This is a trip across the night sky, looking at 10 of the best stellar groups visible through binoculars in Autumn.

We’ve chosen several large targets that are arguably better through binoculars than anything else – it would be daft to omit these – as well as targets that help you develop useful observing skills, and a couple that push these skills to their limits.

There are even several circumpolar objects that will be visible in UK skies throughout the year, so you can continue to observe them if you wish.

We recommend 10x50 binoculars for our autumn stargazing list, but all of the objects are visible with a smaller pair.

If you're new to binocular astronomy, read our top tips for binocular astronomy, or seek out your first pair in our guide to the best binoculars for astronomy.

Alpha Persei Moving Cluster

Let's get things going with a circumpolar sight that’s easy to find. The Alpha Persei Moving Cluster extends 4° southeast from Mirphak (Alpha (α) Persei).

When you track it down, you should see stars shining with an intense blue-rich whiteness that indicates that they are young stars. In binoculars, they are said to ‘sparkle like diamonds on black velvet’.

The cluster is said to be ‘moving’ because all the stars have the same proper motion (their apparent movement on the night sky).

The reason we’re starting here though is that they’re a great place to ensure your binoculars are perfectly focused: focus them until you get the maximum number of visible stars.

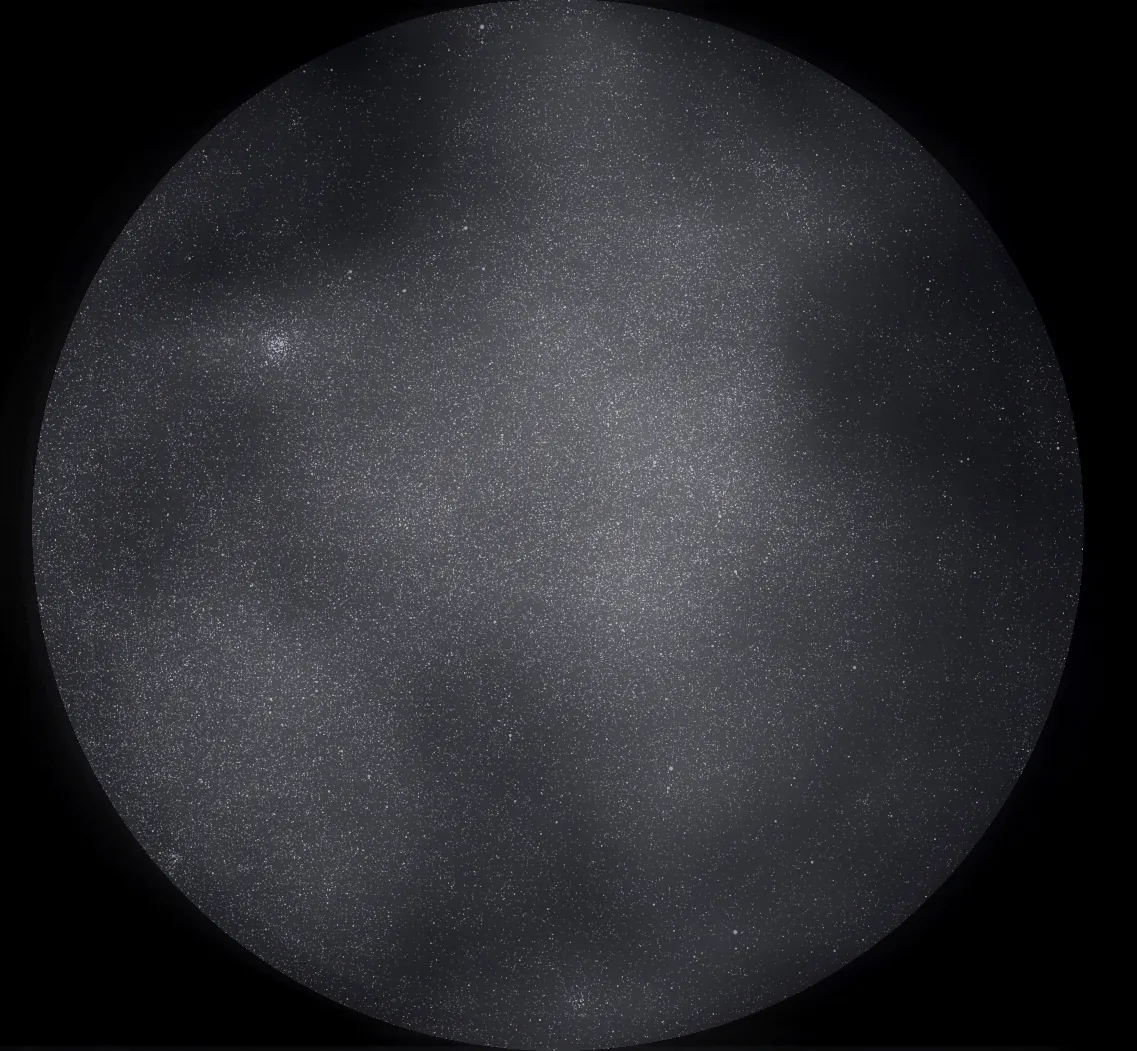

Scutum Star Cloud

With our binoculars in crisp focus, it’s time to take a trip over to southerly skies to look at a duo of sights, starting with the spectacular Scutum Star Cloud.

