Winter is a great time to observe constellations in the night sky. The nights are dark and long, making star patterns easy to spot.

The changing of the seasons brings a change in the constellations, slowly nudged from east to west as we continue our journey around the Sun.

There are some, known as circumpolar constellations, that are visible all year long.

If you’re a complete beginner to constellations, you may be wondering what they are. Quite simply they are grouped patterns of stars in our night sky.

For thousands of years our ancestors looked to the sky, observed and named them after animals, objects and mythological characters.

You will need a bit of imagination as you try to identify each one as the constellation often looks nothing like its name!

How many constellations are there?

In 1930, the International Astronomical Union formally recognised 88 constellations that can be identified on the celestial sphere: an imaginary globe that surrounds Earth.

Each constellation can be found using celestial coordinates: right ascension, and declination. These are similar to latitude and longitude, but don’t worry, you can easily find the constellations just by recognising the pattern.

Some constellations are visible all year round and never sink below the horizon so you can see them whenever there is a clear sky.

These are called circumpolar as they are close to the celestial poles, the imaginary point in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres where the line of Earth’s axis extends out into space to meet the celestial sphere.

Spotting constellations in winter

Colder, clearer evenings are perfect for enjoying the winter constellations as well as a few deep-sky objects like galaxies, star clusters and nebulae found within them.

You can see these beautiful pin-prick patterns of light, hot fiery stars and clouds of dust and gas with your naked eye, using binoculars or a telescope. Best of all, you don’t need to be in a completely dark-sky area to see them.

This short tour highlights a handful of constellations that, with a clear horizon, are easy to spot after 20:00 UT. Plus, there are a few tips as to what you may find hiding within them.

If your horizon is obstructed by trees or buildings, you may need to wait a little longer until the constellation is higher in the sky. So, wrap up warm, grab this guide and step outside.

You can always use a star chart, astronomy app or free software like Stellarium to help you find each object.

And track down our pick of the best winter stars too, while you're out looking for winter constellations.

And if you're reading this article at a different time of year, read our guides to the best summer constellations and best summer stars.

Orion

If you were to ask any astronomer which winter constellation you should choose to kick off your stargazing journey, the answer will be Orion, the Hunter (see picture, above). Dominant against the darkness and easy to recognise, we can use it to navigate, so we’ll begin here.

Orion can be found rising in the east after sunset and it’s easy to identify from the three stars aligned in an almost straight line.

These three stars – Alnitak (Zeta (ζ) Orionis), Alnilam (Epsilon (ε) Orionis) and Mintaka (Delta (δ) Orionis) – form Orion’s Belt, which is an example of an asterism (a pattern of stars within a constellation).

Orion is a winter favourite because of its two blazing, non-Belt stars – Betelgeuse (Alpha (α) Orionis), a bright orange star 1,000 times bigger than our own Sun, and Rigel (Beta (β) Orionis), a cooler blue supergiant – and its fantastic nebula.

The Orion Nebula, M42, lies in the centre of Orion’s Sword, a shorter line of three fainter stars that hangs down from the Belt. The nebula looks like the middle ‘star’ of the Sword to the naked eye, but a bit fuzzier than the stars above and below it.

Composed of dust and gas and located 1,344 lightyears away, it is a famous nebula for naked-eye observing and perfect for beginners. A pair of 10x50 binoculars will enhance this diffuse cloud of dust and gas, while a small scope will bring out its darker and lighter patches.

If astrophotography is your thing, read our guide on how to photograph the Orion Nebula.

Gemini

The constellation of Gemini, the Twins, borders Orion on the Hunter’s upper left shoulder. Gemini’s two prominent stars, Castor (Alpha (α) Geminorum) and Pollux (Beta (β) Geminorum) are easily found: follow an imaginary line from Rigel to Betelgeuse and keep going until you reach two prominent stars positioned one above the other. This method is known as star-hopping.

Castor and Pollux each form one of the heads of the Twins, which at this time of the year look like they are lying down with their feet near Orion’s raised arm.

