There are a number of astronomical facts known to everyone. Venus is the brightest planet. Orion is the most obvious constellation in the winter sky.

The worst time to look at the Moon is when it is full. Right?

Actually, that's not true…

Find out when the next full Moon is visible and get weekly stargazing advice via our Star Diary podcast, YouTube channel and e-newsletter

Yes, when the Moon is full the light from the Sun blazing overhead wipes away all the rugged vertical relief from its rugged landscape of deep craters, towering mountains and meandering valleys, leaving only a flat, grey and white disc behind.

But when the eye socket craters are reduced to ghostly smoke rings and the deep valleys are sanded down to mere white dog hairs, other features emerge from the shadows to be revealed in all their glory: the long rays of shattered rock and fine dust that stretch away from its craters.

Hard to see when the Sun is low in the lunar sky and we see the Moon as a crescent or a gibbous disc, these suddenly shine like splashes of paint when the Moon is full in our sky.

The full Moon gets a lot of stick, and is often ignored or bemoaned by both lunar and deep-sky observers because of its brightness.

But it’s only when the Moon is full that we can truly appreciate the beauty of the magnificent rays that stretch across its surface.

We’re going to introduce new lunar observers to the fascinating bright lunar rays that are painted on the face of the Moon when it's full.

And hopefully help more seasoned observers develop a new (if grudging) appreciation for them too.

Lunar rays explained

What created the lunar rays? How did they form?

Imagine it’s the depths of winter and you’re standing on the banks of a frozen lake.

You pick up a heavy stone and throw it towards the centre of the lake, where it lands with a loud crack.

The ice is too thick to be smashed open by the stone, but the force of the impact sends chunks of icy debris spraying in all directions, which fall back to the ground as rays of bright snowy material.

Now scale that up a million-fold. Imagine you’re standing on the Moon, down near the south pole, 108 million years ago, watching a huge asteroid falling from the sky.

