Perhaps the best-known annual meteor shower of them all is the Perseid meteor shower, and in this guide we'll reveal our top tips for observing a Perseid.

The Perseid Meteor Shower gets its name from its radiant (the point in the sky where the meteors appear to come from) being in the constellation of Perseus.

Find out when the next meteor shower is happening and how to photograph the Perseid Meteor Shower

As one of the most prolific meteor showers, the Perseids feature in folklore and myth.

It used to be said that the Perseid meteors were the ‘tears of Saint Lawrence’, as some believed they were the sparks from the fire on which Saint Lawrence was martyred in 258 AD.

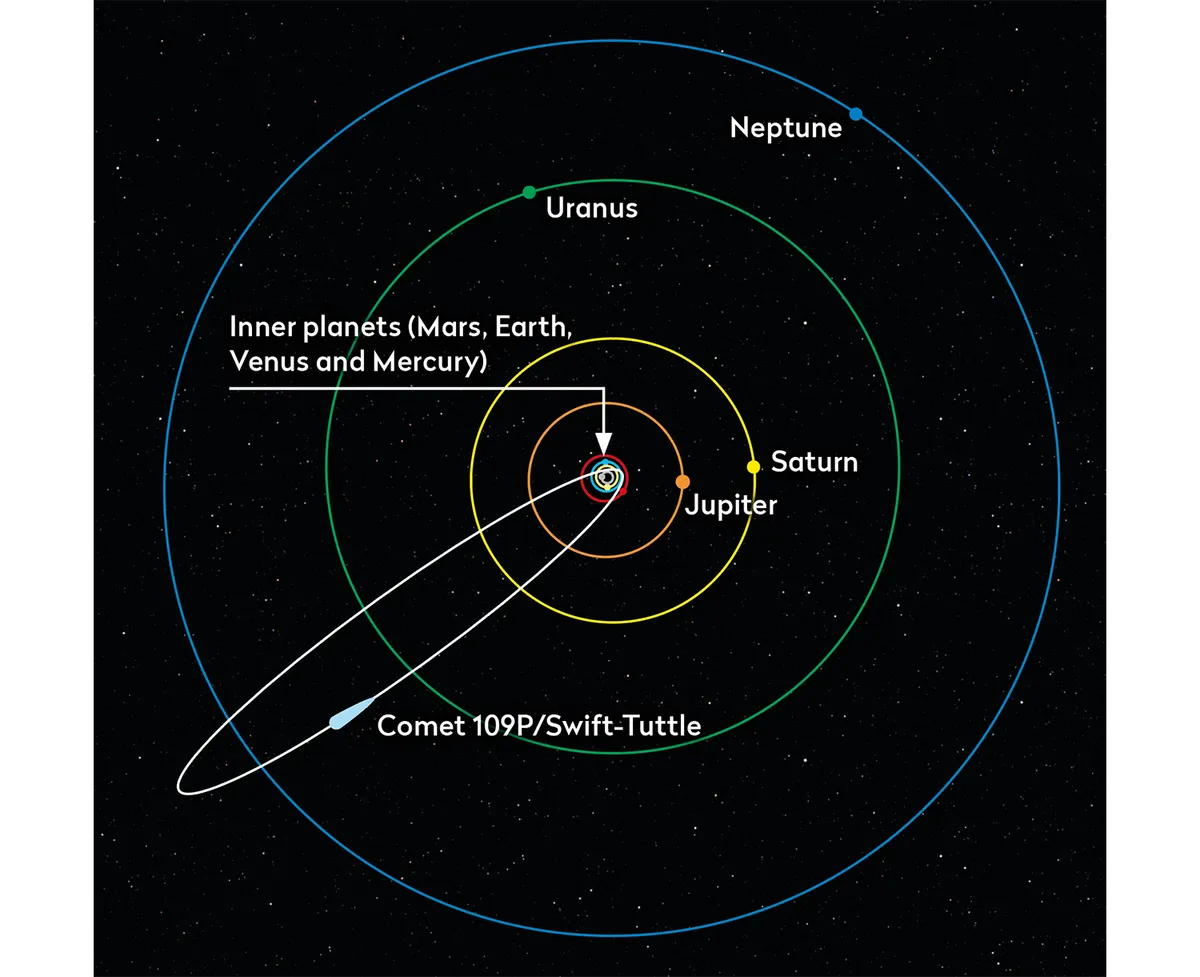

We had to wait until 1866 for the real cause of the shower to be identified: that was when Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli correctly identified comet 109P/Swift–Tuttle as its source, which passes through the inner Solar System every 133 years.

