Astronomers everywhere will welcome 2022 with open arms, ready to embrace a new astronomical calendar bursting with comets, occultations, meteor showers and supermoons.

Many of these exciting events will be visible with the naked eye or a pair of binoculars, and there will also be occasions when a telescope is needed.

If your New Year’s resolution is to take up stargazing, then this guide will help you get started.

You will be amazed at what you can see with just a little bit of time, some basic research (such as your location and the direction you are facing) and patience.

Remember, stargazing is for everyone, so let’s get stuck in and savour everything that 2022 has to offer.

For more stargazing advice, read our top tips on how to stargaze, our month-by-month guide to observing the planets or keep up with our monthly Star Diary podcast.

You can also sign up to the BBC Sky at Night Magazine e-newsletter for regular astronomy advice delivered directly to your email inbox.

January - March 2022

We begin the year when the nights are still very cold, so grab a blanket, a hot drink and step outside into the crisp cold air to enjoy the annual Quadrantid meteor shower.

Kicking the year off, the meteor shower takes place on the night of 3 January and into the morning of 4 January.

While not the most spectacular of showers, this year’s display should be worthwhile because there will be no bright Moon to wash it out.

Look to the northeast to find the constellation of Boötes, the Herdsman, near the Plough asterism; it’s here you will find the radiant, the location in the sky from which the meteors appear to originate.

There are planets-a-plenty throughout 2022 and in February, Uranus – the seventh planet from the Sun – will be visible in the night sky above the first-quarter Moon on the seventh day of the month.

Shining at mag. +5.7, and with the bright waxing Moon in view, you will have to reach for your binoculars to see this icy planet. 10x50 binoculars will do, or a small telescope with an aperture of 3 inches and a magnification of x100.

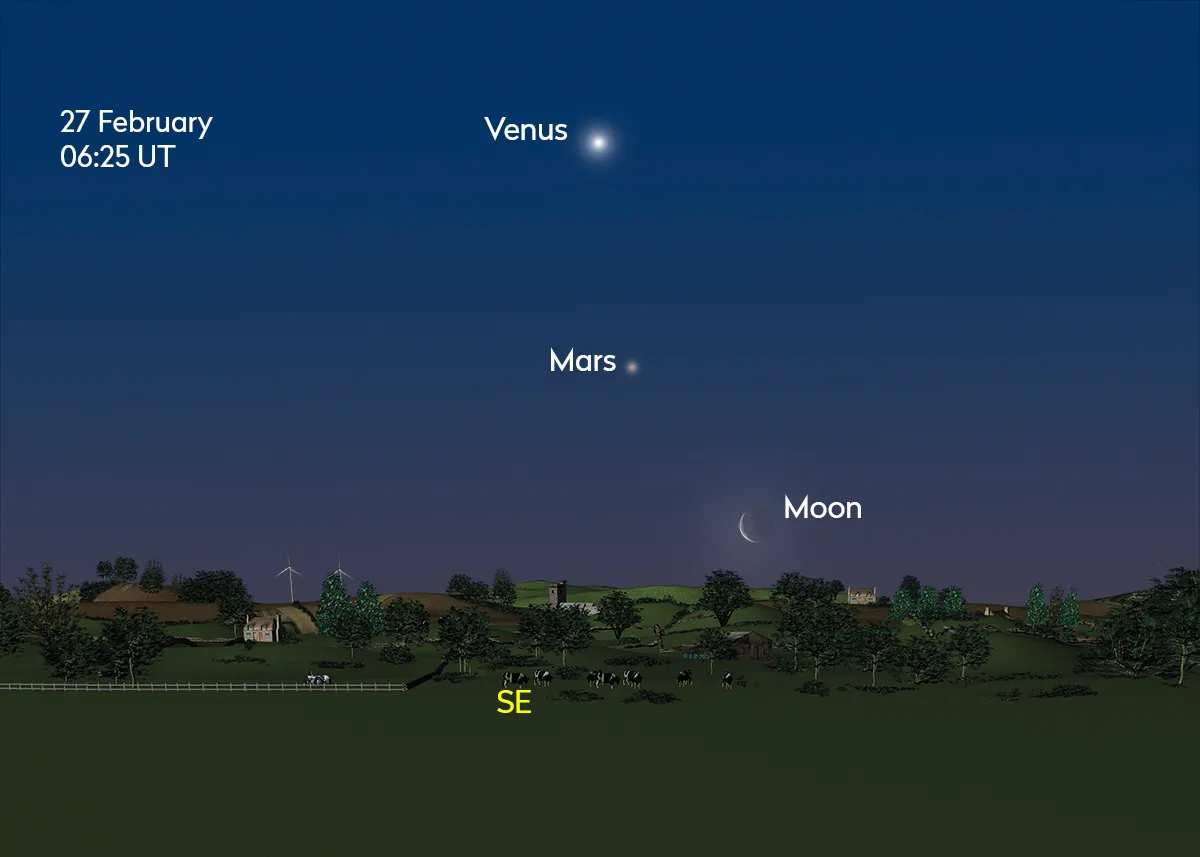

Venus is the morning ‘star’ throughout most of the year. Easy to identify because of its exceptionally bright appearance, the planet closest to us forms a dazzling conjunction with Mars on the morning of 27 February.