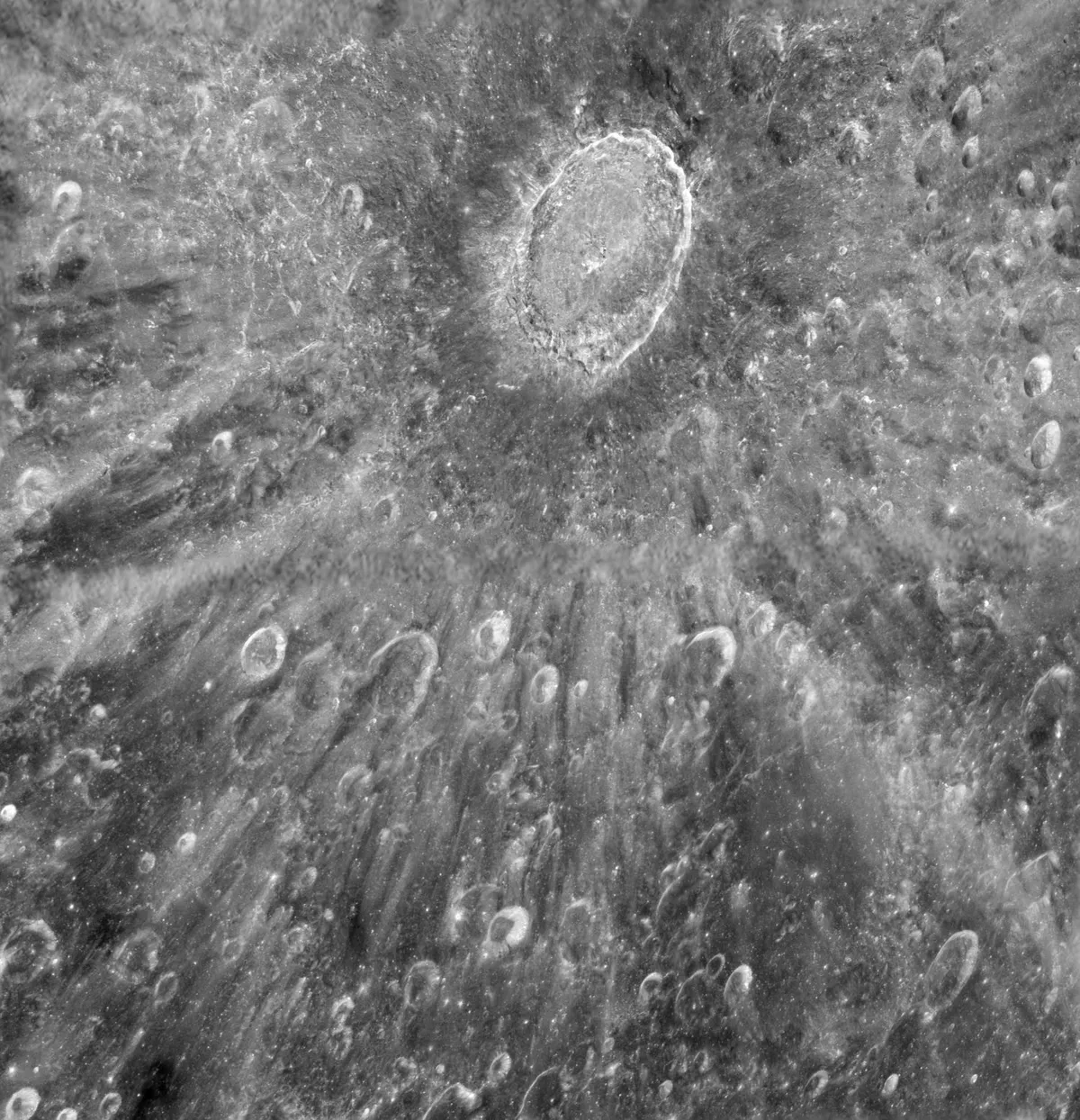

As the asteroid hits the Moon, there is an enormous explosion that sets the Moon ringing like a bell and blasts a crater out of its surface 85km wide and almost 5km deep.

It sprays vast amounts of pulverised rock and dust away from the impact site, arcing overhead, catching the sunlight, shimmering like diamond dust against the ink black sky before falling back down again in slow motion, like ashen fallout from a nuclear explosion.

Where it settles on the ground it leaves behind long rays of debris stretching back to the crater. That’s how lunar rays were formed.

Early lunar ray observations

Today we’re used to seeing high-resolution digital photos of the Moon showing its rays in glorious detail.

But they were observed and recorded long before the first grainy photos of the Moon were taken.

Hand-drawn maps of the Moon created centuries ago show them very clearly and very accurately, too.

In 1647, almost forty years after Galileo made his first famous sketches of the Moon showing craters along the terminator, the Polish astronomer Hevelius drew a map of the Moon as it appeared through his telescope.

Hevelius's map clearly shows rays splashed away from Tycho, Copernicus and Kepler, and even one of Tycho’s longest rays cutting across Mare Serenitatis.

A century later, German astronomer Tobias Mayer painted a beautiful colour chart of the Moon showing the sprays of its brightest rays.

You can see all these wonderful illustrations via Early Cartography of the Lunar Surface from the Library of Congress.

Observing lunar rays

How can you see these lunar rays for yourself when the Moon is full?

If you have good eyesight, you might be able to glimpse some rays with your naked eye at full Moon, especially when it's rising or setting and isn’t quite so blindingly bright.

But most people will need help from a pair of binoculars or a telescope.

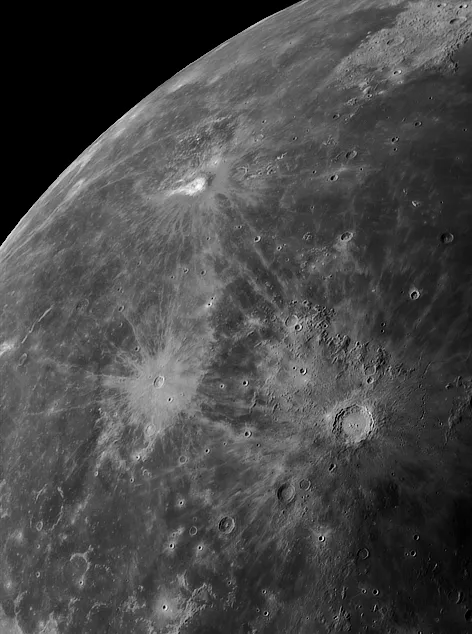

Through binoculars, the brightest, longest rays – from Tycho - stand out really clearly, in part because there’s so much contrast between them and the background sky.

Again, when the Moon is low in the sky and its glare is reduced because it’s dimmed by the atmosphere, the rays will be easier to see.

In fact, you’ll be able to trace the rays stretching away from Tycho almost all the way up to the top of the disc, and Copernicus’s rays can be followed up into the southern part of Mare Imbrium, beside the jagged spine of the Appennine Mountains.

But if you have a telescope, even a small one, your view of lunar rays will be spectacular.

Don’t be tempted to crank up the power. Low magnification is best, so you can see the whole of the Moon and see the rays crossing its features.

Seen through a telescope, the full Moon can be so eye-wateringly bright that you might also want to stop down your telescope a little by covering half the front of its tube, which will give you a much clearer, kinder view.

This may especially be the case if you've got some young astronomers keen to get their first glimpse through a telescope.

