Have you ever wondered how to find planets in the sky? How do you tell the difference between a star and a planet in the night sky?

If you’ve just started stargazing, it may seem hard to find and identify the Solar System’s planets using your naked eye, without a planetarium to lend a hand, amidst all the stars you can see.

This is a useful skill to have, though, as it’s not as difficult to master as it might seem, and it is even possible to see the planets without a telescope.

But at the risk of pointing out something obvious, there aren’t any labels on the sky.

In this guide we'll reveal top tips on how to find planets in the sky.

For extra help on how to find planets in the sky, read our yearly guide on visible planets, month-by-month.

And if you're really struggling, read our guide to the best smartphone astronomy apps.

How to find planets? Locate the ecliptic

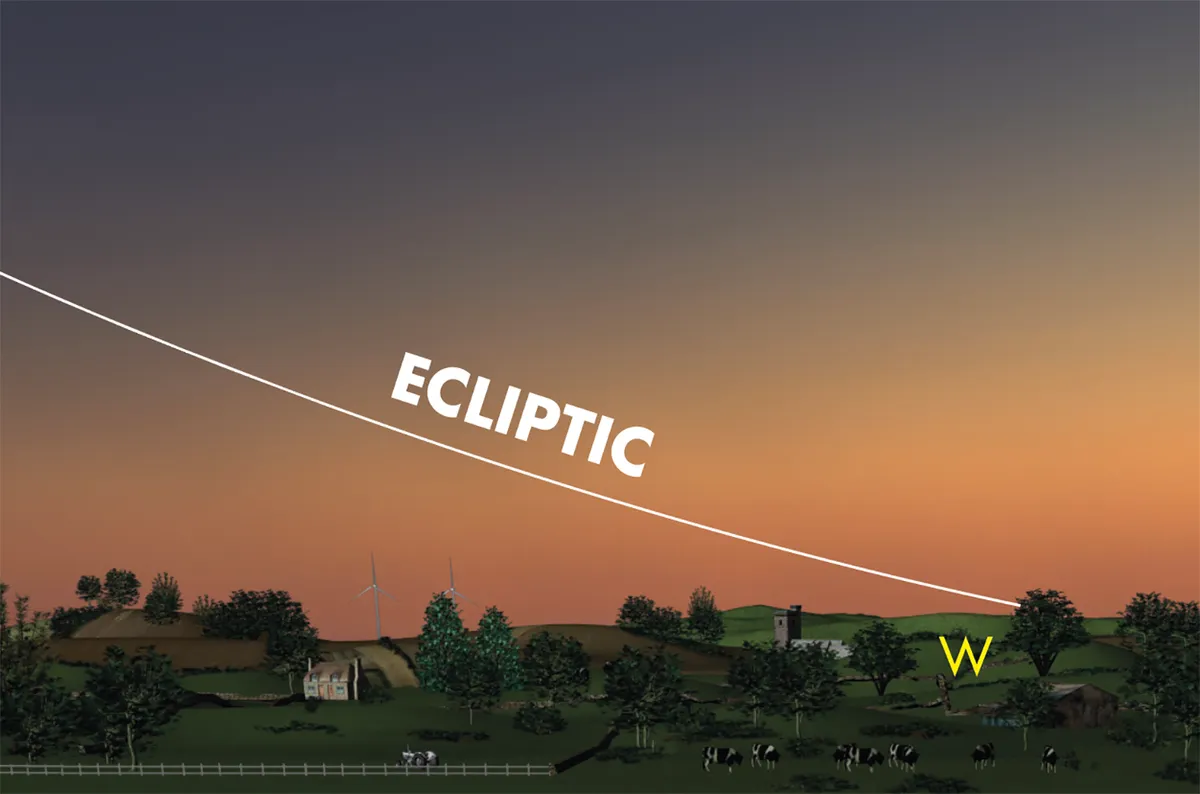

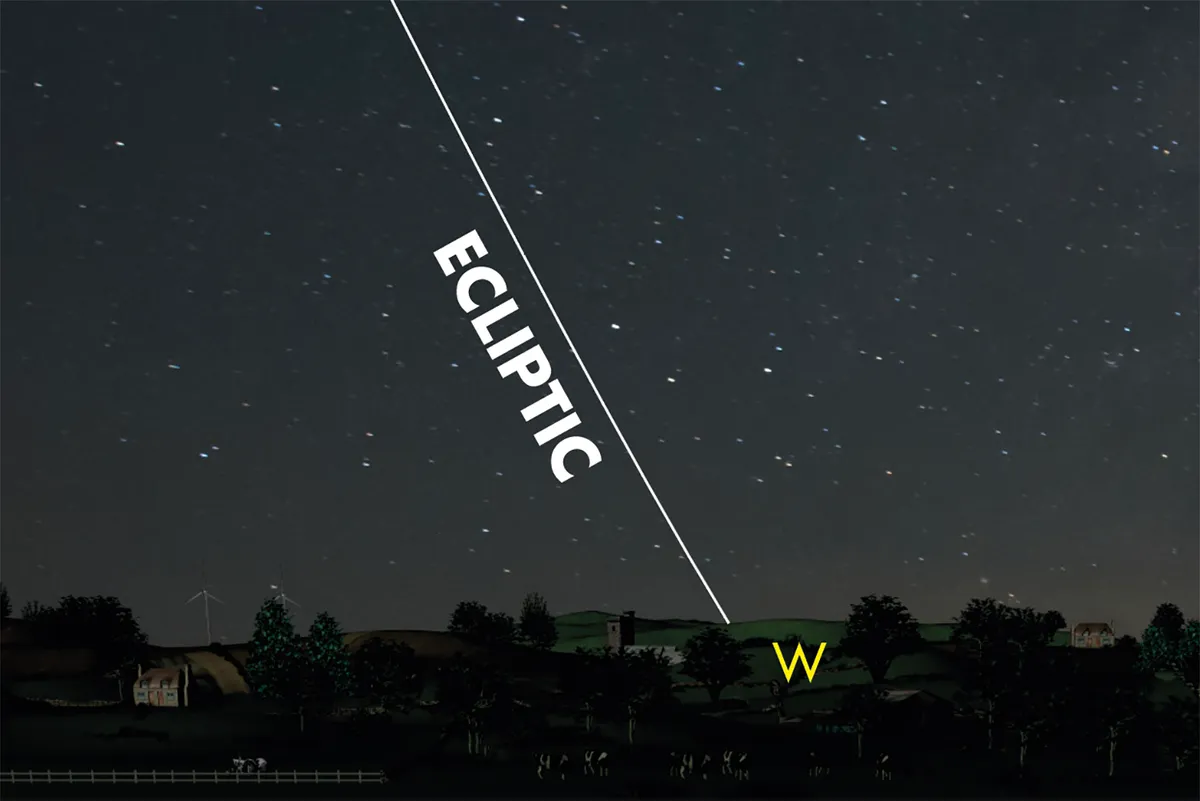

The first thing you need to do is find the ecliptic, the imaginary line that marks the path the Sun takes across the sky.

Since all of the Solar System’s major planets orbit the Sun in roughly the same plane, the ecliptic also marks the path of the planets.

You’ll always find all of the planets near that line.

Is it bright, but on the wrong side of the sky to the ecliptic? Then it can’t be a planet.

How to find the ecliptic

To find the ecliptic, carefully make a note of the Sun as it crosses the sky. Pay attention to where it rises and sets, and where it is during the day.

How high above the trees and the rooftops across the street is it, for example?

Once you have a feel for the path the Sun travels on during the day, use your imagination to try to map its path onto the night-time sky.

This is a good method to remember if you want to know how to find planets in the sky.

Keep an eye on the Moon, too. Its orbit around Earth tilts by about 5° compared to the ecliptic. That means the ecliptic is always within 5° of the Moon.

That’s about the width of three of your fingers held up at the end of your outstretched arm.

Finally, remember that the ecliptic does not remain in the same place year round.

The Sun gets higher in the sky during the summer months than it does in the winter.

Finding planets among stars

Once you know roughly where to look, you can work out which objects are planets.

You know how a small tree outside your window looks bigger than a larger tree on a distant hillside?

Planets look bigger than the much larger and much more distant stars.

This apparent size difference gives them a subtle disc shape, which often becomes easier to see the more you look for it.

Also, because their light comes to us from many points – not just one as starlight does – they usually don’t appear to twinkle like stars.

Many planets have distinct hues; in some cases, they can shine much brighter than any star.