If you can locate the waning crescent Moon hanging low in the southeast, then look to its left and you will easily see Venus shining brightly above Mars.

Venus is at its best and brightest in the early mornings throughout the first half of March, and worth getting out of bed for.

The Sun starts rising earlier now and it will soon be time to wave goodbye to those long winter observing sessions that astronomers thrive on.

The spring equinox on 20 March marks the beginning of astronomical spring in the Northern Hemisphere.

A week later, on 27 March, British Summer Time (BST) begins so remember to put your clocks forward. The morning will now have one hour less of daylight and the evening one hour more.

April - June 2022

Mercury is the closest planet to orbit the Sun, which means it is quite an elusive target to spot. We only really see it when it appears at its furthest point, either east or west of the Sun.

The Solar System’s smallest planet puts on its best show of the year appearing above the western horizon not long after sunset on 10 April and it will be visible until the end of the month. You will have to be quick, though, as it doesn’t hang around for long.

You should see the planet with your naked eye or through binoculars, but remember to keep safe and only use any equipment with lenses once the Sun has fully set.

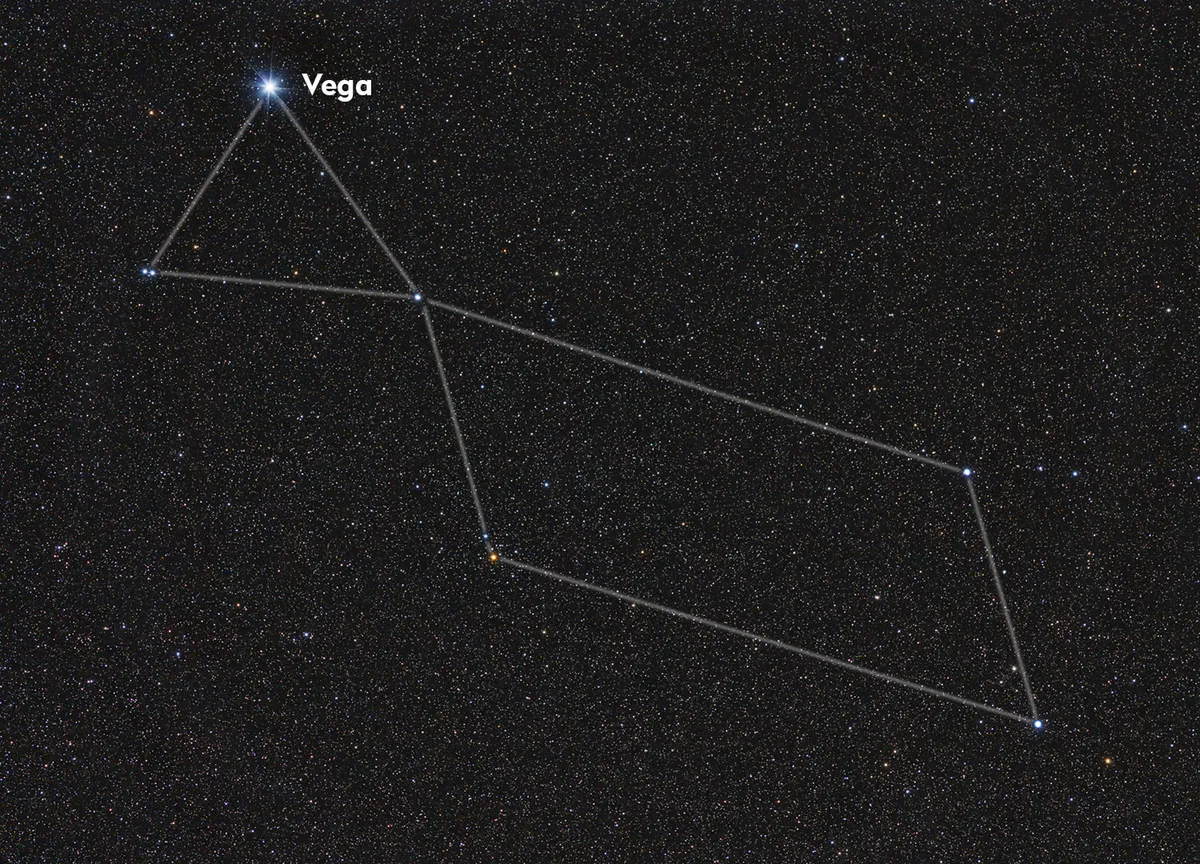

On 22 April, we have the peak of the Lyrid meteor shower. Thanks to the Moon rising after 03.00 BST (02:00 UT), the sky will be favourable and the view should be spectacular.

