For those new to astronomy, staring into the clear night sky and seeing hundreds of points of light can lead to a common conundrum: how will I ever find my way around this bewildering confusion of stars?

One way is to buy a telescope with a Go-To mount, which can take you to any object in its database at the press of a button.

But there is a much simpler alternative, tried and tested over thousands of years, which experienced observers still use to find objects we cannot see with the naked eye.

We call this star hopping.

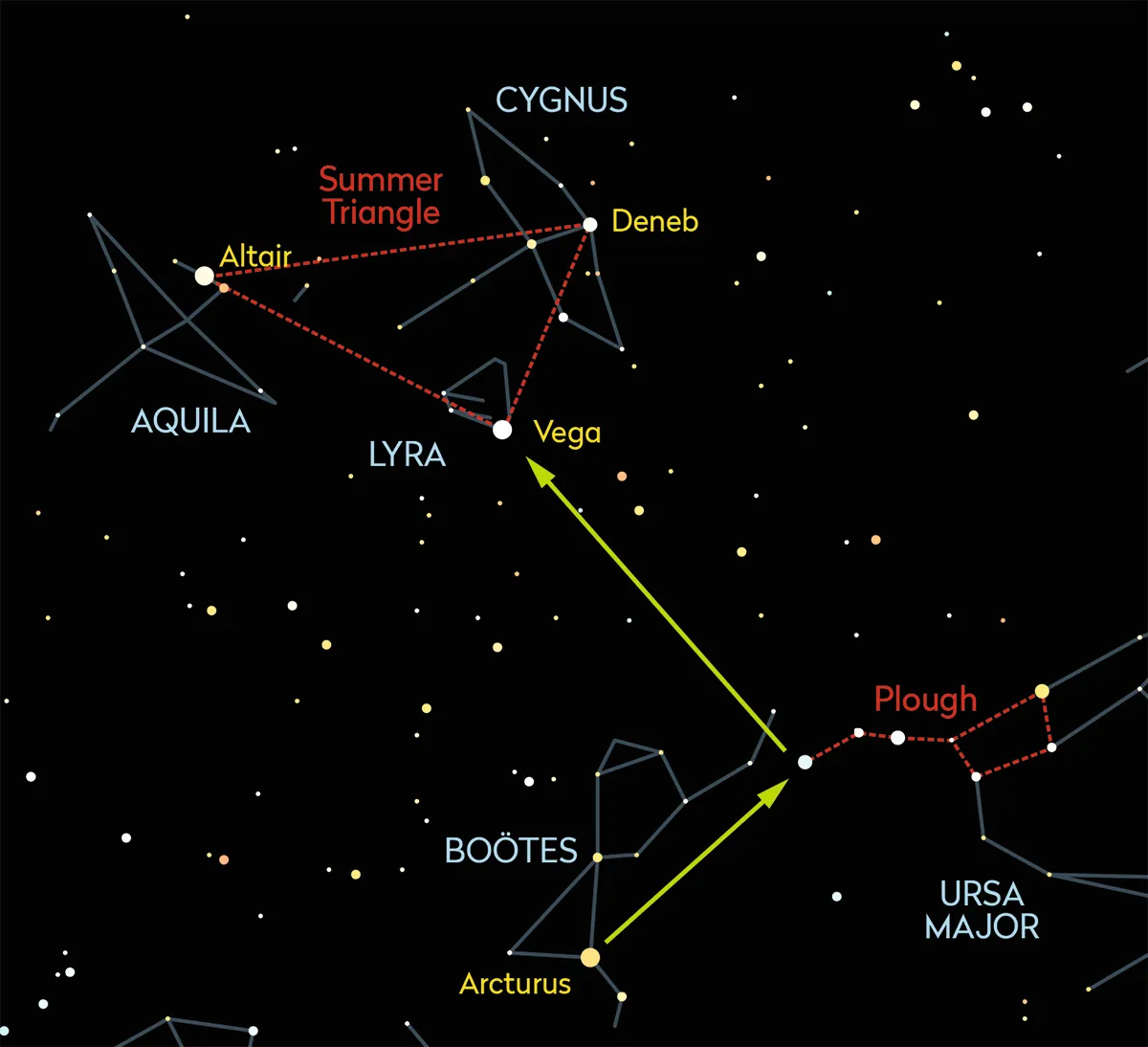

The brighter stars form recognisable patterns – constellations, asterisms, and even simple geometric shapes – and we can use those patterns as ‘jumping off’ points to less obvious and fainter regions or objects of interest.

