If you’re a newcomer to the wonderful hobby of astronomy, your first time under a clear sky can be an overwhelming experience.

How will you ever find your way around this vast number of stars?

Fortunately, there’s a tried and tested method, developed over millennia, to turn this bewildering confusion of bright dots into a familiar recreation ground, and which works in bright and dark skies alike.

It’s called star-hopping.

What we do is make easily identifiable patterns (called asterisms) from the brightest stars and use these as jumping-off points to locate our desired target objects

And we estimate directions in relation to other stars – for example, “towards that bright yellowish star”.

Estimating distances works in much the same way – for example “a third of the way from the lower star to the upper one”

Or a proportion of the field of view of your binoculars or telescope.

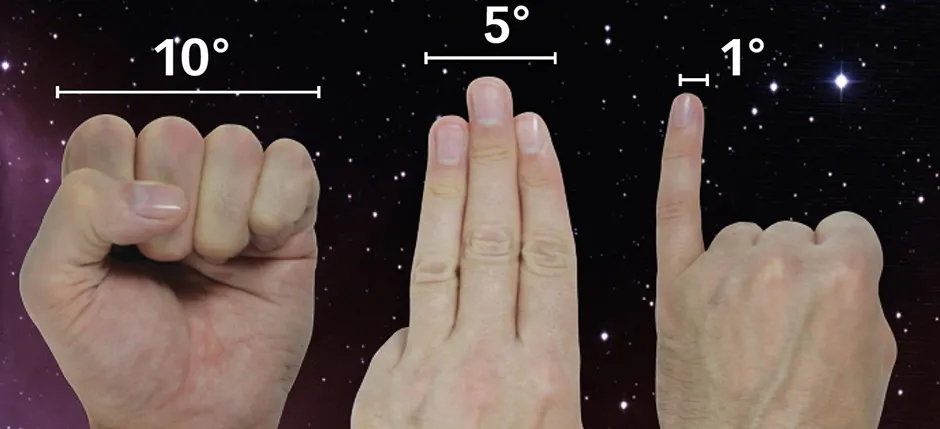

Alternatively, if you stretch out your arm, you can use the distance covered by your fist or handspan to measure out the distance.

Most of us are more or less similarly proportioned for this purpose.

Let’s look at four star-hops to help test your skills.