Set up on the night of 21 April and look towards the constellation of Lyra, the Lyre, rising in the northeast after 22:00 BST (21:00 UT) to see these meteors, which are caused by debris from Comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher.

You don’t have to wait long for the next meteor shower, but this one will take more effort to see.

On the morning of 6 May, the Eta Aquariids will produce around one meteor per minute, but the shower will only be visible for a few hours because the position of its radiant is close to the horizon.

If you saw Halley’s Comet in 1986 then you will be intrigued to know that these meteors originate from material left behind by that object.

Find a location with a clear horizon and look to the east from around 03.30 BST (02:30 UT) until sunrise.

Locate the constellation of Aquarius, the Water-Bearer, and enjoy the show!

If you are on social media and a member of an astronomical group, you will be aware of the excitement when the season of noctilucent clouds (NLCs) begins. You won’t need any equipment to see this ethereal silvery blue phenomenon.

NLCs will only appear on a clear summer’s night; they are cirrus-like clouds of ice that are in the mesosphere.

Due to their height, they are illuminated by the Sun after it has sunk below the local horizon. Look to the northern horizon in twilight to spot these beautiful clouds.

July - September 2022

The year ahead brings two ‘supermoons’. If you are unfamiliar with the term, a supermoon, or perigee Moon, refers to a full Moon that occurs around the closest point in its orbit to Earth – for example, around 357,264km away on 13 July.

On this date we can look forward to a supermoon that will be 30% brighter than usual and appear 14% larger.

If you plan on looking at it through a telescope, then make sure you use a Moon filter to reduce the bright glare; it’ll make viewing our

natural naighbour much more pleasurable.

The eagerly awaited Perseid meteor shower reaches its maximum on 12–13 August, when between 100–150 meteors can be seen per hour.

This is normally a highlight for keen stargazers, but sadly this year the shower will be washed out by a bright Moon one day past its full phase.

Don’t be disheartened; it is still worth getting outside to try and catch a glimpse of some of the brighter meteors, and of course to look at the Moon!

In September the planets will delight observers, including a rare occultation of the Moon and Uranus on 14 September.

In simple terms, an occultation is when one object passes in front of another, obscuring it from view.

The lunar occultation will take place around 22.30 BST (21:30 UT). Expect the event to take around 50 minutes, when Uranus disappears behind the Moon and then reappears.

A pair of binoculars or a telescope will be needed because 77% of the Moon will still be illuminated. If you miss this event, read on: you will have a second chance in December!

October - December 2022

As the nights draw in once more, astronomers will await the longer observing sessions ahead.

October brings the Orionid meteor shower, which takes place on the night of 21 October and morning of 22 October.

To locate the radiant, look for the constellation Orion, the Hunter, as it rises in the east after 22.00 BST (21:00 UT).

Meanwhile, the Taurid meteor shower, also know as the ‘Halloween Fireballs’, is visible from the end of October to the start of December.

You may have experienced a solar eclipse or lunar eclipse, partial or full, but if you haven’t, you will get a chance on 25 October when the UK will witness a partial solar eclipse.

The Moon will creep across the Sun around 10.00 BST (09:00 UT), obscuring it by about 15% and then vanishing from view at 11.45 BST (10:45 UT). Get some eclipse glasses now!

Over the next two months, Uranus hits the astronomical headlines again. On 9 November it will be at opposition, when it lies opposite the Sun and is at its closest to Earth. Use binoculars or a telescope to observe the bright planet in Aries.

On 5 December we are treated to a second occultation of the Moon and Uranus.

Lasting about half an hour, from 16:50 UT to 17:20 UT, the Moon will hide the planet from view just as it did back in September, so get your binoculars and telescopes ready.

But that’s not all for occultations, as it’s Mars’s turn to disappear behind the Moon on 8 December at 04:57 UT, reappearing at 05:58 UT.

On 21 December we celebrate the winter solstice when the Northern Hemisphere is at its maximum tilt away from the Sun, and our nearest star will be at its lowest daily maximum elevation in the sky.

As the Sun sets on Christmas day, a thin sliver of the Moon will be visible with Venus and Mercury hanging low in the southwestern sky – making a perfect and peaceful end to the year.

Comets in 2022

The delight of seeing Comet NEOWISE proved there is nothing quite like seeing a naked-eye comet. But, as we look forward to observing 2022’s best comets, remember just how unpredictable they can be.

C/2021 A1 Leonard reaches perihelion in January 2022, but it makes its closest approach to Earth on 12 December 2021. A1 Leonard may become a naked-eye comet, although it will be best seen through binoculars.

