As an inner planet, Mercury presents new and exciting challenges to planetary astronomers, and in this guide we'll show you the best times to see it, and how to observe it.

Due to its proximity to the Sun, extra care must be taken to observe Mercury safely, which adds to the challenge.

There are particular times that are best to observe elusive, mysterious Mercury.

You may want to wait, for example, until it's next to another planet in the sky, such as during a Jupiter Mercury conjunction.

Get ready to enjoy one of the Solar System’s unsung heroes.

For regular stargazing advice, sign up to receive the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter and listen to our weekly Star Diary podcast.

Mercury's orbit explained

The fastest and smallest planet in the Solar System, Mercury is named after the messenger of the Greek gods, renowned for speed. And time is certainly of the essence with this planet.

To observe Mercury, we need to understand how its position relative to the Sun affects its visibility.

Mercury is 0.4 astronomical units (AU) away from the Sun and orbits at speeds of up to 47km per second, compared to Earth’s relaxed pace of 30km per second.

When it reaches its closest point to the Sun, Mercury is at its fastest and it then slows down slightly the further away it gets.

As the innermost planet, it also has the shortest year, taking 88 Earth days to circle the Sun.

The gravitational influence of the Sun affects Mercury’s orbit in other ways too.

Mercury’s journey around the Sun is highly ‘eccentric’, or egg-shaped.

This means the distance between the two can vary from 46,000,000km to 69,000,000km.

But just because Mercury’s years are short, it doesn’t mean its days are. It rotates so slowly on its axis it completes one full rotation roughly every 59 Earth days.

When we consider the speed that Mercury travels versus its slovenly rotational rate, we realise it doesn’t experience conventional sunrises and sunsets to mark day and night times.

One ‘solar day’ (a full day–night cycle) on Mercury is 176 Earth days!

Another thing that makes Mercury unique is its lack of moons. Anything likely to be bound to the planet is instead attracted by the strong pull of its host star.