Some of these shapes may be contained within a single constellation, as is the case with the Plough in Ursa Major and the W of Cassiopeia, but others can stretch across several.

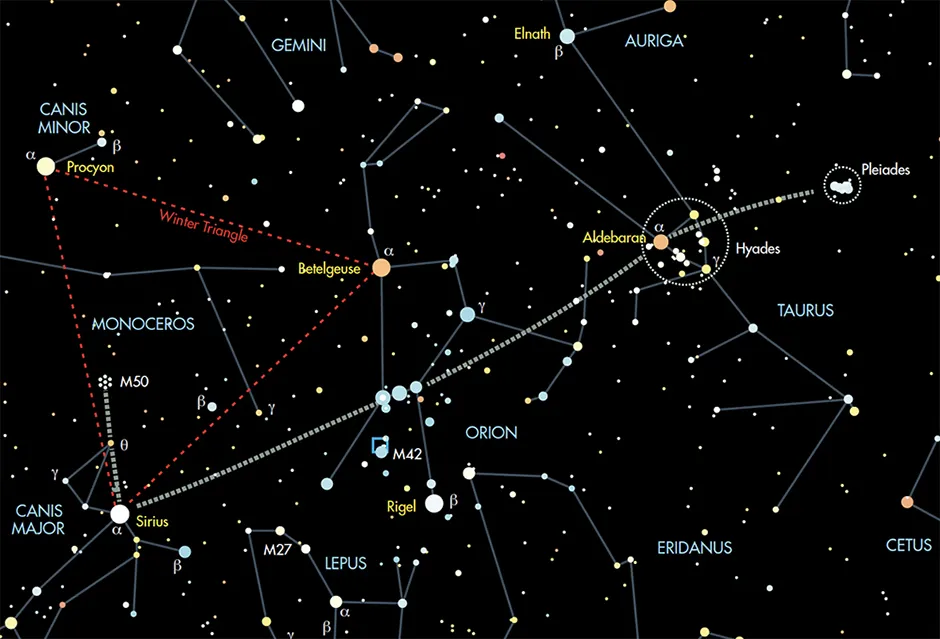

Take the Winter Triangle for instance: its spans Orion, Canis Minor and Canis Major.

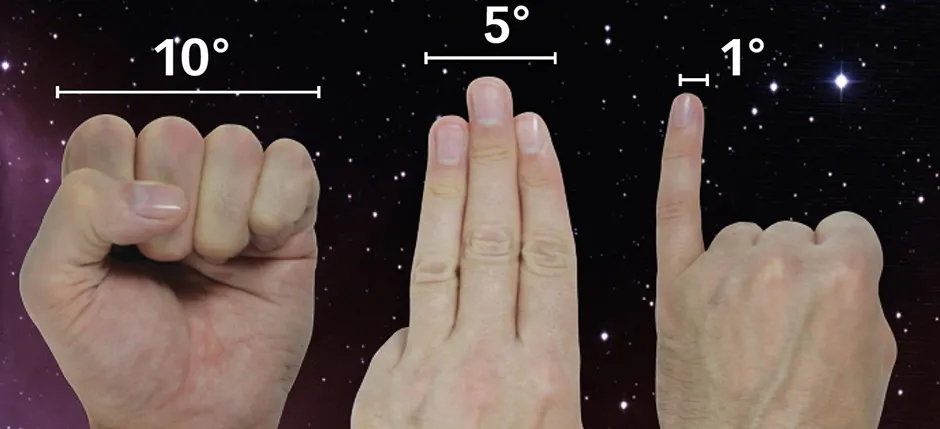

All you need for this remarkably useful technique is a star chart, a red light torch so you can read it outside without compromising your night vision, and some way of measuring the angles between objects.

For this last instrument we're fortunate that nature has already provided us with a rudimentary angle measurer: the hand at the end of your outstretched arm offers an easy approximation of angles ranging from 1° to 25°, as shown in the diagram on the previous page.

An alternative to a star chart is a planisphere, which can show you the sky for any date and time.

If you have a planisphere, set the time on the hour ring to the day on the date ring and it will show you the sky above you.

Search for patterns

One thing you will need to practice is relating the scale of your star chart to the scale of the sky.