4 easy star-hops

Polaris, the North Star

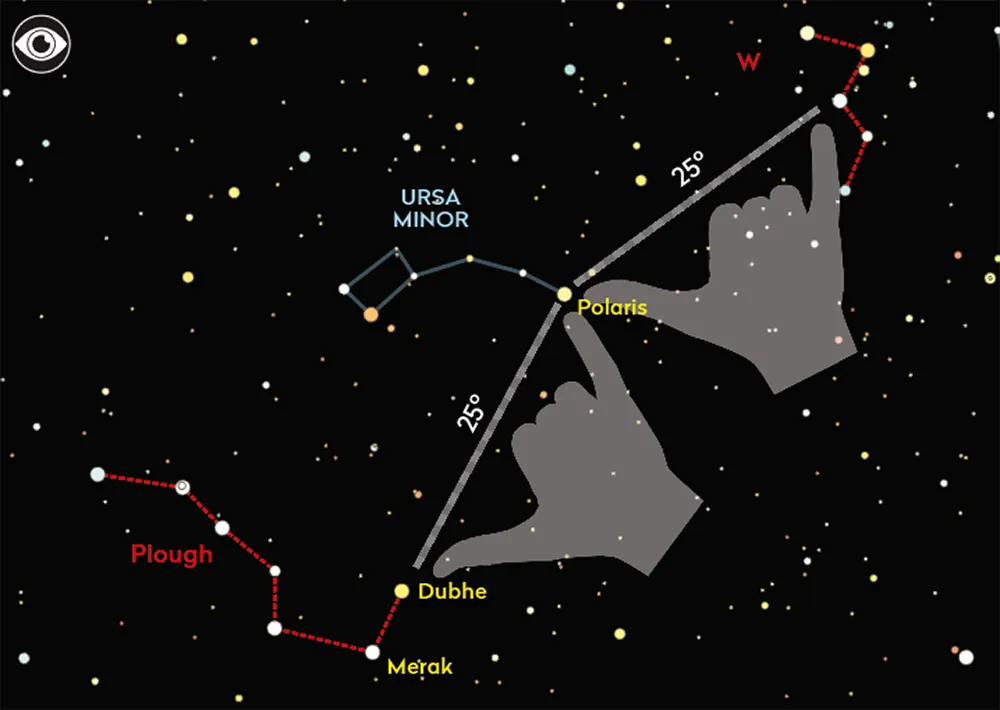

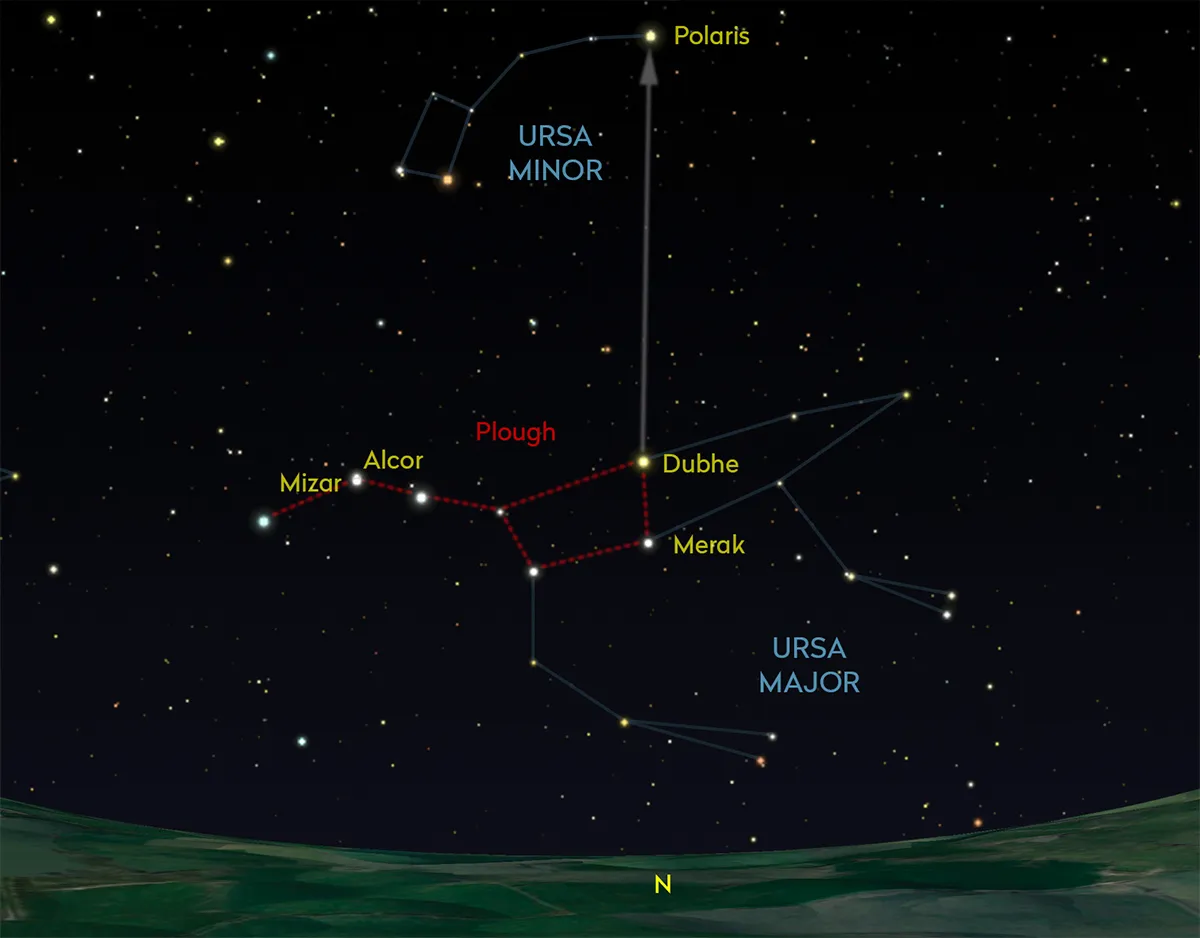

Polaris is crucial in astronomy, because it marks the position of the North Celestial Pole.

This is, the point around which the northern sky seems to revolve, and which is above the north point on the horizon – so that’s where we’ll begin.

We’ll use ‘the pointers’, Merak and Dubhe, in the Plough asterism of Ursa Major.

These point directly to the pole star, Polaris, which is slightly more than a hand-span from Dubhe.

Or, if you prefer, about five times the distance between Merak and Dubhe.

Sometimes, during autumn evenings for example, the Plough may be close to the horizon and concealed by trees or buildings.

In that case, the W-shaped constellation of Cassiopeia will be high in the sky and we can use that instead.

For help with this, use our guide on how to find the North Star.

Kemble's Cascade

Finding Kemble’s Cascade in Camelopardalis with binoculars requires a long star-hop, as there are no nearby bright stars.

Find Caph and Segin at either end of the ‘W’ shape of Cassiopeia.

Use the little finger and index finger of one hand to measure the distance between them.

Then, without changing the distance between your fingers, locate the point in the sky that’s the same distance the other side of Segin in a straight line from Segin and Caph.

Keeping your eyes fixed on this point, raise your binoculars and you should see a straight line of eighth and ninth-magnitude stars with a bright mag. +5.0 one in the middle.

On autumn evenings it’s almost vertical, resembling a ribbon waterfall cascading into the ‘splash-pool’ of the open cluster NGC 1502.

Andromeda Galaxy

The easiest way to find the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, is a two-part star-hop.

The first hop locates the star mag. +2.1 Mirach in the constellation of Andromeda, from which we do a second hop.

Locate the ’V’ of stars made by Caph, Schedar and Gamma Cassiopeiae.

Follow the arrow these make to Mirach, around a hand-span away.

Now locate Mirach in binoculars: it’s distinctly yellow, so is easy to identify.

Put it near the southeast edge of your field of view (near the bottom during autumn evenings) and look for the white, mag. +3.9 Mu Andromedae near the other side.

Now put Mu where Mirach was and you’ll see a fuzzy patch where Mu was.

This is the light that has arrived in your eyes 2.5 million years after it left the Andromeda Galaxy.

Globular cluster M56

At mag. +8.4 and only 5 arcminutes in diameter, globular cluster M56 is a little faint and small for binoculars, so we’ll change to a telescope.

To find it, first identify mag. +3.1 Albireo, the head of Cygnus, the Swan, and mag. + 3.3 Sulafat in Lyra. M56 lies directly between them, 4.5° from Sulafat.

If your telescope has a finderscope, you can relate this distance to its field of view (a typical 6x30 finder is 7°).

Otherwise, you can use the apparent width of your three middle fingers, which is roughly the same as 4.5°.

With a low-power eyepiece in the telescope, use your finder to put you in approximately the right position.

You should be able to see M56 looking like a defocused star in the telescope eyepiece.

Centre it and swap to a higher-power eyepiece to get more detail.

This guide originally appeared in the September 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.