Mercury elongations and conjunctions

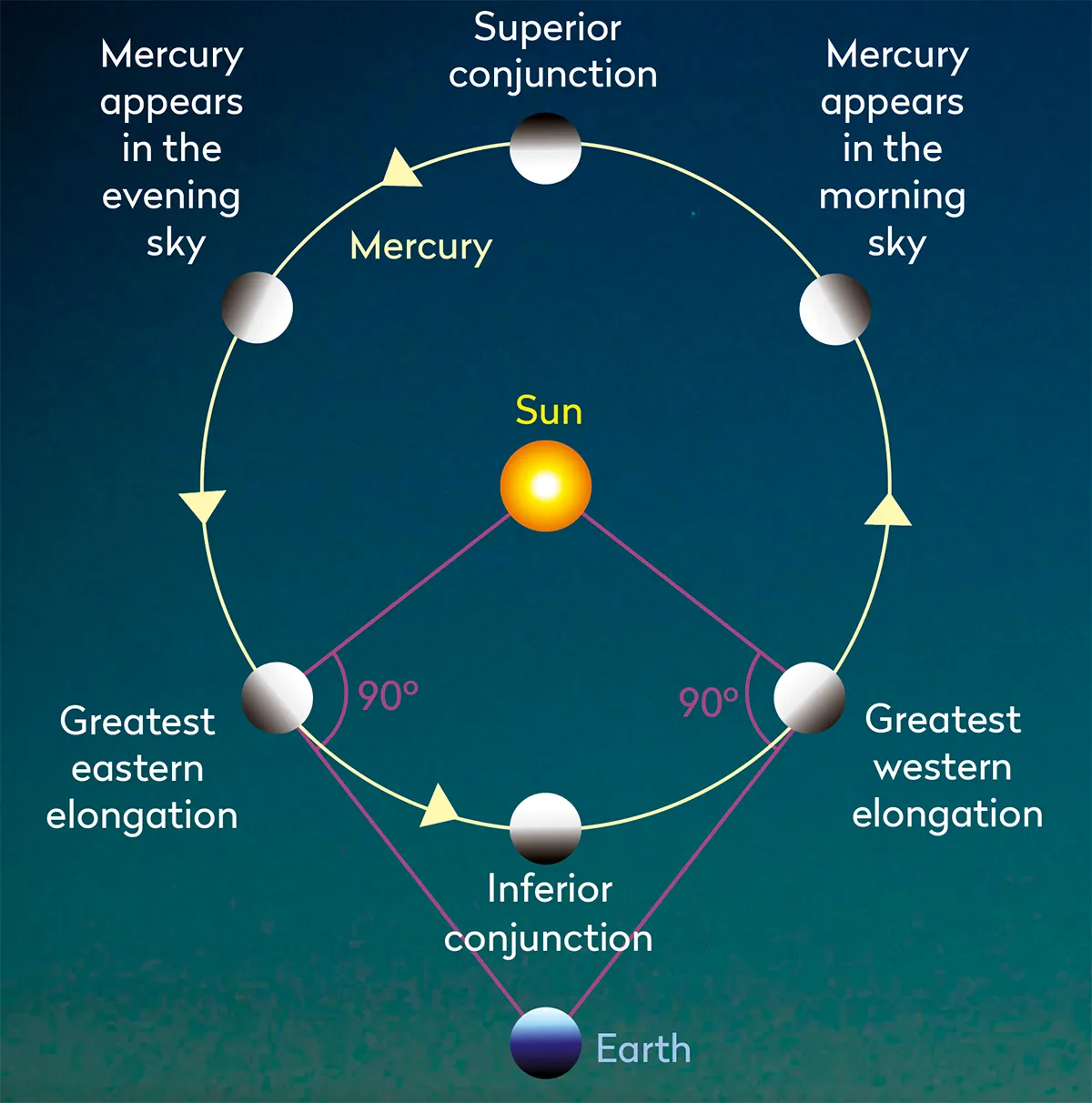

Because Mercury is the planet closest to the Sun, it always appears close by and is often swallowed by our home star’s glare.

Mercury’s appearances are therefore closely linked with our sunrise and sunsets, making it a morning or evening object, rather than something we can look for during later hours.

The best time to observe Mercury is during greatest elongation.

This is when Mercury is farthest from the Sun, so it is placed far either to the east or west side of it (known as eastern and western elongations, respectively).

The angular separation due to elongation can vary from roughly 20° to 28°, the equivalent of one handspan to three clenched fists next to each other, held at arm’s length.

When positioned at the eastern side of the Sun, Mercury appears in our evening skies; when at the western side it appears in early morning skies.

When it makes its evening appearances, the planet is seen above the western horizon shortly after sunset in twilight, and as a morning planet it appears in the east shortly before sunrise.

These elongation events mark Mercury’s best and safest observing periods. Because Mercury is closest to the Sun, elongations are regular and happen every 3–4 months.

It’s at this point that the planet will appear highest above the horizon, placing it at the best position to observe as it will be clear of light pollution and least affected by atmospheric seeing.

Mercury inferior and superior conjunctions

Inferior and superior conjunctions are specific to the inner planets, and mark times when we can’t observe Mercury.

- Inferior conjunction is when Mercury or Venus passes directly between Earth and the Sun, positioning them in front of the Sun at sunrise and sunset, so they're lost in its glare

- Superior conjunction is when Mercury of Venus is on the opposite side of the Sun to Earth, again making them unobservable

What to see when observing Mercury

So what can we observe when the time is right for Mercury? Despite its challenges, the planet can be appreciated with and without a telescope.

Naked eye

If viewed with the naked eye, Mercury tends to appear as a bright point object, similar in appearance to a star, with its magnitude varying from as bright as mag. –2.8 to a dim mag. +7, when it is only visible through binoculars or a telescope.

If close to the horizon, atmospheric turbulence might make it appear to ‘twinkle’ like a star.

However, if you take some time to study it unaided you will detect a subtle, rosy, golden tinge that singles it out from the starry background.

Mercury’s apparent diameter, depending on its distance from Earth, can range from 4.5 arcseconds at apogee to 12.9 arcseconds at perigee.

Telescope

A pair of low-powered binoculars will help you locate the planet, particularly at times when it is dimmer.

Because Mercury is often viewed against brighter skies, a telescope will help you locate it.

Again, you’ll want clear western or eastern horizons (depending on when you’re viewing).

With a 3-inch scope you’ll start to appreciate Mercury’s phases.