Find a constellation or asterism in the sky and then locate the same group on your chart: you will probably be surprised at how much bigger it looks in the sky!

Now look for other prominent groups of stars on your chart and locate them in the sky, trying to keep the relative scales in mind. Reverse and repeat.

Take your time with this: you are building a firm foundation that will serve you well for the rest of your observing career.

The key to star hopping is accurately estimating directions and distances.

For directions, use pairs of bright stars that approximately align to your target object.

If no such stars are available, we may estimate angles from lines of stars.

We can compare the distances we want to the distances between bright stars.

Alternatively, if we know the angular distance from a star, we can use our hands to estimate those distances.

When you transfer these skills to binoculars or telescope finders, make sure you know the angular diameter of the field of view, as you can use this to estimate angular distances.

Start with the star hops suggested here, then devise some of your own.

With a bit of practice, the bewildering confusion will become a familiar playground for you to navigate with confidence.

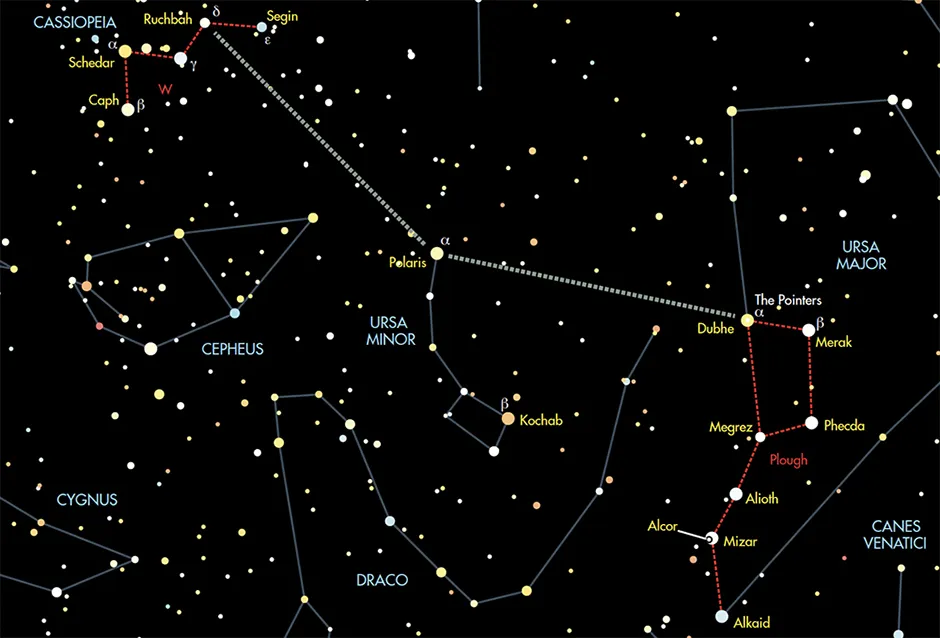

How to find the pole star

The ability to locate the north celestial pole is fundamental to astronomy.

If you can see the Plough asterism in Ursa Major, just use the 'Pointers' Merak and Dubhe (Beta (β) and Alpha (α) Ursae Majoris).

These lead directly to the pole star, Polaris (Alpha (α) Ursae Minoris), which is slightly more than a hand span from Dubhe.

If the Plough is obscured, use the wider ‘V’ of Cassiopeia’s W and divide the V angle into thirds.

Take a line through the third of the angle nearest Segin (Epsilon (ε) Cassiopeiae) and extend it by one hand span.

Learning your way around the sky

Extend a line through Orion’s Belt northwest for 22°, where you will find a bright orange star, Aldebaran (Alpha (α) Tauri), at one tip of a V of stars.

This is the Hyades open cluster. Now extend it 14° farther on and you will find the Pleiades open cluster, commonly called the Seven Sisters.

Return to Orion’s Belt and look about 20° southeast to the bright star Sirius (Alpha (α) Canis Majoris) which, with Betelgeuse (Alpha (α) Orionis), is part of the Winter Triangle asterism.

Imagine that Sirius and Betelgeuse are the base of an equilateral triangle. At the other apex is the third star, Procyon (Alpha (α) Canis Minoris).

We’ll finish with a binocular star hop.

Start at Sirius and look 5° towards Procyon, where you will find the star Theta (θ) Canis Majoris.

Nearly the same distance further on lies M50, an open cluster that will appear as a fuzzy patch in your binoculars.