If you're new to astronomy, you might be wondering where to start. It can be daunting stepping out under the night sky for the first time with the intention of learning your way around the stars and constellations, looking out for planets and trying to get to know all about the phases of the Moon.

This can be especially difficult if you don't have any more experienced amateur astronomers to help, or maybe you're wondering whether you will be able to see anything at all without an expensive telescope (spoiler: you will!)

Beginners' books and guides can be a great introduction to astronomy, but nothing beats experience. The more you stargaze, the more you’ll learn. Here are some things you’ll become aware of in your first year of observing.

For more advice, read our guides on how to stargaze and astronomy for beginners, or our pick of the best telescopes for beginners

1

There’s an ‘observing window’ each month

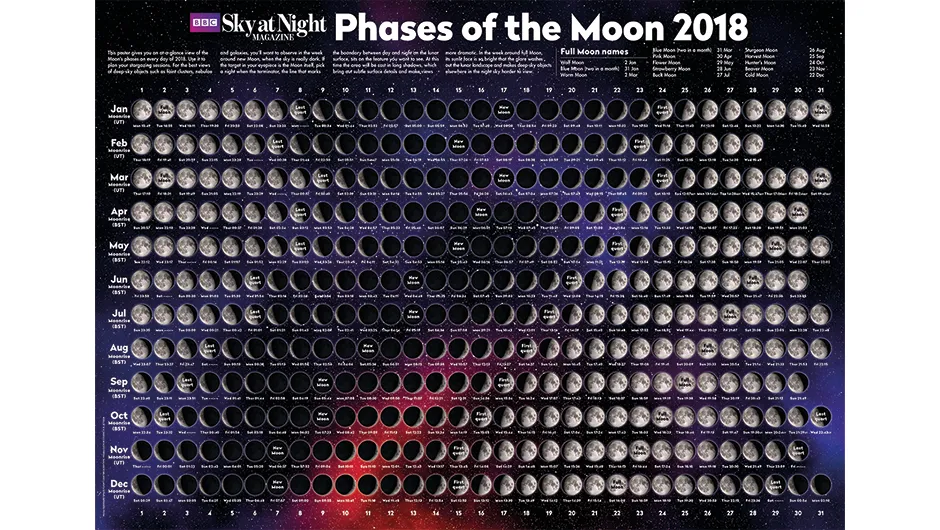

Bright moonlight is a big light polluter, so it pays to keep track of the Moon’s movements and phases.From about four days after new Moon, our lunar neighbour grows from a slim crescent to a bright orb that blots out stars right up until about six days after full Moon, after which it doesn’t rise until the early hours.

As a result, there’s a window of about 12 days surrounding new Moon when you’re assured of a dark Moonless sky that is ideal for stargazing.

HOW TO FIND IT: Get a poster of Moon phases or find the info online and be sure to plan any stargazing activities around new Moon. Our sign up to our newsletter and get the lunar phases delivered every week to your email inbox.

2

Find that unmissable ‘smudge’ in the winter night sky

Does a bright blob always catch your eye when you’re out stargazing in autumn and winter? It’s almost certainly the Pleiades (M45), a cluster of stars 440 lightyears distant that’s also called the Seven Sisters.

It’s a young cluster of stars just 100 million years old.Even with the naked eye you should be able to make out about five or six of its stars forming the shape of a mini Plough.

HOW TO SEE IT: Low in the east at dusk in November, the Pleiades is a gem of the winter night sky. Part of the constellation of Taurus, it’s visible every night until May.

3

Night vision makes stargazing much easier

As your eyes grow accustomed to darkness, your pupils dilate and allow in more light. It’s why patience is so important when stargazing.

HOW TO GET IT: Keep away from all bright lights for at least 20 minutes (yes, that absolutely does include your smartphone!) and, if you do need to use illumination in the field (to read or make notes), use a dim, red light.

4

Observing the full Moon is best done at moonrise

Most beginners presume that the best time to observe the Moon is when it’s high in the night sky, but at that point it’s way too bright.

Instead, find out the exact time of moonrise on the night of the full Moon and watch our satellite appear on the horizon during dusk in a gorgeous pale orange colour.

HOW TO SEE IT: Get somewhere reasonably high with a clear view of the eastern horizon at dusk on the night of the full Moon.

- Find out more in our guide How to observe the Moon.

5

Light pollution can be helpful

A dark sky full of stars is an incredible sight, but light pollution isn’t always a bad thing.When you’re trying to learn the shapes made by the main, bright stars of constellations, the fact that the background of thousands of stars is ‘missing’ because of urban lighting can actually be useful.

So for now learn to live with light pollution. You’ll grow to hate it soon enough.

HOW TO AVOID IT: If you’re stargazing from an urban area, stand in the shadow of a building where there are no streetlights or other lights directly in your field of view.

- Find out more in our guide to fighting light pollution.

6

The changing sky

As Earth orbits the Sun, the positions of stars change slightly, rising in the east four minutes earlier each day.Consequently, the entire night sky appears to shift forwards by four minutes each night.

You most likely won’t notice this if you spend a few consecutive nights stargazing at the same time of night, but over the course of a month it’s a two-hour difference.So stars rising at 10pm in October can be seen at 8pm by November.