Locate Arcturus (Alpha (α) Boötis) in the constellation of Boötes, the Herdsman, before sunrise and after sunset to observe.

67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko, 4P/Faye and C/2019 L3 Atlas have been visible throughout the past year and can be found located around the constellation of Gemini, the Twins, at the end of 2021. They will be fading but a telescope will enhance your observations.

On 20 January, Comet 19P/Borrelly will be at its brightest, around 8th magnitude. Use binoculars or a telescope to see it in the evening in the south by Theta (θ) Ceti in Cetus, the Sea Monster.

C/2021 O3 (PanSTARRS) reaches perihelion around 20-21 April, and assuming it will survive its closest approach to the Sun, we may see the 6th magnitude comet with the naked eye under dark skies, or with binoculars, from late April to May in the evening sky.

For more on observing comets, read our guide What comets and asteroids are in the sky tonight?

5 astronomical sights to observe in 2022

Our Solar System’s array of planets and moons provides us with a diversity of astronomical displays throughout 2022 thanks to each planet’s distinct orbit around the Sun and their changing proximities to Earth.

When it comes to visual observing and astrophotography, our view of the planets changes from year to year, much more so than with deep-sky objects.

The next 12 months hold much promise for UK astronomers, with some unique planetary events and much more to look out for besides.

Whether you’re new to visual astronomy, an avid astrophotographer or a seasoned observer, there will be something for anyone with an interest in the night sky.

Read on to find out how to prepare for a year of conjunctions, oppositions – and an increasing chance of aurora too.

Here are 5 night-sky events to look forward to this year.

1

Aurora in UK skies

When: First quarter of 2022

Equipment to use: Can be seen with the naked eye, but a DSLR camera and wide-angle lens is recommend

The Aurora Borealis is best viewed from polar locations such as Greenland and Northern Scandinavia.

This is because Earth’s magnetic field draws electrons from solar winds towards the poles to form the Auroral Oval at high northern latitudes.

Occasionally, it can be seen from northern parts of the UK.

But, due to the increasing solar activity, we may see the aurora creeping further south this year.

Indeed, 2021 finished on a high for aurora hunters in the UK, as a substantial X1-class solar flare in October allowed astronomers in Norfolk and Wales to catch a glimpse.

Auroral activity usually peaks around the spring equinox, plus we’re seeing further activity due to the Sun’s current position in the solar cycle.

Why is this? Well, the aurora is driven by the Sun; the more ‘active’ it is in terms of sunspots and solar flares, the greater the likelihood of a visible display.

This is because sunspots eject the solar energy that causes aurora; the more sunspots observed, the more intense the flare activity.

The Sun goes through ‘cycles’ of activity, each one lasting about 11 years, during which we experience peaks and troughs; the last peak occurred in 2014.

The current cycle, Solar Cycle 25, began in December 2019 and is expected to peak in 2025.

How to see the aurora

Observing the aurora is both a matter of timing and luck; a solar flare needs to hit at the right time and intensity for us to see it.

Events are difficult to predict beyond a few hours, so check monitoring websites at the earliest mention of solar activity.

Key ones to follow include AuroraWatch UK on Facebook and Aurora Service.

To stand the best chance of seeing a display, head for a location with a clear northern horizon.

It should be as free from light pollution as possible, because the aurora is usually quite faint in the UK.

Coastlines can provide a good clear northern view and remember, displays will be closer to the horizon the further south you are.

The aurora ‘in real-life’ looks different to how they’re portrayed in images.

From Britain, displays don’t appear as vibrant dancing ribbons.

Instead, they appear as spikes or pillars, and will be a subdued green colour. Really strong displays will show red elements higher up.

You can pick up further details by imaging the aurora. Any camera (or smartphone) that has a ‘manual’ mode can be used, so that you can alter the light sensitivity and exposure settings.

Because aurora displays move, limit long exposure times to avoid fuzzy images – 10 seconds is a good start.

2

Conjunction of the Moon and Jupiter

When: 19 July 2022

Equipment to use: Binoculars for the conjunction; a high-powered telescope to see the three planets; a DSLR camera to get creative.

Conjunctions provide a unique opportunity to observe planets near another celestial body, be that the Moon or another planet.

In July 2022 we’ll see Jupiter get 2°13’ to a waning gibbous Moon (60% illuminated).

Look up at the night sky to the southeast on 19 July and the two bodies will be the equivalent of a couple of little finger-widths apart.

Their proximity is best appreciated by eye or with a pair of binoculars.

Even though Jupiter and the Moon will be passing close together visually, they are still too far apart to fit in the same field of view with a small telescope.

While the night sky won’t be fully dark, both objects are easy to spot.

At about 3am, you should be able to catch Jupiter and the Moon close together, with Saturn and Mars also up.

Even better, the Milky Way will be directly overhead, with the core lying to the southwest.