Inferior planets

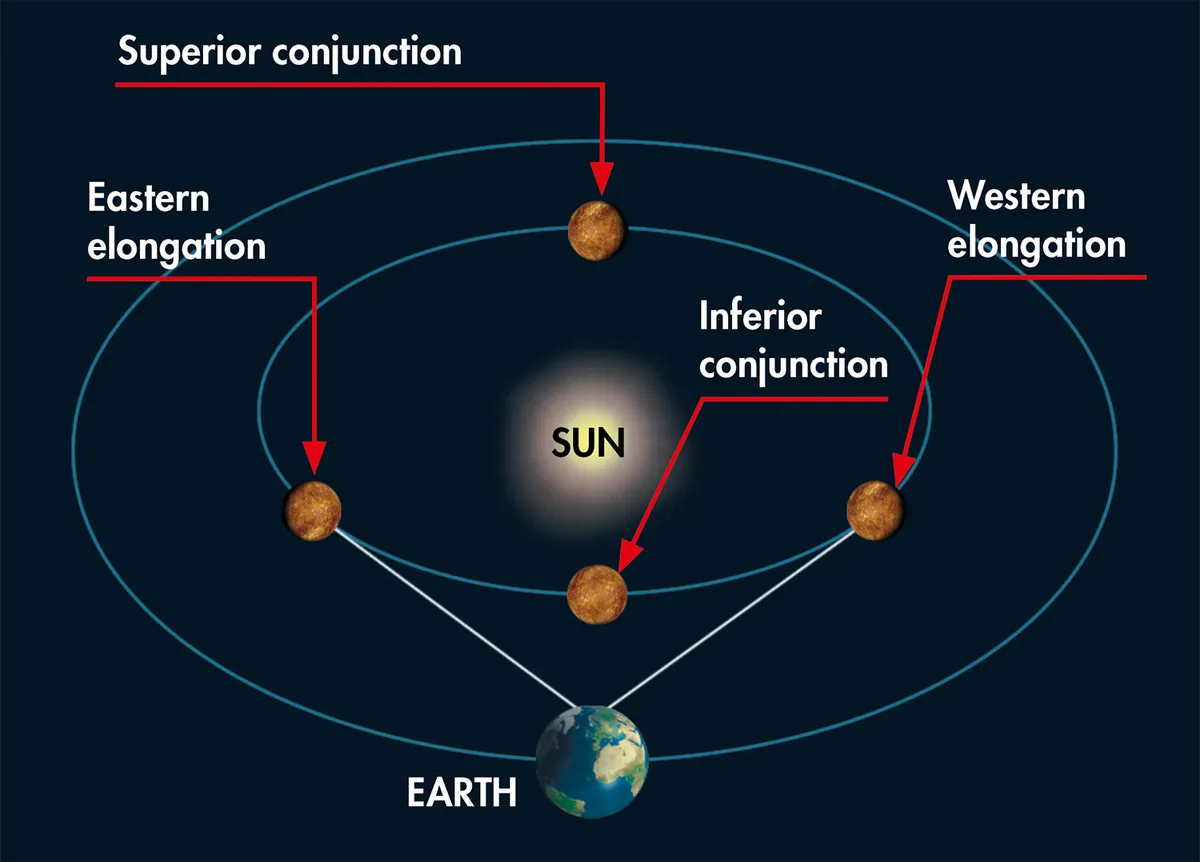

Mercury and Venus are inferior planets. That doesn’t mean they are uninteresting, only that they orbit closer to the Sun than Earth does.

From our perspective, they are always relatively close to the Sun in the sky.

Venus is never more than 47° away from it, which is about the width of five fists held out at arm’s length.

Mercury is closer still, never more than 28° away. This means they always rise shortly before the Sun or set shortly after it.

They’ll never soar high overhead late at night.

Since Mercury is very small, speedy, and close to the Sun, it’s particularly difficult to see.

It’s only visible for a short time, most often in glowing twilight, so you’ll need to be quick to spot it.

As challenging as it is, Mercury is bright enough to stand boldly against skies too bright for most stars.

If you see something yellowish staring back at you through the dawn or dusk, there’s a chance it could be Mercury.

Fellow inferior planet Venus is a stark contrast: a beautiful white colour and bright to the point of being unmistakable, its peak magnitude –4.4.

