When we read stories about astronauts training at NASA or living on the International Space Station, they feel more like fiction than real life.

What could an astronaut possibly teach us about solving our own problems?

Former NASA astronaut Mike Massimino reckons we can all learn quite a bit from the skills and experiences acquired by astronauts during training and while living in space.

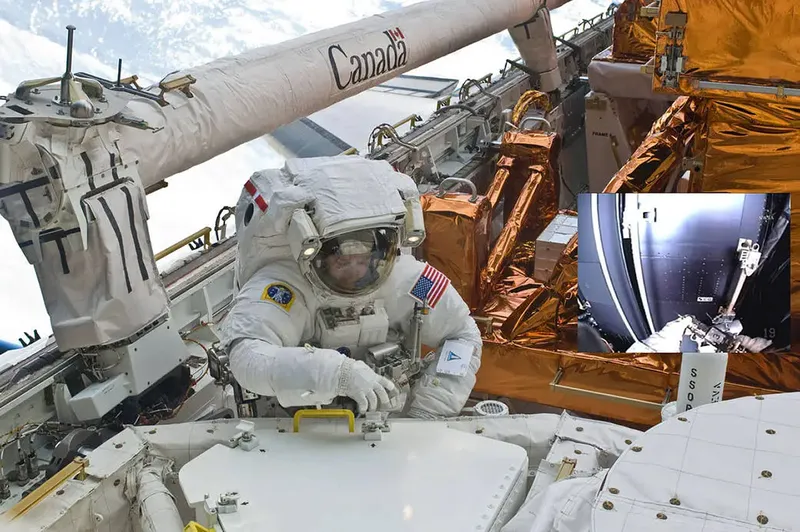

Massimino is perhaps best known for his work servicing the Hubble Space Telescope while in Earth orbit, and his latest book, Moonshot, features 10 life lessons that, he says, any of us can apply to our everyday lives.

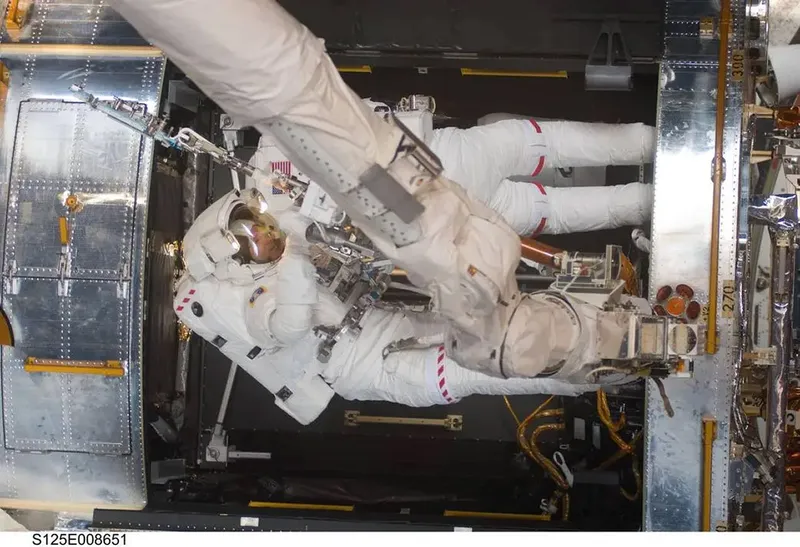

Mike Massimino joined NASA as an astronaut candidate in 1996, then flew on two Hubble servicing missions, first on Space Shuttle Columbia in 2002, then Atlantis in 2009.

We got the chance to speak to the astronaut, Hubble-fixer, space-walker and, now, Columbia University professor, about the lessons he learned as an astronaut, and his top tips for living a happy, successful life.

Buy Moonshot from Bookshop, WH Smith, Barnes & Noble, Waterstones

Video interview

What was your inspiration for writing the book?

I've done a great deal keynote speaking around the world about my experiences, and these are the stories that resonated most with audiences I've spoken to.

What people really are interested in is, how did we handle things like pursuing a dream personally, but also teamwork and leadership, dealing with change, and trust and the unknown, and making mistakes.