Located in the southern sky, it’s so easy to find that it has been mistaken for a real cloud on a clear night.

Note how there seem to be ripples of stars; these are formed by indistinct dark nebulae that weave through it.

The richest part is the densest known open cluster, M11, the Wild Duck Cluster. Were it not so rich, it would be very difficult to distinguish from the background star cloud, which itself forms one of the most densely packed regions of the Milky Way.

Poniatowski’s Bull

About 15° northwest of the Scutum Star Cloud we find another ideal object for binoculars. Poniatowski’s Bull has a diameter of about 4° and so fits comfortably in the field of view of 10x50 binoculars.

The brightest stars include 66, 67, 68, 70 and 73 Ophiuchi, which form a V-shape similar to the Hyades cluster in Taurus, hence its common name.

The Coathanger asterism

By now you should be getting your eye in, so we’ll leave the southern skies and travel up to Vulpecula and do our first star-hop. Star-hopping is a way of finding a target by navigating from a bright, easy-to-find object to locate less obvious ones nearby.

Start at Anser (Alpha (α) Vulpeculae) and navigate 5° (about one field of view of 10x50 binoculars) south, where you’ll find The Coathanger asterism – a popular star-party piece, because it looks like an everyday object.

Even 20mm binoculars will reveal the 10 brightest stars that give this asterism its name.

Its formal designation is Collinder 399, but it’s also known as Al-Sufi’s Cluster after the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi who first recorded it back in the 10th century.

Or Brocchi’s Cluster after the astronomer who used it to determine the limiting magnitude of his telescopes.

For our next batch of targets, we’ll need to take a slightly larger trip across the sky, requiring a double star-hop to find our next target.

Imagine a line from Navi (Gamma (γ) Cassiopeiae) through Ruchbah (Delta (δ) Cassiopeiae) and extend it for 7.5° (about one and a half fields of view).

The Muscleman Cluster

Look for a very close pair of small open clusters, the Perseus Double Cluster (you might be able to see them with your naked eye as a single fuzzy blob).

But this isn’t our final destination: from the side nearest Cassiopeia there is a 2° curved chain of stars leading northwards to Stock 2, also known as the Muscleman Cluster.

This gets its name from the stick-man figure made by its brighter stars. He stands with his feet to the east in a bicep-flexing pose, wielding the Double Cluster on a leash (the starry chain that led us here).

The connection between the Muscleman and the Double Cluster is purely illusory: the Double Cluster is nearly seven times as far from Earth as the Muscleman.

Kemble's Kite

Our next asterism is Kemble’s Kite, named for the prolific Canadian binocular observer, Father Lucien Kemble (1922-99), who observed it with 7x35 binoculars.

A line from Segin (Epsilon (ε) Cassiopeiae) through Iota (ι) Cassiopeiae leads to Gamma (γ) Camelopardalis, 8° further northeast.

Approximately 1.5° west of Gamma (γ) Camelopardalis, you’ll find a yellowy-orange star, V805 Cassiopeiae.

V805 is the brightest of a 1.5° long group of 10 stars (mag.+8.0 and +9.0) that form a diamond kite with a tail that flows southwards towards Perseus. This is our target.

Once you have identified it take a look at the star at the kite’s northern tip: it is a double star that is easy to split: both its stars are mag.+8.4, and are 103 arcseconds apart.

Can you detect any difference in the star colours?

Kemble's Cascade

Camelopardalis doesn’t have any stars brighter than mag. +4.0, which makes it rather indistinct in typical UK skies, so for the next target we’ll use the brighter stars of Cassiopeia to star-hop again.

We are trying to locate Kemble’s most famous object: Kemble’s Cascade. This time, we imagine a line from Caph (Beta (β) Cassiopeiae) to Segin and, using outstretched fingers as distance markers, extend it for the same distance into Camelopardalis.

Without shifting your gaze, raise your binoculars to your eyes; if you don’t see the Cascade, you are almost certainly too low, so pan upwards. It is a straight line of 15 mag.+8.0 stars with a brighter mag. +5.0 one in the middle.

It extends 2.5° northwest-southeast and has an open cluster, NGC 1502, near the southeastern end. It’s vertical during September evenings; imagine a ribbon waterfall with the cluster as a splash-pool at the bottom.

Eddie's Coaster

Our next asterism is not immediately apparent in images or on star charts, but it is very obvious in 10x50 or 8x42 binoculars under fairly dark suburban skies.

About 3° north of Gamma (γ) Cassiopeiae there is a double-peaked wave of mag. +7.0 or +8.0 stars, ‘Eddie’s Coaster’, reminiscent of a roller coaster.