The Perseid Meteor Shower really starts on 17 July, when Earth first meets the outer edge of the debris stream from comet 109P/Swift–Tuttle, and runs until 24 August.

Here are some of the best ways to enjoy, understand and observe the Perseid Meteor Shower.

Learn the science of meteor showers

Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle’s elliptical orbit takes it out beyond Neptune. Credit: BBC Sky at Night Magazine.

Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle’s elliptical orbit takes it out beyond Neptune. Credit: BBC Sky at Night Magazine.

It is the dust in a comet’s tail that becomes meteors.

As a comet approaches the Sun, the increasing heat causes volatile material on the comet’s surface to evaporate, taking dust with it to create the tail of particles.

A comet’s tail can be quite spectacular to observe, and out in space the stream of dust can stretch much further, spanning the distances between planetary orbits.

For comets in short orbits, this process happens fairly frequently and, as a result, multiple debris streams from different comets are generated, the streams orbiting the Sun just as the planets do.

When Earth passes through one of these streams, the particles within it hit our atmosphere and burn up in it, becoming meteors.

In the case of the Perseids, most of these particles are the size of sand grains, but it is not uncommon for larger pieces to enter the atmosphere, creating fireballs.

The effect of a radiant is simply due to perspective; in much the same way as parallel railway tracks appear to meet on the horizon, so parallel meteor trajectories appear to come from one spot in the sky.

Find our more in our guide What causes a meteor shower?

A 2016 Perseid meteor over Cleveland National Forest, California, USA. Credit: Kevin Key / Slworking / Getty Images

A 2016 Perseid meteor over Cleveland National Forest, California, USA. Credit: Kevin Key / Slworking / Getty Images

Understand Zenithal Hourly Rate

The peak of meteor activity is when Earth meets the thickest part of the debris stream, with a predicted Zenith Hourly Rate (ZHR) of 80 meteors an hour for this year's Perseids.

It should be noted that the ZHR is an idealised figure – it’s the average number of meteors you would see in a very dark sky, with the radiant directly overhead, looking at the entire 180˚ of sky.

On the night in question, less than 80 meteors an hour may be seen – or there might be a great deal of activity where many more are seen.

This is why it’s worth observing!

Observing the Perseids requires no special equipment, but it is worth planning your session so that you get the most out of it, regardless of whether you plan to make observations or just watch the show.

Some basic materials will help with this (see below for more info). Make sure you are warm and comfortable; it can get surprisingly chilly in the early hours of the morning in August.

A Perseid meteor seen in the night sky above Corfe Castle, Dorset, United Kingdom, 12 August 2016. Credit: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images.

A Perseid meteor seen in the night sky above Corfe Castle, Dorset, United Kingdom, 12 August 2016. Credit: Dan Kitwood/Getty Images.

Observe the Perseids at the best time

It will be best to start observing the Perseid Meteor Shower at about midnight BST on 13 August (23:00 UT on 12 August).

The sky should be sufficiently dark by this time and the constellation of Perseus should be visible low in the northeastern sky.

The radiant of the Perseids is just above the main stars of Perseus; this is the area you should watch.

Close to the radiant meteors will be very short, but further away meteors will be longer.

It’s also useful to bear in mind that not every meteor you see will be a Perseid, so take care when identifying if what you have observed is a Perseid or not. To be sure, look at the direction the meteor took.

A genuine Perseid will be travelling away from the radiant, not towards it.

The length of its trail is also important; any longer meteors observed well away from the radiant should be checked by holding a straight edge, like a stick or a ruler, up to the sky to see if the trail points back towards Perseus.

Be prepared

A sun lounger and a red light torch are a meteor observer's best friends.

A sun lounger and a red light torch are a meteor observer's best friends.

Meteor observing doesn’t require any specialist equipment, but there are a few things that will make your session far more comfortable.

You can of course watch the shower in an ordinary chair, but a reclining outdoor chair or a sun lounger is very helpful.

You’re going to be looking up at the sky for long periods, particularly later in the night when Perseus is high in the sky, and a reclining chair will prevent neck strains.

You will also need a clipboard and a copy of the BAA meteor reporting form (see below). Other useful items include a red light torch and some pencils or pens.