Although the planet is unobservable at its full phase during superior conjunction and at its new phase at inferior conjunction, even in the short windows of opportunity in between you will notice changes in its phases.

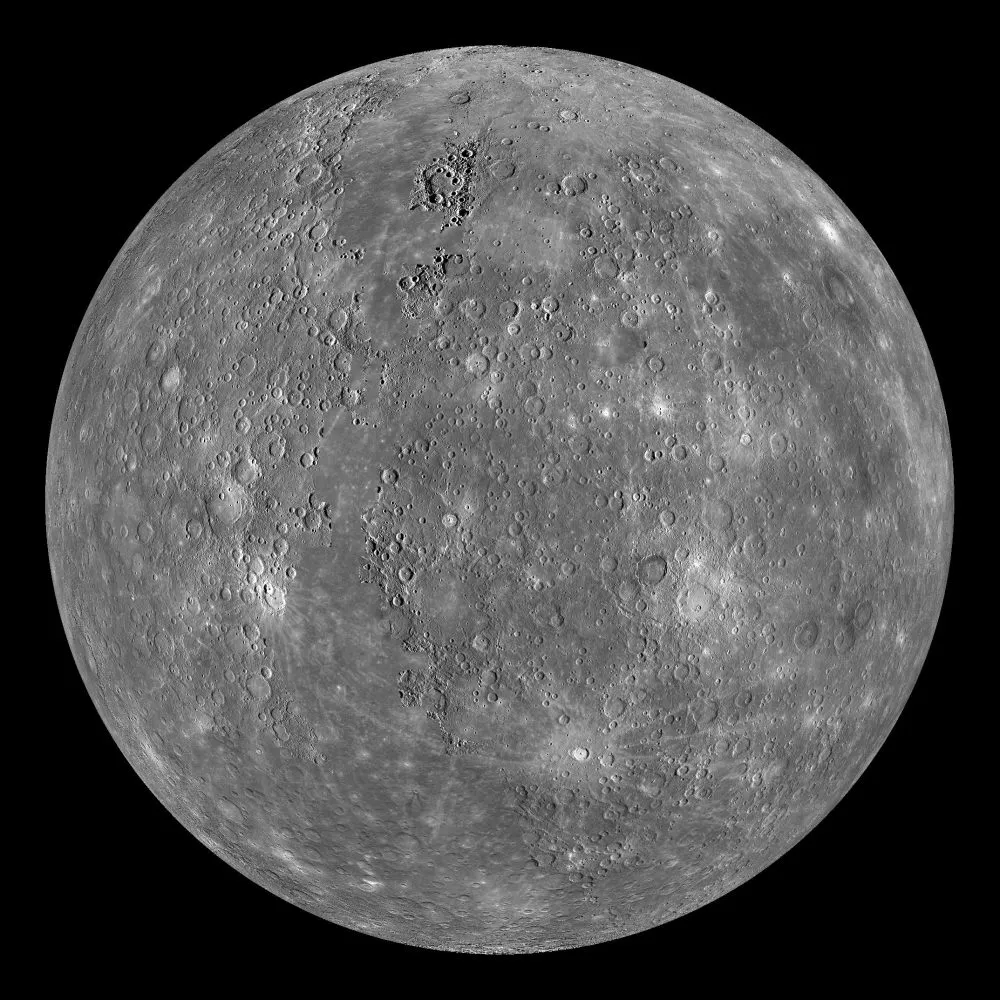

While we won’t see craters, on nights of exceptional seeing and minimal turbulence, we may discern some surface details with larger-aperture telescopes.

With all planetary astronomy, seeing conditions will greatly affect observations.

Therefore, providing it’s safe to do so, try to observe Mercury at its highest possible altitude, at a minimum of one hour outside of sunrise or sunset times.

A word on safety

Because it is so closely bound to our Sun, it is imperative when you observe Mercury to avoid the risk of viewing the Sun directly.

Never try to find Mercury in broad daylight or during conjunctions; aim instead for elongation events.

Ascertain the sunrise or sunset time on the day of observation and use a sky guide to establish the angular separation of Mercury from the Sun.

Ensure that the full disc of the Sun is behind the horizon at the time of viewing.

This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.