altai and heads northwest is the magnificent crater chain Catena Abulfeda.

This stretches for at least 230km across the lunar surface and consists of mostly sub-10km craters, the exception being 16km Almanon C.

Have you observed or photographed Rupes Altai? Get in touch by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com