Don’t forget to bring warm clothing or a blanket. It can get a bit chilly and damp in the early hours. A hot drink, some water and a snack to provide energy is also helpful.

Another thing that can be helpful is a tablet or smartphone with a planetarium app.

There are a number of free examples available, such as Stellarium. You will find this is very useful when working out your limiting stellar magnitude – just open up the planetarium and look up the magnitude of the faintest star you can see with the unaided eye.

Most planetarium software has a night mode, which will change the display to red, and don’t forget to turn your screen brightness down low.

Bright light, especially white light, will destroy your night vision and it can take up to 20 minutes to restore it.

It’s also possible to make your tablet and smartphone screen red. Try experimenting with your phone or tablet before going out to observe.

Credit: Pete Lawrence

Credit: Pete Lawrence

Look out for meteor trails and trains

As the constellation of Perseus rises higher in the sky, so the number of meteors you'll see during the Perseid Meteor Shower should slowly increase.

There will be faint meteors, but the Perseids generally produce quite a few bright meteors and fireballs.

As a meteor passes through the atmosphere, it heats up the air and creates a trail behind the meteor.

For larger meteors, there can be a longer afterglow along the trail and this is called the train of the meteor.

The Perseids are well known for producing bright meteors with persistent trains, the afterglow lasting some five seconds or longer.

Occasionally I have seen really brilliant Perseids that leave a smoke train behind them.

Record what you see

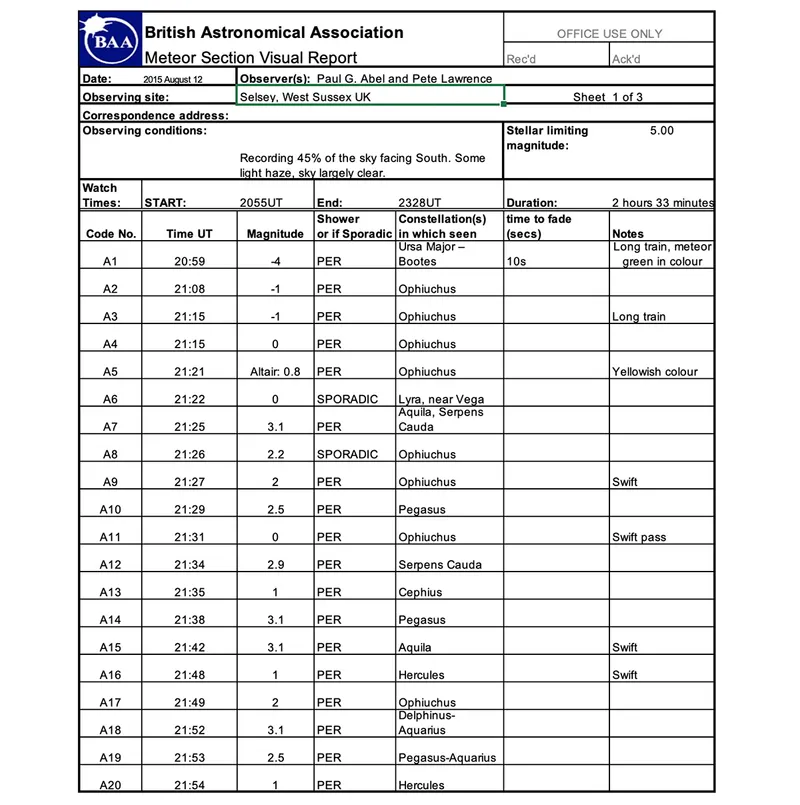

A completed BAA meteor form

A completed BAA meteor form

Meteor showers are great to observe with friends and family for fun, their unexpected nature adding to the excitement.

You can also make your meteor watch into scientifically useful data by systematically recording your observations.

By studying observations of a shower, astronomers can determine if there have been any changes to the radiant, and see how accurate the predictions for the time of maximum activity are.

All of this can be useful in determining any long-term changes to comet 109P/Swift–Tuttle, which produces the stream of particles that cause the Perseid Meteor Shower.

There are particular details a recorded observation needs to have and the British Astronomical Association’s meteor section has a visual reporting form that includes all of these.

Download the meteor observing form (PDF).

Above is a completed example from a previous Perseid shower.

At the top, there is information about the observer’s location: name, address and observing site.