The straight-ish line the planets form will provide an opportunity for some wide-field astrophotography too.

By eye, Saturn and Mars glow a soft reddish orange, making it easy for amateur astronomers to locate them.

How to see the conjunction

Head to a location with clear horizons to the southeast on 19 July.

The Moon and Jupiter will appear in the same field of view in a pair of low-power binoculars; however, due to the planetary activity it would be a good idea to bring a wide-aperture telescope as well to get the best views from your observing session, when the gas giant is part-obscured behind the Moon’s limb.

If you’re planning on some wide-field astrophotography, any DSLR with a wide-field lens (14-35mm) will do the trick.

Longer focal length lenses can still be used – pan across the view to create a panorama and capture the planets either side of the conjunction.

You could also use the conjunction to try capturing a composite image.

Take some images of the Moon with shorter exposures, and combine them with slightly longer exposures for Saturn, Mars and the Milky Way to create a more complete picture of the event.

3

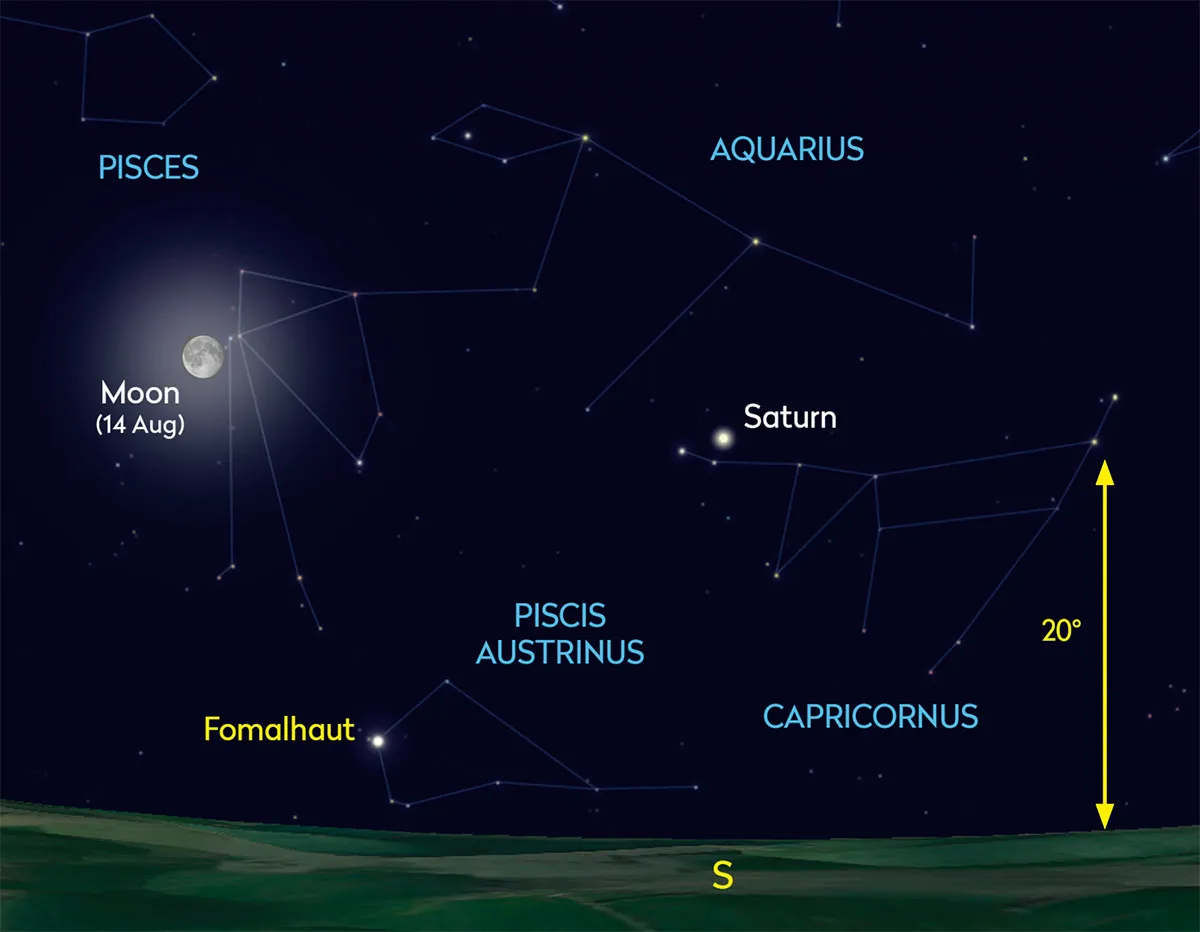

See Saturn at its brightest

When: 14 August 2022

Equipment to use: Identifiable by eye from its golden colour. Telescopes will bring out detail, anything from a small refractor (70–80mm diameter) to a long-focal length reflector. Use planetary cameras for imaging.