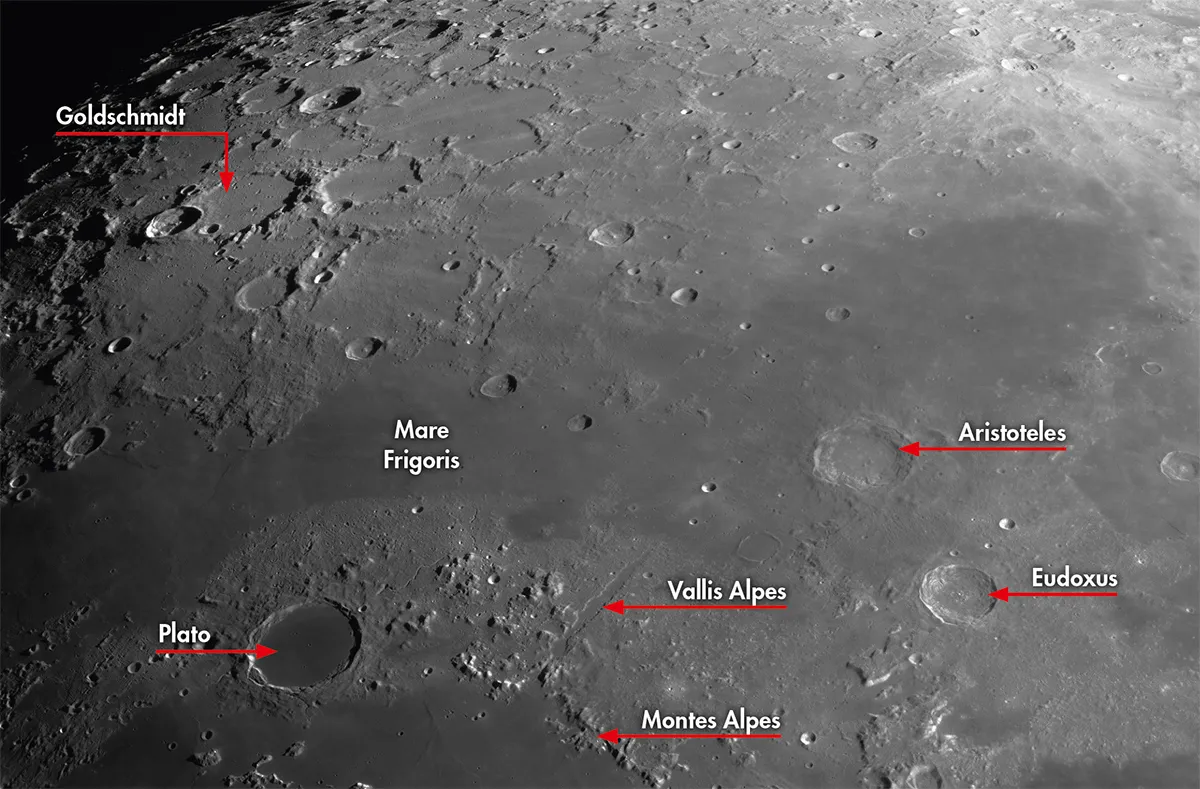

When seen through the eyepiece, Tycho’s longest rays can be traced for many hundreds of km across the Moon, stretching from the impact crater itself up to and across Mare Serenitatis and on into Mare Frigoris.

Copernicus’s network of rays is so bright and extensive seen through a telescope that it looks like white paint that has sploshed out of a tin dropped on the street.

7 beautiful rayed lunar craters

- Tycho

- Copernicus

- Kepler

- Aristarchus

- Proculus

- Byrgius A

- Messier A

Tycho

85km wide and 5km deep, southern highlands crater Tycho has the longest rays of any lunar crater, stretching up to 2,600km away from it.

Copernicus

Lying almost in the middle of Oceanus Procellarum, 93km wide Copernicus is at the centre of an elaborate, almost cobweb-like splash of rays.

Kepler

To the left of Copernicus as viewed through binoculars, Kepler is a small (32km wide), young crater surrounded by a roughly circular spray of bright rays

Aristarchus

Forming a neat triangle with Kepler and Copernicus, small crater Aristarchus has a very striking splash of bright impact debris on one side that looks stunning under higher magnifications.

Proculus

Blasted out of the shore of the ink blotch stain of Mare Tranquilitatis by a shuddering asteroid impact millions of years ago, this bright, 27km wide crater has a broad fan of bright rays spraying away from it that reach into neighbouring Mare Crisium.

Byrgius A

Located near the eastern limb of the full Moon, the ancient crater Brygius is pretty unremarkable, but when a more recent – in geological terms – impact blasted a smaller crater, A, out of its rim bright material sprayed away from it for hundreds of kilometres.

Messier A

Look at the eastern shore of Mare Fecunditatis when the Sun is illuminating it from overhead and you will see what looks like a grey-white comet tail on the dark lava field, stretching away from a pair of small craters.

These are Messier and Messier A, formed by the impact of an asteroid that most likely came in at a shallow angle and bounced, forming two craters, before coming to a halt. The narrow, bright rays shooting away from Messier A have been compared to a beam shining from a torch.

What are your favourite ray systems? Is there anything else observable when the Moon is full, or do you avoid it entirely? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com