Taurus

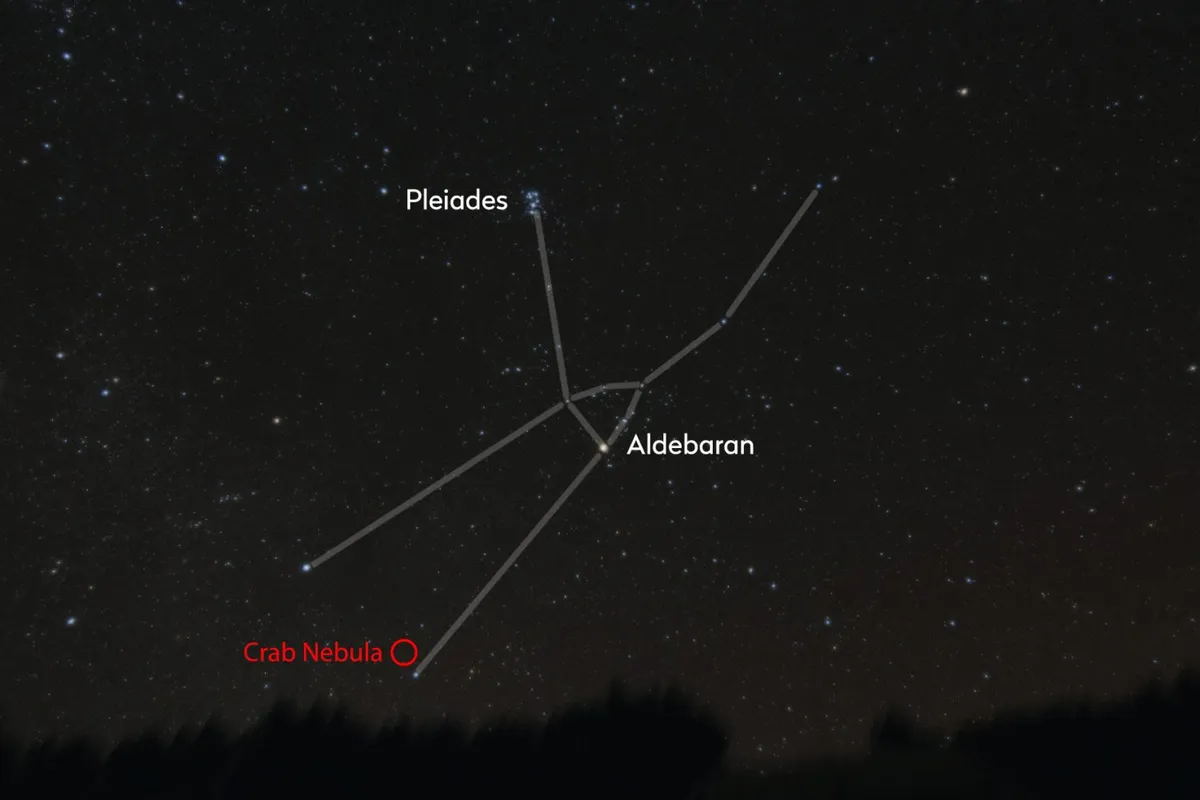

To find the next constellation use Orion’s Belt as a reference point again, and allow your gaze to drift upwards to the right of Orion’s shoulder.

You’ll spot a bright orange star called Aldebaran (Alpha (α) Tauri), the brightest star in the constellation of Taurus, The Bull. Also known as the ‘Eye of Taurus’, this red giant is much cooler than our Sun.

Taurus hosts two fantastic open star clusters and Aldebaran is positioned within one of them, the Hyades, which appears like a ‘V’ shaped pattern of stars on its side.

Located just above this is another cluster called the Pleiades (see above), also known as the Seven Sisters because of the seven stars you can see with the naked eye. A pair of binoculars will reveal many more of the dimmer stars within each cluster.

Ursa Major

Continuing with the tour, find Gemini again and sweep your eyes to the north.