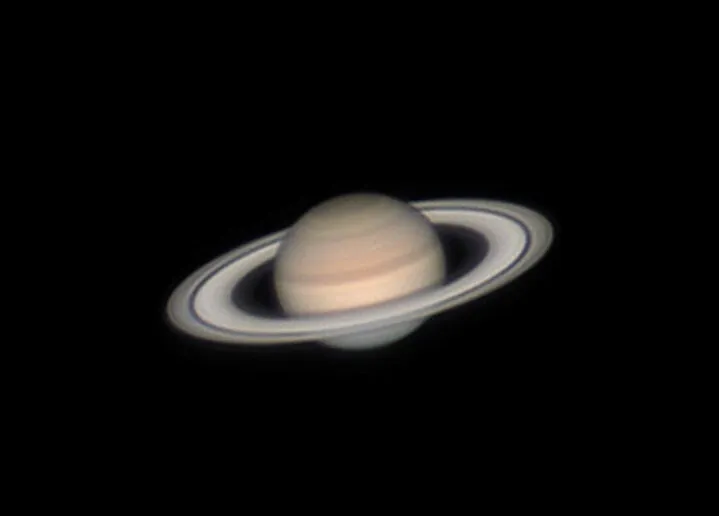

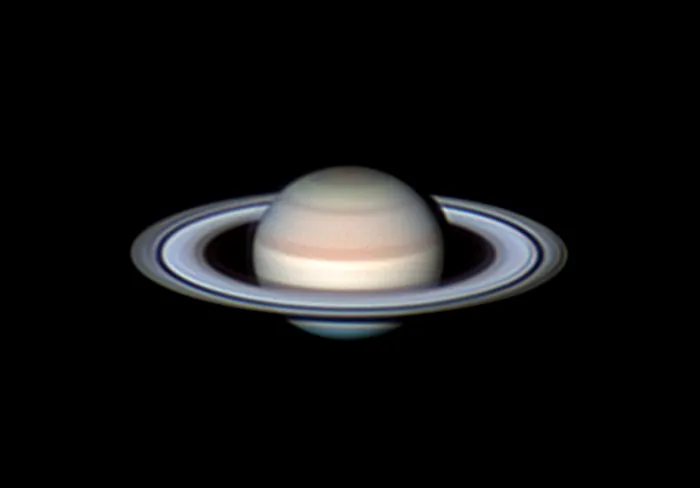

One of the most interesting planets to observe, Saturn reaches opposition in August, when it appears large and bright.

Opposition occurs when Earth lies directly between the Sun and a planet – indeed, the Moon is at opposition whenever it’s at full phase.

It’s because of this full illumination that it is so well presented.

Saturn reaches opposition roughly every year, and on this occasion it’ll be 8.86 AU (1.32 billion km) from Earth.

That’s 320 million km closer than the farthest it will be in 2022, 11 AU (1.64 billion km).

Saturn’s opposition will allow observers a clear view of its northern hemisphere and ring structure.

If atmospheric seeing allows and you have the equipment to achieve high magnifications, expect to see structure in Saturn's rings (such as the Cassini Division) and colouring or bands on the surface.

The great thing about Saturn, especially at times of opposition, is that even a smaller refractor in the region of 80mm will bring its rings and some level of detail into view with low-magnification eyepieces.

Binoculars won’t, however; they’ll allow you to appreciate the colour, but not the detail.

Because Saturn will be illuminated, its icy rings will brighten significantly – an occurance known as the Seeliger effect.

This is a phenomenon that can be appreciated by both imagers and observers.

How to see Saturn at opposition

Saturn will be visible all night on 14 August, starting at twilight in the southeast.

But it’s best viewed or imaged around midnight, when it culminates at an altitude of around 20˚ in the south.

Opposition gives astronomers the perfect opportunity to observe and image delicate details, however Saturn is heavily influenced by atmospheric conditions.

If the seeing is poor, use lower magnification eyepieces to avoid unwanted distortion.

We recommend starting with a 25–30mm eyepiece to locate it, and then stepping up eyepiece magnification until you struggle to focus or obtain a clean image.

Smaller refractors will allow you to see the rings and some level of detail at opposition using medium- to high-powered eyepieces.

Some of Saturn’s brighter moons should also be visible, including Enceladus.

Binoculars will resolve the shape, however the rings will not be discernible from Saturn’s disc, and could appear as ‘ears’ instead.

If you live in a light-polluted area, don’t worry. Planets are bright and still give a pleasing view, although you will lose a nice dark background for contrast, and views of the moons.

For help with this, read our guide to stargazing from a city and doing astrophotography from a city.