Superior planets

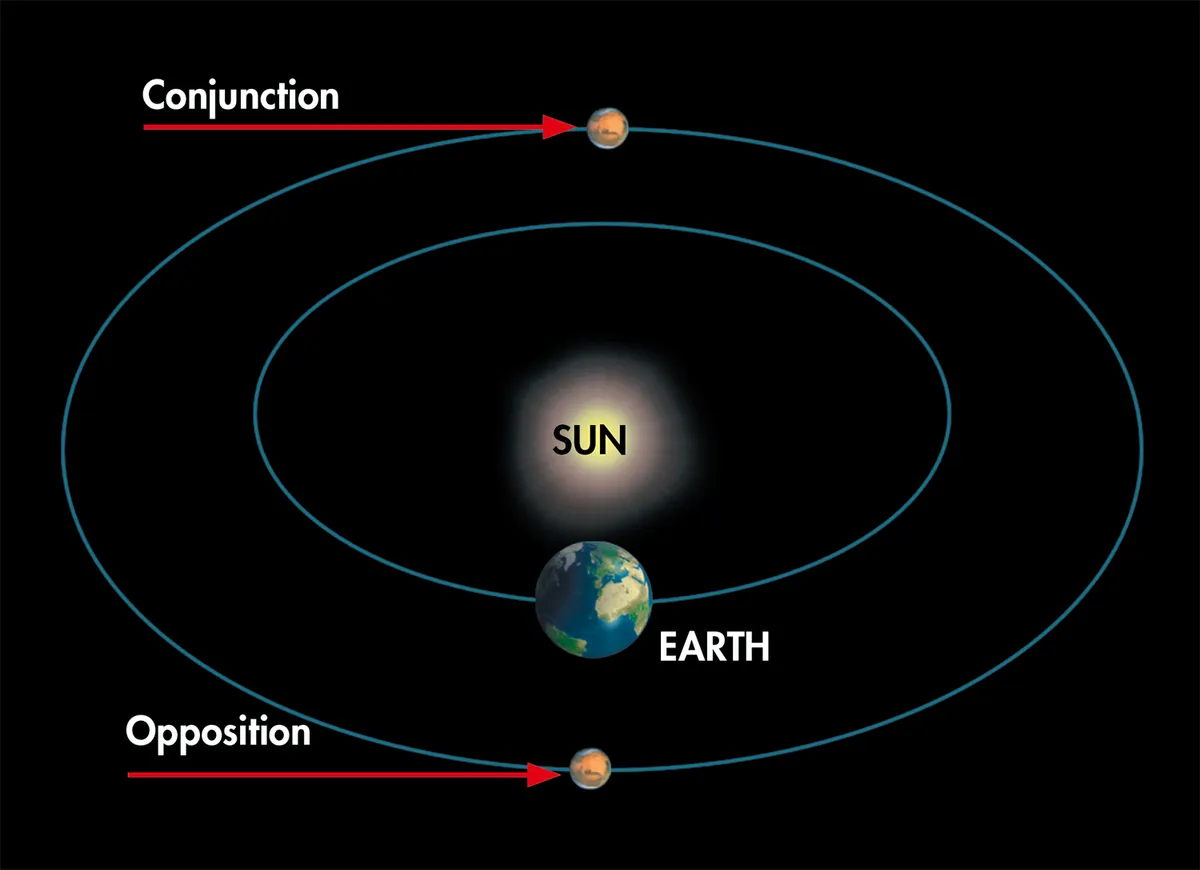

The superior planets are those that orbit farther from the Sun than Earth. They’re not ‘tied’ to the Sun from our perspective and can be anywhere along the ecliptic.

Red-orange Mars (peak magnitude –2.9), whitish-orange Jupiter (mag. –2.9), and understated yellow Saturn (mag. +4.3) are all visible to the naked eye.

Uranus and Neptune are not.

Uranus has a magnitude of mag. +5.7, hovering on the threshold of naked-eye visibility.

But you’d need impeccable eyesight and pristine skies to stand a chance of spotting it.

Neptune (mag. +7.8) is simply too dim to see without binoculars.

Potential problems

All of this said, there are times when finding the planets isn’t easy.

For one thing, even the superior planets may not be above the horizon all night long.

They can all disappear in the daylight sky, or may be stuck lingering just above the horizon.

From time to time, the planets are in conjunction with the Sun and are lost from view completely.

Nor do all planets shine at their peak magnitudes at all times – that depends on where they are in their orbits.

Superior planets tend to be brightest around opposition, when they are on the opposite side of the sky to the Sun.

With the inferior planets, the situation is more complex.

They are brightest in certain crescent phases, but set relatively soon after (or rise only briefly before) the Sun.

The gap between the Sun setting or rising and Mercury/Venus doing the same is greatest at the points of greatest elongation, but they are dimmer on these occasions.

Tips to remember

If you think you have found a planet, but you’re really not sure, keep an eye on it for a few nights.

Remember, the word planet comes from the Greek word for ‘wanderer’. All of the planets move, or wander, relative to the background stars.

From night to night, you’ll see them in a different position, but the stars themselves will stay fixed to each other.

Of course, this effect is more pronounced the closer the planet is to Earth.

Mars positively races across the sky compared to much more serene Saturn.

But with a little bit of practice, you’ll be able to find them.

This article originally appeared in the January 2018 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.