We know how to make mistakes! But what I found is the need to learn how to deal with them.

In the book are 10 things that I learned that are hopefully going to be helpful to people, not only in their professional life, but also in their personal life as well.

Each chapter title reads like a different guide for living…

Yeah, that's the idea, the book is called Moonshot, and it's a NASA astronaut's guide to achieving the impossible.

It’s a guidebook of the things I learned, mainly in my NASA career.

There are some bits about persistence and reaching a goal, and so on, which I learned before trying to get into the astronaut office.

But it’s mainly things I learned in my training and in orbit, and working in different places around NASA.

It was extraordinary. I learned from so many great people.

And some of of these things I may interpret a certain way, but basically it’s about the idea, the guideline, the rule, the takeaway and the stories behind them.

What mistake did I make that enabled me to learn this particular lesson, and then how did I apply that lesson?

Each chapter is pretty much independent of the other as well, so you can pick and choose.

Just about any one of the chapters is intended to be read independently if needed.

The book will remind readers of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff

The Right Stuff rekindled the dream that I had to become an astronaut.

In some ways it gave me the impression of astronauts as being really cool, with their camaraderie and so on, and that was something I was hoping to capture in my life.

I also talk about my interpretation of who astronauts were.

Sometimes if we're trying to do something with someone we look up to, we tend to put that person on a pedestal.

That's the way I was with astronauts when I was a little boy. They were superheroes and they were very cool guys, there's no doubt about it.

Shuttle astronauts were very cool men and women, and they were my heroes too.

But I once I got to know some of them by working with them at the Johnson Space Center before I was an astronaut, I felt like I fit in very well.

Sometimes you have this idea of what things are going to be like, but you really don't know.

Once you give yourself a chance to find out, you might surprise yourself that you fit in better than you thought.

You say in the book you initially weren't what you might expect a typical astronaut to be like

Yeah, I was this tall skinny kid when I was growing up, and I was afraid of heights, and I still don't like heights.

I'm not a thrill seeker, believe it or not, so I didn't think I would ever grow up to be like Neil Armstrong.

But once I started learning more about astronauts, I found out they were just regular people, especially the NASA folks.

A lot of test pilots are afraid of heights. I couldn't believe it.

I'm not the only person who doesn't like heights who became a pilot or an astronaut.

Sometimes we can psych ourselves out and think “I can't do that. I'm not talented enough. I'm not the right person.”

And you shouldn't limit yourself. You don't really know until you try. And that's one of the themes in the book.

Give it a shot. Give yourself a chance to realise what it is that you want to do, whatever that might be, whether it's doing something in a job or at home or at work.

Don't psych yourself out before you even try.

There can be an element of imposter syndrome sometimes, can’t there?

I think that's human nature. I think a lot of these things that make us feel like we're not ready, we're not worthy, we're not good enough, is because we're nice people.

Arrogant people who think they can do everything? Those are the ones you’ve got to watch out for.

I don't know if I could help those people! And those are not the kind of people we want to be astronauts.

Someone who's totally arrogant and thinks they know everything? That doesn’t work.

It's good to have confidence if you can, but I think a lot of people feel just because they're regular people that they need to work hard to try to fit in.

And I think that that's actually a good thing, and I think imposter syndrome probably is a normal thing for most people.

All of these things keep you humble, but they shouldn't prevent you from trying something you think is important, because then then you get regretful and that's not that's not a good place to be.

This is exemplified in the section where you describe how you had to pass a swim test but didn’t know how to swim!

Yeah! I was rejected to the astronaut class three times, including a medical disqualification that I was able to overturn.

On the fourth try, I was able to get through everything and pass, and was accepted.

NASA calls you on the phone and asks you: “Are you still interested in becoming an astronaut?”

Of course, you say yes.

I opened the information packet that came a few days later in the mail, and there was a paragraph about taking a swim test.

And at first I was kind of horrified, but then I was grateful they never asked me if I knew how to swim.

I think they just assumed that most people knew how to swim, you know, just like making a cup of tea, you know how to do certain things in life.

I wasn't a very good swimmer. I didn't like the water very much and never learned to swim well.