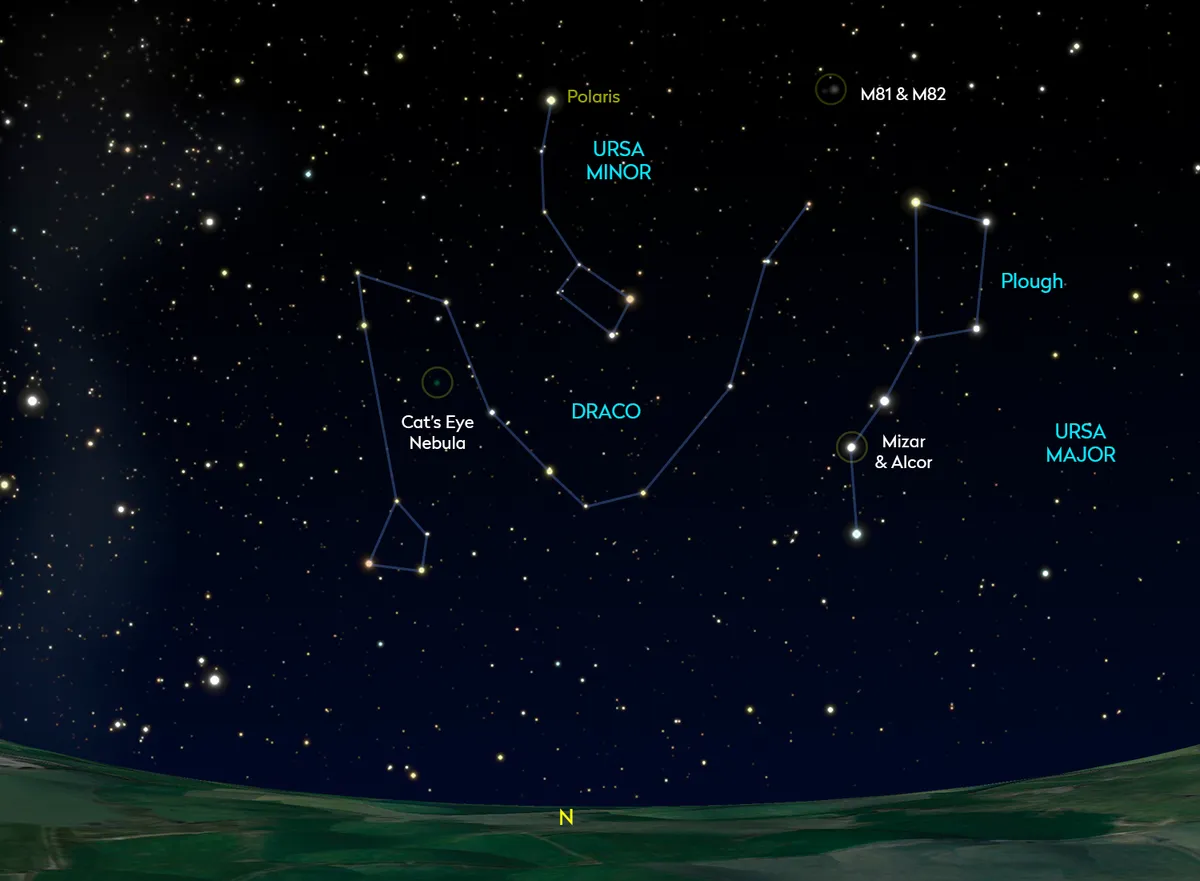

They will settle upon two constellations you may well have spotted before: Ursa Major, the Great Bear and Ursa Minor, the Little Bear, whose tail ends with the North Star, Polaris (Alpha (α) Ursae Minoris).

Draco the Dragon winds its way between Ursa Minor and Ursa Major. Visible all year, these constellations hold some surprising targets.

Ursa Major’s back and tail make up that familiar asterism the Plough. At the bend in the Plough’s handle lie Mizar (Zeta (ζ) Ursae Majoris) and Alcor (80 Ursae Majoris), a double star.

Can you make them both out with your eyes alone? Mizar is brighter, so reach for your binoculars or scope if you struggle to see Alcor.

Draco is a useful pit stop to locate the wonderful Cat’s Eye Nebula, NGC 6543. This is not a naked-eye object, but larger telescopes will show the nebula as a blue-green disc.

