The current major meteor shower is the Geminid meteor shower, which peaks on 13–15 December.

And the Moon being a thin crescent below the horizon, that means conditions are perfect for seeing the peak of the best meteor shower of the year.

In this guide we'll reveal when the best meteor showers are, and the specific dates you should be observing them.

Get weekly stargazing advice by signing up to our e-newsletter and subscribing to our YouTube channel

Another factor affecting how many meteors you can expect to see is how prolific the meteor shower is, which is measured by its Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR).

This is the number of meteors you would see under perfect conditions, if the shower was coming from directly overhead.

In reality, the number you will see will be significantly less, closer to half.

There are many meteor shower big hitters like the Perseid meteor shower and Geminid meteor shower, while there are smaller, less-well-known ones like the Southern Delta Aquariid meteor shower.

The best meteor showers in 2025

- Lyrid meteor shower - 16–25 April, peak 22/23 April, ZHR of 15-20

- Perseid meteor shower - 17 July–24 August, peak 13 August, ZHR of 100–150

- Draconid meteor shower - 6–10 October, peak 7 October, ZHR of 5

- Orionid meteor shower - 2 October–7 November, peak 21/22 October, ZHR of 20

- Leonid meteor shower - 6–30 November, peak 17/18 November, ZHR of 10–15

- Geminid meteor shower - 7–17 December, peak 13/14 December, ZHR of 150

Annual meteor showers explained

The annual meteor showers are a permanent fixture on astronomers' and stargazers' calendars, mostly because they are regular, reliable, and they occur at the same time every year.

If you pick your moments and have a bit of patience, seeing a meteor shower is not difficult, requiring nothing more than a pair of eyes and something to record your results with.

You could even get family or friends to help you complete a scientific record of what you see.

Here we'll go through what a meteor shower is, how best to see a meteor and provide key dates as to when the major annual meteor showers take place, so you can determine whether a meteor shower is happening tonight or in the not-too-distant future.

What is a meteor?

The name meteor describes the phenomenon that occurs when a small particle – a meteoroid – enters Earth’s atmosphere and vaporises.

From the ground, the swift moving path of light that results is what’s known as a meteor trail, and this is why it's often referred to as a shooting star.

But an average trail is produced by a meteoroid similar in size to a grain of sand.

Larger meteoroids will produce bright trails, and a trail brighter than mag. –4 (similar to Venus) is known as a fireball.

Bright trails are often followed by a glowing column of ionised gas called a meteor train, which fades over time. Persistent trains may last for many seconds, becoming distorted by high altitude atmospheric winds.

What is a meteor shower?

Meteor showers are typically associated with comets, although a handful are linked with asteroids, such as 3200 Phaethon, the source of the Geminid meteor shower.

As a comet orbits the Sun, it releases dust. Over many returns, dust spreads around the orbit.

Earth passes through numerous dust streams annually and, when this happens, the number of trails seen increases.Peak activity occurs when we pass through the densest part of the stream.