4

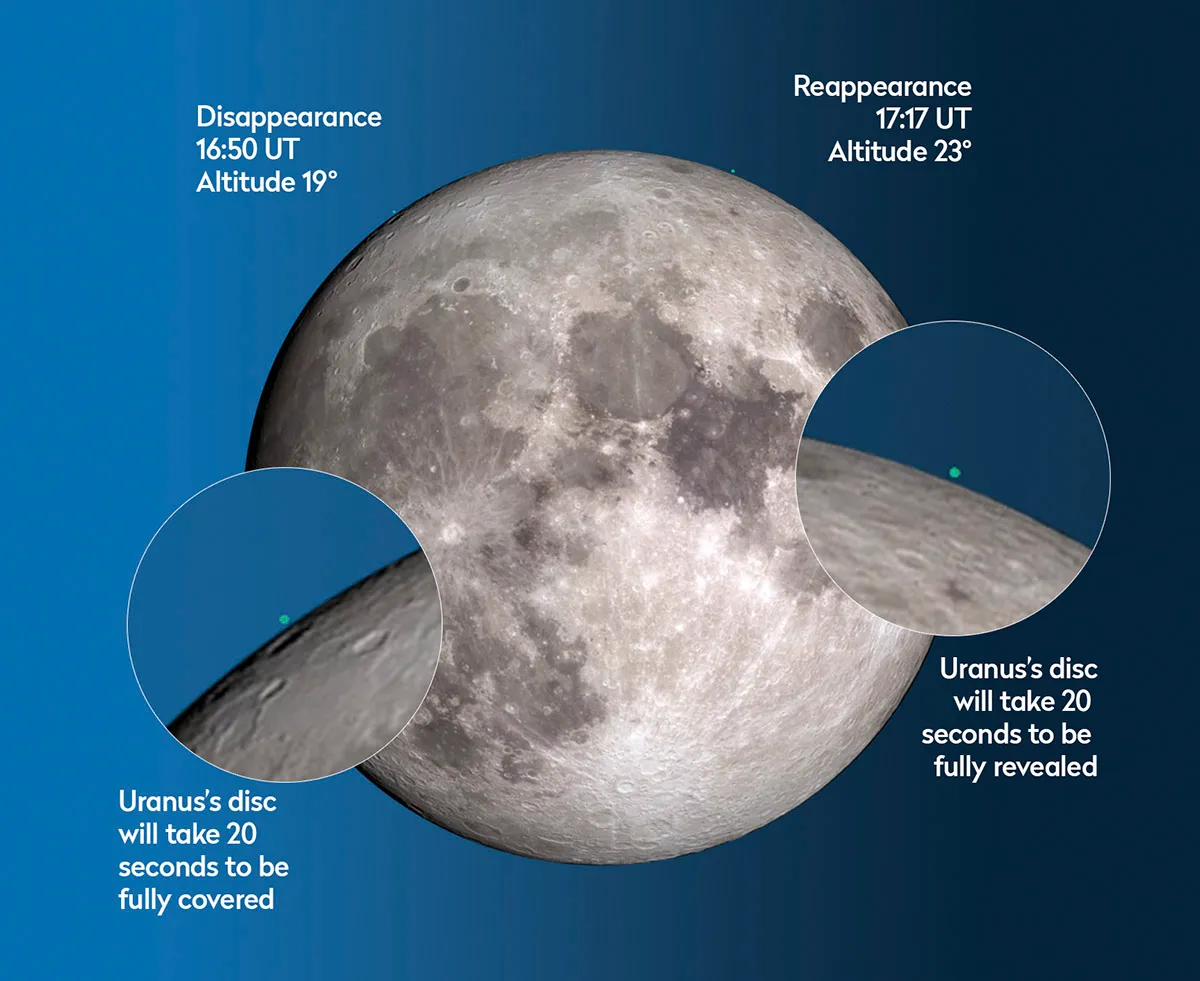

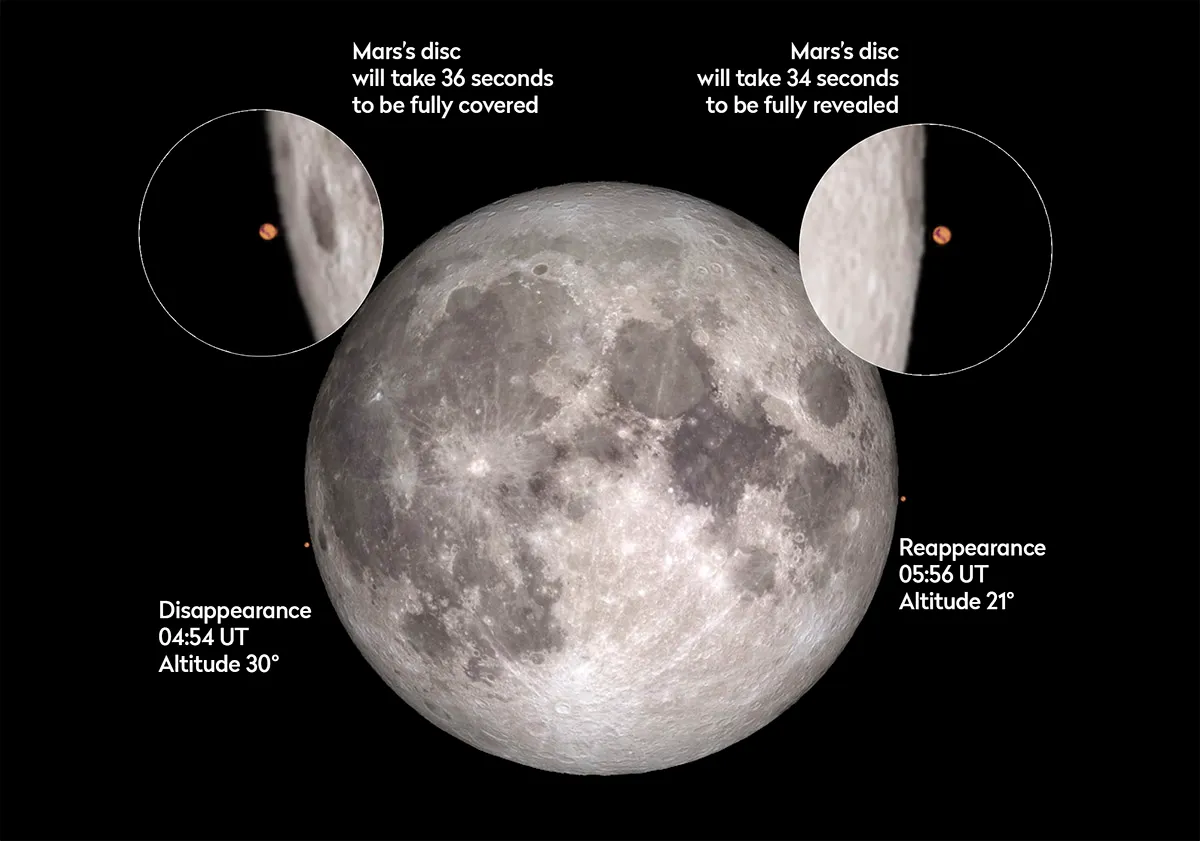

Occultations of Uranus and Mars

When: Uranus – 5 December 2022 and Mars – 8 December 2022

Equipment to use: For Uranus, long focal-length telescopes with large apertures (200mm+) are needed to ensure it appears larger than a speck. Use high frame-rate planetary cameras for imaging.

For Mars, a reflecting telescope (125mm+) will show details before the Moon washes out too much detail. Consider moving to a lower magnification telescope and eyepiece for the occultation.

December 2022 welcomes two lunar occultations within a few days of each other, when two different planets pass behind the Moon, ‘disappearing’ on one side before ‘reappearing’ on the other.

Because of parallax, occultations are location dependent; one place may see it, while others won’t because their view of the event can put the two objects further apart.

First, watch as Uranus disappears behind the Moon due east, in the constellation of Aries, the Water-Bearer.

Catch it about an hour after sunset. While not fully dark, UK astronomers should be able to see it.

See the Uranus occultation

To find Uranus as it occults, pop an RA of 02h52m40s and a dec. of 16˚08’N into your Go-To.

If you are looking at the Moon as a clock face, Uranus will disappear at the 10 o’clock position, at 16:46 UT.

It then reappears at 17:23 UT in the 1 o’clock position.

Expect Uranus to appear as a tiny blue-green disc; it’s challenging not only due to its distance, it’s also not as illuminated by the Sun as the inner planets.

A 94% illuminated Moon may disrupt views as the planet gets closer.

Imagers can vary short exposures to capture both bodies, boosting ISO or gain to increase signal from Uranus.

Don’t expect to capture surface detail without infrared filters.

See the Mars occultation

Mars‘s lunar occultation follows early on 8 December, when the Moon is at full illumination.

Mars will also be at opposition, at 0.54 AU (81 million km) from Earth.

The relative distance between Mars and Earth won’t be as small as this again until May 2031, making December 2022 one of the standout occasions to view Mars through a telescope in many years.

UK observers can see both the disappearance and reappearance of Mars, meaning a good opportunity for imagers to capture a composite sequence.

Set your alarm for about 04:30 UT and look to the west, where the Moon will be at an altitude of 29˚ between Taurus, the Bull and Auriga, the Charioteer.

Mars disappears at 04:55 UT and reappears at 05:56 UT while the Moon is still 20˚ above the horizon.

Because Mars is also at opposition, observers and planetary imagers might want to make a night of it and view Mars from 20:00 UT on 7 December.

Find a clear western horizon to capture the full occultation early the following morning.

Mars disappears at the 10 o’clock position and reappears at about 4 o’clock.

This guide originally appeared in the January and February 2022 issues of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.