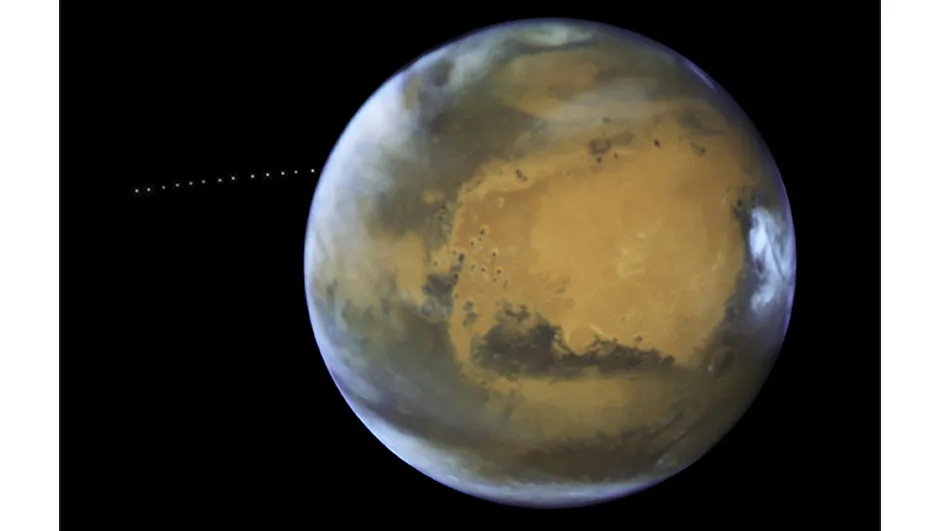

If we could permanently settle on other planets of the Solar System, what might our calendars look like? Credit: Scott Levine

Even though the guinea pig photo wall calendar near my desk says it’s still the middle of November, this weekend’s new Moon brings us to the start of a new month; a lunar month.

The month is an interesting way to measure time.

A day represents one rotation of an object. A year is one revolution, usually around a star; the Sun.

It’s convenient to talk about the length of days and years at other places compared to Earth’s: “Uranus’s year is 12 Earth years long”.

But those places have their own days and years that have nothing to do with Earth’s.

The month is rooted in human experience, tied to our view of the Moon. Venus? No one’s rushing to monthly status meetings there.

Astronomers use several different types of month.

A draconic month is the time the Moon takes to orbit from a node, one of the two points where its orbit crosses the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun (the ecliptic), and back.

A sidereal month is the length of one lunar orbit relative to the background stars.

An anomalistic month is the time from one perigee, the closest point in its orbit around Earth, to the next. All of these are around 27.5 days long.

A synodic month, or lunation, is the most similar all to our calendars of them all.

They’re about 29.5 days, and are the time between new Moons.

Any phase would work, though.

Since every calendar month except February is a little longer than a lunation, sometimes a calendar month can have two full Moons.

We call the second of those a blue Moon.

The next blue Moon will be on 28 January 2018.

Full Moons catch our eye but there are 'blue' phases every month.

This month, the Moon was an about-90 per cent-full waxing gibbous on 1 November.

We’ll have a blue 90 per cent-waxing-gibbous on 30 November.

The Moon that will rise next Halloween will be a blue third quarter.

The poetry writes itself.

Far away from home, there may be months, but not as we know them. Mars’s moon Phobos speeds around the planet in under eight Earth hours.

Years from now, people having picnics and throwing Frisbees under the stars in the Martian sky will see Phobos rise in the west, speed across the sky, and set in the east.

Then, a new month would start in the west again a few hours later.

There’d be a blue Phobos every Martian day (which, incidentally, is called a Sol)!

At the other end of the Solar System, the moon Neso takes over 26 Earth years to orbit Neptune once. That’s longer than it takes Saturn to orbit the Sun.

It’d be a long time between full Nesos, that’s for sure.

Which of Saturn’s moons would we use?

It might not seem like the most exciting word, but there’s more to a month than a page in a calendar.

Happy new lunation!

About the author

Scott Levine is a dad and astronomy lover who stares at the sky over his family’s home north of New York City. You can read more of his light-hearted look at astronomy at Scott’s Sky Watch.