And now I was going to go through this test. I practiced as much as I could, but I wasn't feeling good about it.

My perception of astronauts was that hey were highly qualified people and smart and high achievers.

And here I am this pointy-head engineering professor coming into this cool test pilot community.

Hanging out with the ‘right stuff’ people, and I'm going to be flailing around in the water, really having trouble.

I thought maybe I could pass that swim test, but I was afraid that I might embarrass myself.

We had our first week of work, together as a class, and there were a lot of briefings in the classroom about standard stuff, and we had a visit from Neil Armstrong, which is anything but standard, in the same week.

But that first week was mainly administrative, getting used to what we were going to be doing.

We were preparing to begin the second week and Jeff Ashby, who was in the astronaut class before us, a Navy pilot and very experienced guy.

He came in to tell us “that's it for the week. But before you go home, I want to remind everyone that we have training on Monday and we're going to start with the swim test."

And I was thinking “how about a math quiz? Can we do something else? Does it have to be the swim test?”

He goes on to say “who are the strong swimmers in this class?”

And a few people raised their hand.

After that he goes “OK, who are the weak swimmers?”

And so I raised my hand that I was a weaker swimmer, or at least in my estimation, I was.

And he said "okay, everyone else who didn't raise their hand can go home, but the strong swimmers and the weak swimmers are going to stay after class.

And you're going to arrange a time to meet at a pool over the weekend, and the strong swimmers are going to help the weak swimmers with their swimming.

Because when we go to the pool on Monday, we don't want to leave that pool until everyone passes the test."

And so what I found was, if you're good at something, you could set a world record in the pool, for example, but if you left one of your classmates behind, you failed as well.

When you're good at something, your job is to try to help people who are struggling.

And the other thing is that you don't want to be the person holding back the class.

You want to be prepared and not let everybody down.

But also how important it was to admit that you needed help, because we were going into this as a team and we all wanted to pass.

Sometimes you might be struggling or there’s something going on in your personal life.

Sometimes you get hurt out in the field, and whatever it is that prevents you from doing what you're supposed to be doing, you need to speak up and get help.

It might be something beyond your control, or it might be that you don't understand what's happening because it's not something you generally understand.

And I think that's really hard for people, to admit that you need help with something. But if you don't, you're kind of holding back the team.

Part of the point is that when you can give help, you give it. But when you need help, you need to admit it.

And I think that can be harder.

It was really a fun opportunity to learn from some of my classmates. We really had a blast.

And it wasn’t like they were upset they had to help the weak people in the class. It was just part of the job.

We all went to that pool on that Monday and all were successful.

So that was my first lesson in teamwork and what mattered, and how the team’s success is really what's important.

So you can apply the lessons learned as an astronomy to more ordinary everyday situations?

Yeah, that's the story. No matter what it is, if your family's counting on you doing something and you're not able to, you should let them know

Or if you're at work, no matter what your job is and something's limiting or beyond you, you need to reach out and get help.

And look around at where you can be helpful, because what matters is that the team gets things done.

And we can think of the team at home with our families, or we can think of the team who we work with.

No matter what your job is, it doesn't matter. You're typically doing things as part of a greater team trying to get something accomplished and everyone is important.

And you need to help where you can, and get help when you need it.

What lessons did you learn being an active astronaut?

We used to say that you train like you fly, you fly like you train.

Whatever it is that you're doing, you're preparing for your job or preparing for whatever you're going to do.

You should train the way you can actually do it. And then when you do it, rely on your training.

Being in Earth orbit’s a bit different because now you're separated from people.

You have your crewmates around you, but you're off the planet, by definition. You’re a long way from home.

There's that connection that we have to our home, to Earth, to wherever we live, or where we work, or the community we're from.

You're not there right now. You're away, when you're in space.

And I think that happens to a lot of us now, working from home more since the pandemic.

We're away from people a lot. But we have to remember that people aren't really that far away.

Even in space, something I learned is that your control centre is always with you, even though you might not be in the same room with them.

So when we would do simulations in our training for our flights, Mission Control Center would practice with us.

We would only communicate over the communications line.

They put an artificial time delay in there, trying to make it seem like we were in space.