Cassiopeia

Keeping your gaze high and looking west from Polaris, navigate to the inverted ‘W’ or ‘M’ shaped pattern of stars; these five prominent stars are an asterism in the constellation of Cassiopeia, the Queen.

Cassiopeia lies in the band of the Milky Way so grab your binoculars and choose one of the ‘W’s five stars to focus on. The area of the sky around each one will open up and appear thick with stars.

Andromeda

The final three constellations to enjoy are Andromeda, the Chained Princess; Perseus, the Greek Hero and Auriga, the Charioteer. Once you have located Andromeda to the west of Cassiopeia, you can hop constellations with ease right back to Orion.

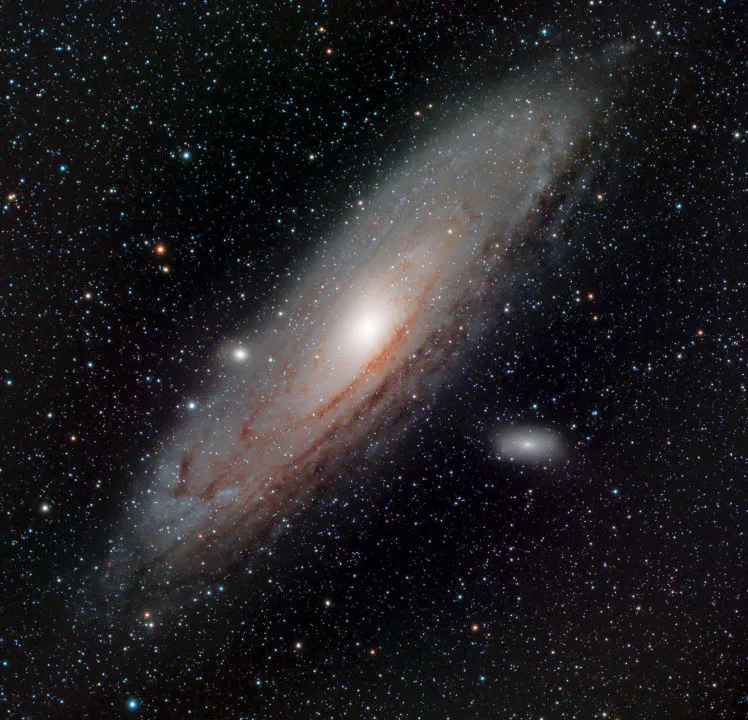

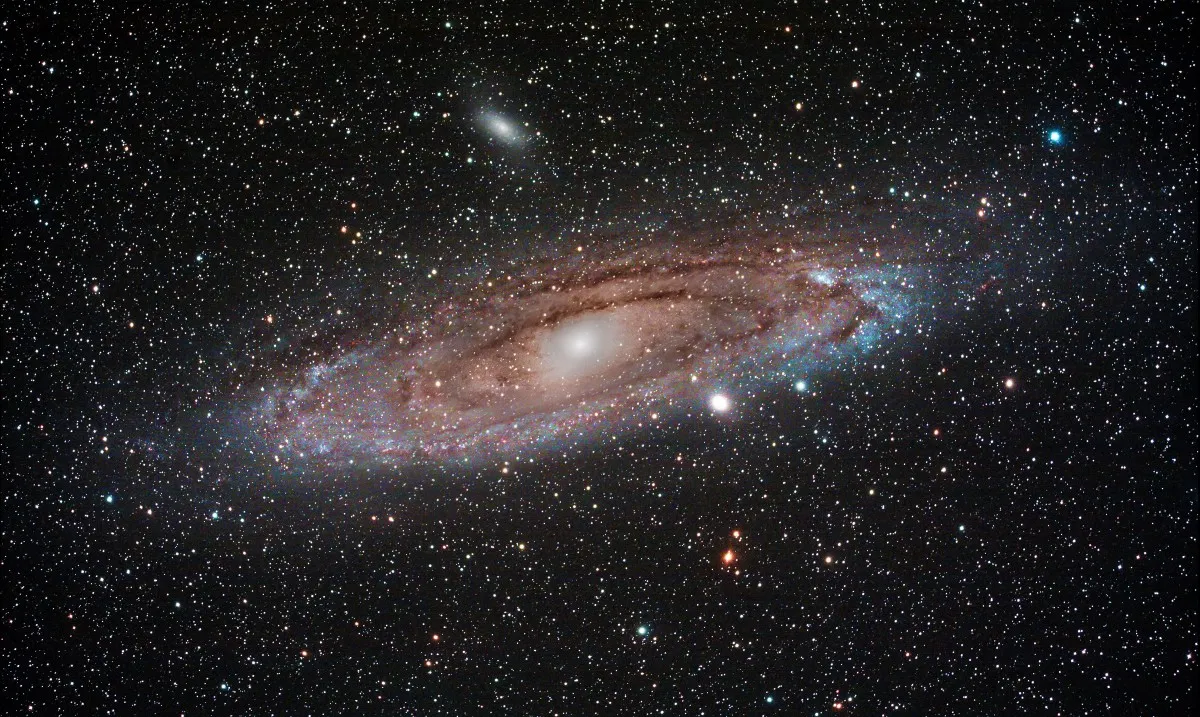

The not-so-hidden gem in Andromeda is the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, 2.5 million lightyears away. With dark-adapted vision, you can see the Andromeda Galaxy your naked eye in darker sky areas.

A telescope will reveal its neighbouring galaxies, M32 and M110. Andromeda’s brightest star, Alpheratz (Alpha (α) Andromedae), also forms part of the constellation of Pegasus, the Horse, which lies to the south of Andromeda.

Perseus

Cast your eyes up from Andromeda to Perseus lying in wait overhead. Locate Algol (Beta (β) Persei), the demon star, the constellation’s brightest member.

The brightness of this eclipsing binary multiple star system can fluctuate over just one evening as two of its members revolve around each other.

Auriga

Finally, look to the lower left of Perseus to find Auriga, the Charioteer, a prominent constellation in the winter sky. Its startlingly bright shimmering star Capella (Alpha (α) Aurigae) is a real showstopper.

Comprising two binary star systems, it is the sixth brightest star in the sky and the third brightest in the Northern Hemisphere.