Eddie Carpenter is the West Country amateur astronomer who found it and showed it to his friends; cast around the sky when you observe and you too may be the first to find something with which you can delight others.

Now that you’ve got the hang of navigating around the night sky, it’s time to hunt down something a bit more challenging for our final two targets.

Little Queen

First up is the Little Queen, a small replica of the W-shaped asterism of Cassiopeia, hence its name.

First, you must identify Chi (χ) Draconis and, in the same field of view, 1° towards Tyl (Epsilon (ε) Draconis), you will find a little triangle of mag. +7.0 stars.

Either side of the star nearest Tyl, you will see a pair of fainter mag.+8.0 stars that create the ‘W’-shape of which the triangle is part.

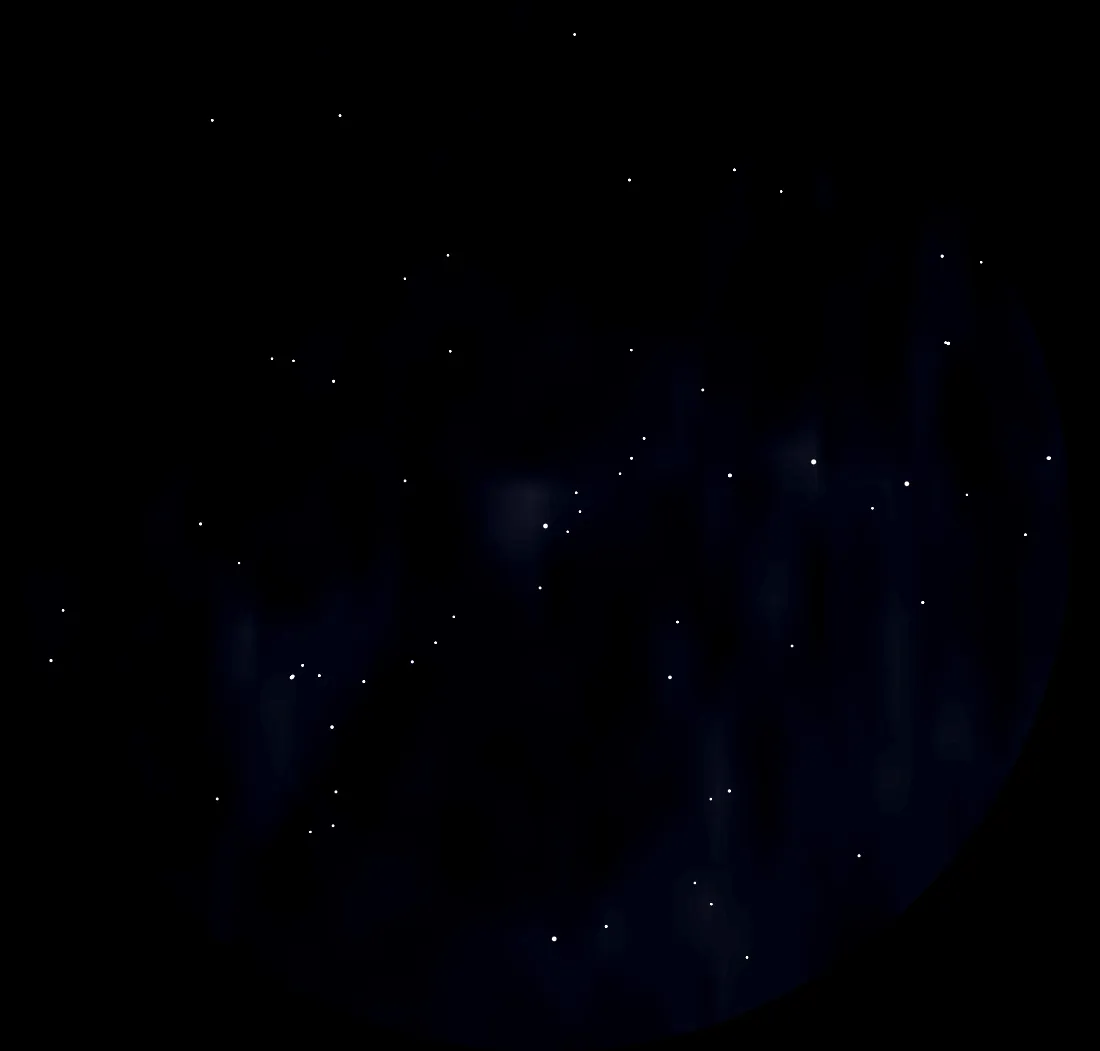

North America Nebula

Finally, we come to the North America Nebula. To give yourself the best chance of detecting it, wait for Deneb (Alpha (α) Cygni) to be high in a very transparent sky. The nebula’s centre is about 3.5° east-southeast of Deneb.

You’re going to need averted vision, so direct your gaze to the edge of the field of view while you concentrate your attention on the centre.

What you are initially trying to detect is the dark nebula that forms the ‘Gulf of Mexico’. Once you can see that darker patch, the brighter part of the North America Nebula becomes more apparent.

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.