So when we got to space, that's the way we communicated with them, and even though I was a world away, I could rely on them.

And I had also had that job in the control centre, the Capcom talking to the crew, and I knew how important it was to keep that that line of communication going.

It's kind of like your life tether, you know, we're there for you.

I made a terrible mistake on the Hubble servicing mission. I stripped the screw trying to do a repair of an instrument.

I remember leaning out and looking at the planet, and we were over the Pacific Ocean.

I thought “I can't even get to a hardware store. I can't even imagine a hardware store that I can get to. I'm in trouble.”

But I had to tell them what had happened and they sprang into action and came up with a solution.

I didn't know what they were doing. I was just trying to keep myself moving forward and trying to be helpful.

In the book I talk about '30 seconds of regret'.

You make a mistake. Give yourself 30 seconds of remorse, beat yourself up internally and then move on.

And so I was doing that.

Another chapter in the book is You Can Always Make It Worse

I wasn't about to make anything worse and just tried to be a good active crew member.

They were working their job and they came up with a solution that was quite clever.

This handrail needed to be removed and I stripped the screw at the bottom of it, but it was loose at the top.

And the solution they came up with, after we had tried different tools and other things, was to just try to tear it off.

This handrail was a long handrail and I was able to just yank it off. And I didn't think of that.

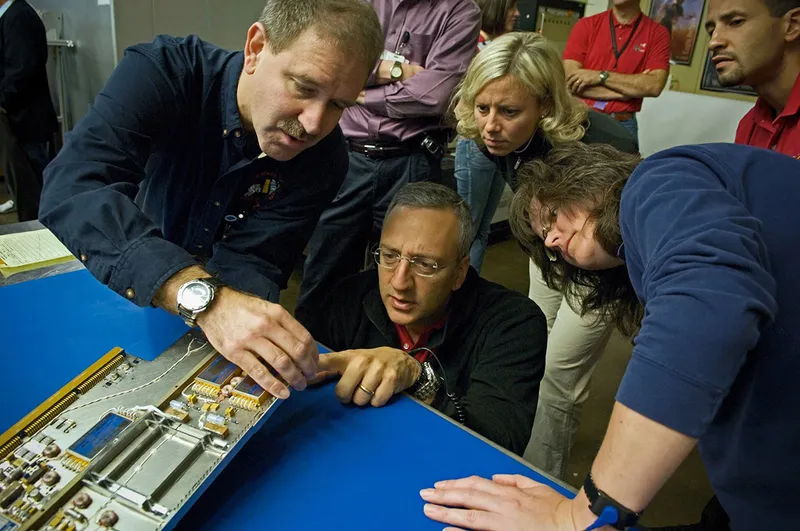

And no one in my crew thought of that, and no one in the front room of the control centre thought of that.

But it was a guy in the back room of the control centre, came up with this idea, what would he do if he was in his garage?

And he said “I would just tear it off”. Sometimes brute force is the way to go instead of all these fancy tools that we had.

And he called to the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and it was a Sunday afternoon, but they were at work of course, to support us.

I had no idea this was going on. They pulled an instrument out of the clean room, put it in the same configuration, and yanked on it with a fish scale, and it read 60 pounds of force.

And then they radioed that over and we gave it a try and it worked, I was able to tear it off.

But the whole message there is that even though you can't see your support system, you might be separated from them, they're still there.

Don't ever forget that your support system is intact, and that might be a family member or a friend or some sort of emotional support person, a doctor to help you when you need help psychologically or medically.

We should we should try to establish the support system. And once we do, don't forget that they're there for you, just like you would be there for them.

Reach out to your mission control centre. Don't feel like you're going through these struggles alone.

I really felt separated from the planet. I felt very alone when I did made this mistake.

But that team was still there for me. I'm up in orbit and they're down there communicating around the country to come up with this quick problem.

It took about an hour to an hour and a half to come up with that solution, but they did it.

I think whenever we're struggling, reach out to your mission control centre and be mission control for others.

Be that person other people can go to when they need help.

How did you deal with the physical and mental fatigue and the dream-like scenario of being in Earth orbit?