The winter constellations are revered by astronomers, as they herald a season of long nights observing ahead. You will be astounded at the sights you can see from your own back garden, leaving you keen for spring to stay in the wings a little longer.

10 objects to observe in winter constellations with binoculars or telescope

The Pleiades, M45

Located in Taurus. This open cluster is the jewel in winter’s crown; binoculars will bring many more of its icy blue stars into view.

Orion Nebula, M42

Located in Orion. A winter favourite, even a small pair of 10x50 binoculars will bring out this stellar nursery’s grey-green nebulosity.

Alcor

Located in Ursa Major. Grab your binoculars to see this binary star shining close to its brighter companion, Mizar.

Andromeda Galaxy, M31

Located in Andromeda. You can see the Milky Way’s largest galactic neighbour with the naked eye, but binoculars will bring out its bright core.

The Double Cluster

Located in Perseus Located between Cassiopeia and Perseus, this sparkling Double Cluster will be brought to life through binoculars.

Trapezium Cluster

Located in Orion. Sitting within the heart of the Orion Nebula, the four stars in this open cluster are easily seen with 50x magnification.

Crab Nebula, M1

Located in Taurus. A telescope with 50x magnification will bring this nebula to life as a hazy patch of gas and dust through the eyepiece.

Bode’s Galaxy, M81 and Cigar Galaxy, M82

In Ursa Major. Telescopes with 50x magnification will bring out the spiral structure of Bode’s Galaxy and the Cigar Galaxy’s rod shape.

Pinwheel Galaxy, M101

Located in Triangulum. This face-on spiral galaxy is best seen with averted vision. A scope with 50x magnification is recommended.

M35

Located in Gemini. Viewed through a telescope on frosty nights this open cluster is a glittering treat; a magnification of 25x is recommended.

This article originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.