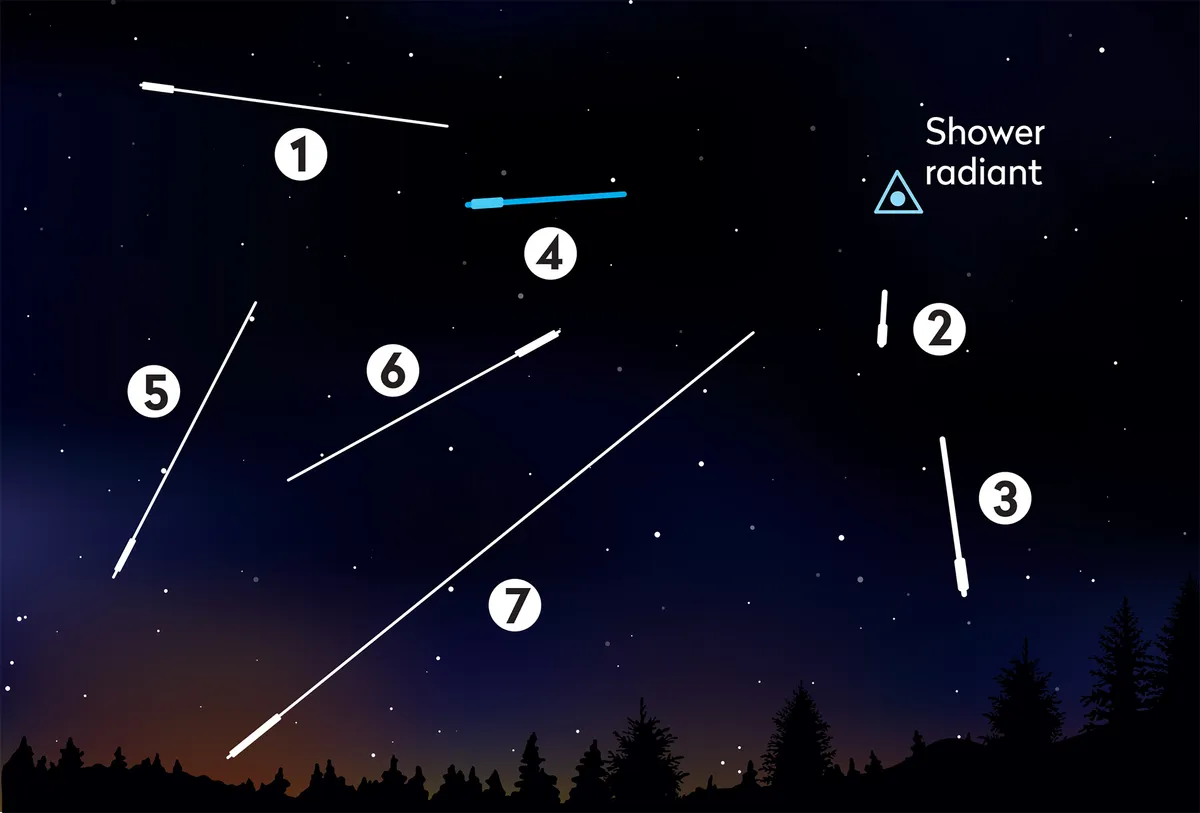

Perspective causes the incoming trails to emanate from a small area called the shower radiant, which slowly moves over the duration of the shower.

The constellation in which peak activity occurs gives its name to the shower. For example, the Perseid meteor shower shows peak activity when the radiant is in Perseus.

Our diagram below illustrates how to spot a meteor that belongs to a shower, as opposed to a sporadic meteor.

1-3 Shower trails

4Non-shower trail; wrong colour

5 Non-shower trail; doesn’t originate from the radiant

6 Non-shower trail; travelling in the wrong direction

7 Non-shower trail; too long for its proximity to the radiant

Zenithal Hourly Rate

Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) is a number often quoted as a description of how many meteors you will be able to see during a shower, but in actual fact this figure is used to normalise meteor shower rates for comparative purposes and isn’t intended to represent actual visual rates.

The term assumes a shower’s radiant is directly overhead (at the zenith), and that you are observing under a perfectly clear, dark sky with no visual obstructions.

Few, if any of these conditions will be met in reality, so the actual number of meteors seen is often significantly lower than the quoted ZHR.

Dates of the major meteor showers 2025

Our meteor shower calendar will reveal when the next annual meteor shower is taking place. 'Meteors per hour' signifies the zenithal hourly rate.

Perseid meteor shower

- Dates: 17 July-24 August

- Usual peak night: 12 August

- Meteors per hour: 110

- Radiant: Perseus

Orionid meteor shower

- Dates: 2 October-7 November

- Usual peak night: 21 October

- Meteors per hour: 20

- Radiant: Orion

Leonid meteor shower

- Dates: 6-30 November

- Usual peak night: 17-18 November

- ZHR: 15

- Radiant: Leo

Geminid meteor shower

- Dates: 4-17 December

- Usual peak night: 14 December

- Meteors per hour: 120

- Radiant: Gemini

Quadrantid meteor shower

- Dates: 28 Dec - 12 January

- Usual peak night: 3 January

- Meteors per hour: 110

- Radiant: Boötes

Lyrid meteor shower

- Dates: 14-30 April

- Usual peak night: 22 April

- Meteors per hour: 20

- Radiant: Lyra

Eta Aquarid meteor shower

- Dates: 19 April-28 May

- Usual peak night: 6 May

- Meteors per hour: 50

- Radiant: Eta Aquarius

How to identify a shower meteor

Not every meteor trail belongs to a currently active shower. Multiple showers may have overlapping activity and random or sporadic meteors may occur at any time.