There’s also space to record the time you started your watch and the time it was completed (both in Universal Time: BST minus one hour), and the overall duration of your observing session.

Another important detail to record is the magnitude of the faintest star you can see with your unaided eye. This will give you the limiting stellar magnitude of your observing site.

The rest of the form is about the meteors you’ve seen.

Stargazers observe the Perseid meteor shower over the Saskatchewan Summer Star Party, Canada, 10 August 2018. Credit: VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Stargazers observe the Perseid meteor shower over the Saskatchewan Summer Star Party, Canada, 10 August 2018. Credit: VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

You can give each separate meteor you see a number (Code No.) and record the time you observed it, your estimate of its magnitude (see left) and the constellations it moved through.

There is also a column to record whether each meteor was a Perseid or a sporadic.

Finally, you can record how long it took to fade from the sky, along with any other notes about the meteor, such as whether it was a particular colour or had a long-lasting train.

Once you have completed your observations, you can send your report form to the BAA meteor section.

You don’t need to be a skilled astronomer to take part in a meteor watch. All that’s required are a few simple items and a clear night.

If your skies are cloudy on the peak night of the Perseid Meteor Shower, 12 August, try again on the 13th as you may still see quite a few meteors.

All the observing techniques and the methods used for recording your observations in this article can be applied to other showers too.

Your observations of these showers will provide valuable information about the different meteoroid streams generated by the parent comets out in the Solar System.

A sketch showing Perseid meteors and satellites by Deirdre Kelleghan, Bray, Co. Wicklow, Ireland.a

A sketch showing Perseid meteors and satellites by Deirdre Kelleghan, Bray, Co. Wicklow, Ireland.a

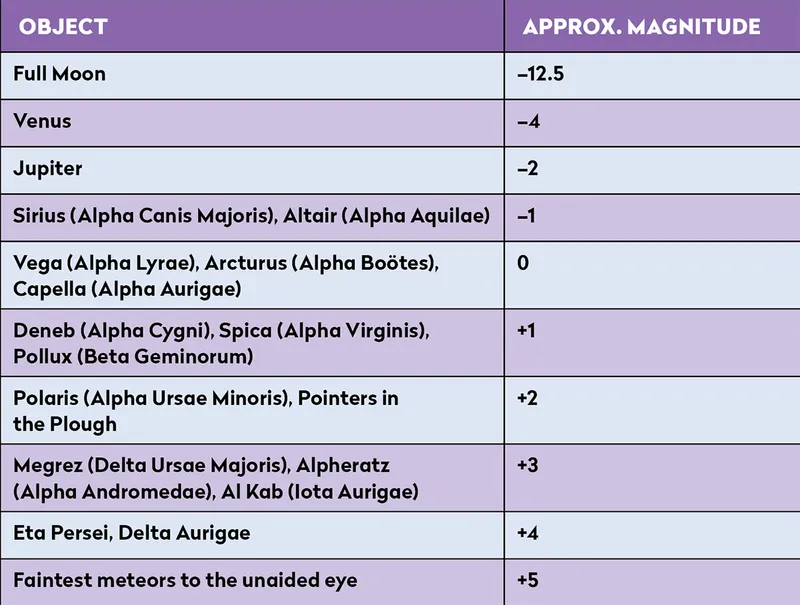

Estimate the brightness of meteors

Estimating meteor magnitudes seems straightforward on paper – just compare the meteor to a star of similar brightness – yet in practice it can be a little more challenging.

Why don't you try it this year for the Perseid Meteor Shower?

Meteors rarely hang around for long, so it will often be the memory of the sighting you are comparing!

Comparing meteors you observe to the stars in the table below will give you their approximate magnitude; you only need to estimate to the nearest whole magnitude.

Generally, the brighter the meteor, the larger the debris that is colliding with Earth’s atmosphere.

A list of different celestial objects and their magnitudes.

A list of different celestial objects and their magnitudes.

If you observe a brilliant fireball as bright as Jupiter, record its magnitude as –2. If a faint meteor about as bright as Polaris (the Pole Star) is seen, record its magnitude as +2, and so on.

Remember, the fainter an object is, the higher its magnitude will be.

Vega at magnitude 0 is brighter than Deneb at magnitude +1, and we can see all the way down to magnitude +6 without optical aid.

Under light pollution, though, we may only see down to magnitude +5.

For more on this, read our guide to stellar magnitude.

This guide originally appeared in the August 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.