HOW TO SEE IT: Look at the sky at a completely different time of night than you’re used to.In fact, if you stargaze at 2am in October you’re actually looking at the same night sky that will be visible at 8pm in February.So it doesn’t actually take a year to observe all the seasonal stars and constellations, after all.

7

Pick your meteor-spotting sessions carefully

The thought of shooting stars ‘raining down’ is enough to excite any stargazer, but in practice many of the minor meteor showers can be a let-down.

Firstly, it’s quite often cloudy on ‘peak’ night. Secondly, the number of meteors you can see in an hour of peak activity is changeable.

Thirdly, strong moonlight and light pollution can completely wipe out most of them.

HOW TO SEE THEM: Minor meteor showers such as the Lyrid meteor shower, Orionids and Leonids produce at most 10-20 shooting stars per hour, and of those far fewer are likely to be easily visible.

Their peak nights are best treated as great nights to go general stargazing, with the added bonus of seeing a few shooting stars.

Only the year’s major meteor showers – the Perseid meteor shower in August and the Geminid meteor shower in December – are worth a dedicated trip to a dark sky site.

- Find out when the next meteor shower is taking place

8

The Milky Way is only overhead in summer

That bright core of our Galaxy that you always see in photographs is only visible overhead during summer, when Earth is facing towards the centre of the Milky Way about 75,000 lightyears away.In winter, we’re looking outward into deep space.

HOW TO SEE IT: Look southeast after dusk in June, July and August from a dark sky site.

- Find out more in our guide on how to see the Milky Way.

9

Some stars are visible all year long

Earth’s northerly axis points roughly to Polaris, the North Star, which appears stationary in the night sky as all other stars in the northern sky appear to revolve around it.

The two close star patterns of the Plough and Cassiopeia are thus always visible to stargazers in the northern hemisphere.In the rest of the northern hemisphere sky, stars rise in the east and set in the west.

Further south, there’s a whole hemisphere of stars and constellations that we, at our northerly altitude, never get to see.

HOW TO SEE IT: Look north at any time of year to find Polaris between the Plough and Cassiopeia (though in autumn and spring they can get lost on the horizon).

If you stargaze at the same time of night throughout the year, you’ll see that stars and constellations are each visible for six months, during which they shift slowly from east to west.

For the rest of the year, they’re only ‘up’ during daylight.

10

Satellites are a regular sight

You don’t have to stargaze for long before you see a satellite whizz across the night sky.During an hour’s stargazing you can see dozens, all of which are over 6m in length and in a low-Earth orbit around 160-640km up.

You’re looking at reflected sunlight, so it’s a constant light unlike the flashes from aircraft.

HOW TO SEE THEM: You’ll see more satellites just after dusk and just before dawn, though in the UK summer the Sun doesn’t sink as far below the horizon, so satellites can be seen all night.

11

Travel north for a better chance of seeing aurora

The result of electrically charged particles ejected from the Sun interacting with Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere, the Northern Lights, or Aurora Borealis, move in an oval shape around the Arctic Circle on the night-side of Earth.

These aurorae wax and wane from north to south, so they can occasionally be seen from Scotland, northern England and north Wales.

HOW TO SEE IT: If you want to maximise your chances, take a trip to a place within the latitudes of 64º and 70º north between October and March: places such as Iceland, northern Norway, Lapland in Finland or Sweden.

However, if there are huge sunspots, stargazers can sometimes see a green glow on the northern horizon from the UK.The best places are Scotland’s northern coast and Orkney (both at 59° north), and the Shetland Islands (60.5° north).

12

Your peripheral vision is powerful

The human eye’s peripheral vision is very sensitive to brightness, so look slightly to the right of a star cluster, nebula or galaxy to see its glow.Conversely, when observing a star or planet, look directly at it to see colour.

HOW TO SEE IT: Look just above the Pleiades for a good lesson in this ‘averted vision’ technique, which works just as well with the Orion Nebula (M42), the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) and any star cluster. For more on this, read our guide on how to see the Andromeda Galaxy.

13

Planets are very easy to find

The Sun and the planets appear to move across the sky on roughly the same path, which reveals that all the planets in the Solar System orbit the Sun in a virtually flat disc.

This is called the ecliptic, and it’s here that you’ll find the planets close by.The Moon also roughly follows the ecliptic.

HOW TO SEE IT: The ecliptic stretches from the point on the eastern horizon where the sun rises to where it sets in the west; look to the south after dark and trace the position of the planets.Since Mercury and Venus are inner planets, they are only visible in the west soon after dusk, or before dawn.

- Find out more in our guide on how to find the planets in the night sky.

14

Spot the space station moving west to east

If you see a bright light rise roughly in the west, get extremely bright and then disappear in the eastern sky, you probably just saw the International Space Station (ISS) or, rather, its huge solar panels reflecting sunlight.

The ISS orbits Earth 16 times each day at 27,600km per hour, which is around 8km per second.

HOW TO SEE IT: You can only see the ISS when it’s crossing overhead just after dusk and just before dawn.If you do see it soon after dark, wait 92 minutes and you’ll probably see it again.

- Find out more with our guide on how to see the International Space Station in the night sky.