Various checks can be applied, the most important of which is whether a trail appears to come from the shower’s radiant. If this isn’t the case, it’s definitely not a shower meteor.

Trail lengths also vary with distance from the radiant: those starting close appear short due to perspective.The trail's apparent length grows up to 90° from the radiant, after which it shortens again.

Trails further than 90° away start to converge to the shower’s anti-radiant. Long trails starting near the radiant are statistically unlikely to belong to a shower.

Trickier checks concern colour and speed. Colour, visible in brighter events or in photographs, will often be characteristic for a specific shower.

Similarly, trail speed varies between showers: a fast trail among a slow shower is unlikely to belong.

Sporadic meteors

Random meteors not associated with a particular shower may be seen at any time without warning. Known collectively as sporadic meteors (pictured, below), they can appear to come from any direction. Although sporadic meteors don’t belong to a cometary stream, many are related in terms of their source area in the sky.

Top tips for seeing a meteor shower

- Work out when the next meteor shower is occurring, and the peak activity

- Determine the shower's radiant: the area in the sky from which meteors will appear to emanate

- Find out whether the Moon will be bright and, if so, observe once its set

- Plan to travel to a dark location away from light pollution

- If going to a dark sky location is not an option, try standing in the shadow of a building

- Wrap up warm, even if observing during the summer

- Bring a reclining chair or sunlounger to avoid neck-ache

- Wait until after midnight, when you'll be on the night-side of Earth as it hits the meteor stream

- Leave around 30 minutes for your eyes to dark-adapt and you'll see more meteors

- Locate the radiant and try to spot meteors flying across the sky in the opposite direction

- Spend 30 minutes observing, then take a short break before continuing.

- Record your observations with friends: ask them to call-out when they see one, and note it down.

Spotting meteors during a shower is a pretty easy task to carry out, requiring nothing more than a pair of eyes and something to record your results with. You could even get family or friends to help you complete a scientific record of what you see.

As with all scientific recordings, there are guidelines to follow. Getting this right will elevate your observations and help advance our common knowledge of how specific meteor showers work.

Best of all, it doesn’t take a lot of effort to get to this level and the resulting observations may help predict future meteor activity.

How to stay comfortable during a meteor shower

Comfort is important when observing meteors and using a garden chair, preferably a recliner or sunbed, is recommended.Neck support for long watches is particularly important.

Aim to look up at 60°, where the atmospheric thickness isn’t great enough to reduce the brightness of trails, but remains sufficiently thick for the number of meteors to remain optimal.

It’s also important to wrap up warm, even if temperatures are fairly mild at the session’s start.

Ideally you would want to find a dark location, free from stray light. Give your eyes at least 20 minutes to adapt to the darkness before you start a watch.

Ideally, aim to observe for periods that are multiples of 30 minutes long, say 30, 60 or 90 minutes and pick a direction giving a clear unobstructed view.

The quiet lulls in activity that typically occur during meteor-viewing sessions are useful times to learn the constellations.

However, avoid looking down at charts for prolonged periods because this may cause you to miss trails.

How to record your meteor observations

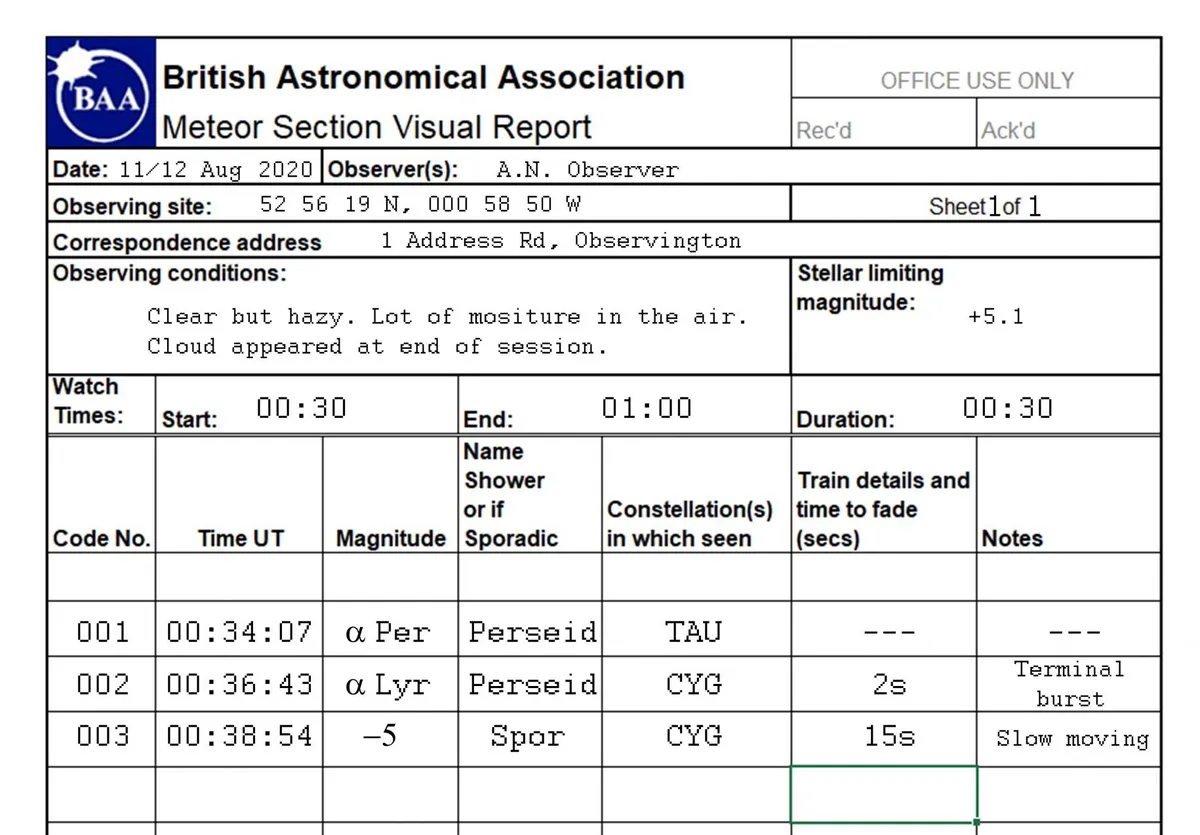

Get involved in real scientific observing by downloading a meteor reporting form from the British Astronomical Association (britastro.org) you can help with its national survey. On the form:

1 Date is normally stated as a double-date (say, 13/14 December 2020). This removes any ambiguity as it covers the evening to morning observed.

2 Observer(s) records the name(s) of anyone who contributes to the form.

3 Observing site identifies where you observed from, latitude and longitude being ideal. This can be obtained from a map or an online resource such as Google Earth.

4 Sheet of is used to ensure no loose sheets are missed, for example Sheet 2 of 4.

5 Correspondence address is where you can be contacted if the need should arise.

6 Observing conditions is intended as a general statement of the conditions throughout the watch. Augment with times if conditions vary greatly during the watch period.

7 Stellar limiting magnitude is a record of the faintest star which can be seen overhead. Again, augment with timed values if conditions vary greatly during the watch session.

8 The Start, End and, for convenience, Duration of the watch should also be recorded. Use UT throughout.

How to log each of your sightings

A Code No. is a sequential number used to identify a trail. If you’re in a group and performing central recording functions, it’s useful to leave a gap of say 5 or 10 between numbers so any trails reported out of sequence can be given the correct number even though they are in the wrong row.

The row sequence can later be corrected when the form is formally written up.

B Time UT indicates when the trail was seen. To the nearest minute is acceptable, although recording in higher time resolution is always useful.

C Magnitude can either be a magnitude estimate of the meteor trail or the name of the nearest star of equivalent brightness. The latter tends to remove observer bias.

It’s useful to have located a number of comparison stars of varying magnitudes before a session for this purpose.

D Name of shower or if sporadic is for the shower name the trail belongs to or whether it’s a sporadic meteor.

E Constellation(s) in which seen is used to describe the starting and ending constellation of the trail.

F Train details and time to fade is to record any special qualities about meteor trains. Time to fade records the number of seconds the train takes to become invisible to the naked eye.

It’s good practice to start counting in seconds in your head after any bright trail, just in case there’s a train visible afterwards.

G Notes is used to indicate any peculiarities about the trail. Examples would include ‘it exhibited a strong green colour’ or ‘meteor trail showed a terminal burst at the end’.

If you do manage to get out and do some successful meteor shower observing, let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com or via Facebook and Twitter.

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine but is regularly updated throughout the year.