Being nervous about doing something I think is a good thing because it shows it matters.

If something's not important to you, you're not gonna be nervous about it.

But if you're nervous about it, it shows that you actually care, which I think is a good thing.

But there is a point where you have to actually execute that plan when the day comes, whatever that is, the presentation or the big event or whatever it is that you've been getting ready for.

Being scared isn't good because that can prevent us from doing what we need to do.

So what I found was, to try to get over being scared or nervous once the time comes is to trust your gear, that you have the right tools to help you, trust your training.

When you're given an assignment, your name isn't picked out of a hat. You're ready for it, even though you might not think so.

You wouldn’t be given that job if you weren’t capable. People aren’t setting you up for failure.

Trust that you're trained, that you're able to do whatever it is that you're being asked to do.

Trust your team. Life is typically an open book test. If you need help, you can go get it.

And then trust yourself. Say “OK I’m ready for this, I can do this and we're going to stick to the plan and execute as best we can.”

That helped me overcome the gruelling nature of spaceflight.

Let's execute our plan. If we need help, there’s going to be help available.

A chapter in the book is called Be Amazed.

For me, looking at the planet, it was so beautiful.

I felt like I was looking into an absolute paradise, that that nothing could be more beautiful than our planet.

I felt like I was looking into heaven, and that has stayed with me.

I'd love to go back and get another view of it, but what I find is that I don't necessarily need to go back to space to enjoy our planet, based on that experience.

And I try to share that with the reader, that we were looking at the planet from afar and admiring it, and it's absolutely beautiful.

I think that is the way that Earth was supposed to be viewed. You see its true beauty.

But when you get down to the planet, you can still see that same beauty.

Whether it's in nature, if you're out in a remote area and see mountains, but also just looking up at the sky and seeing clouds in a park.

If you live in a city with trees and squirrels running around or dogs being walked around Manhattan, where I live, or just the faces of the people on a subway.

It's amazing what we have down here in the buildings and everything we've accomplished, the museums.

Our planet is amazing, how it keeps us alive and it's fragile. We need to take care of it.

Every day we should try to be amazed just by what's around us.

Seeing the Earth from afar made me realise how beautiful it is, how amazing this place is.

I try to keep that in mind every day. Just how lucky we are to be here what a miracle it is that we are here.

It is difficult sometimes, isn't it? When you're annoyed that your bus is 10 minutes late!

Yeah! It's a lot tougher living on the planet than off of it. It's a lot easier in space.

You have problems. But you have a lot of people help you.

But yeah, daily life is not so easy.

I live in New York City. And if I've got to stand on the line and people aren't moving quickly, I do get aggravated.

But I try to I try to remember what it's like not to have those things too.

In space, we don't have a lot of crowds. We don't have weather and things we typically talk about on Earth.

I try to think about those times when I was in space and didn't have a cool breeze or the rain or these other miraculous things that we only have here on the planet, which includes crowds!

The other thing that hit me looking at Earth was my concept of where I'm from and how home changed when I was in space.

When I was a kid, I was from Long Island, Franklin Square was the name of the town.

And that was my whole world. Then as I grew up and started traveling a little bit more and going to college, I thought of myself as a New Yorker.

And then I thought of myself as an American when I was an astronaut, I was traveling around the world and flying in space with the American flag on my arm.

And I was an American. I worked for the United States government.

I'm an American and I'll always be all those things.

But now I kind of think of it a little bit differently when I think of home and where I'm from.

I think of Earth. That's where I'm from.

Looking at our planet, going around it so many times, what happened was this transformation.

That's home. Everything I know, everything I've ever known, every person we’ve ever known about, anybody alive today is in this one place.

And it's a home that all of us share, no matter where you're from, who you are, anywhere on the planet, all of us share that same home.

How do you feel about the future of spaceflight?

I think the astronaut program has changed a lot.

I look back on when I was a kid and they were working toward the Moon.

Even the flights that I don't remember, which were before the Apollo flights, the Mercury and Gemini flights.

It was about going to the Moon and it was considered this wonderful age in space exploration.

It is the greatest accomplishment ever, I think, landing people on the Moon.

Even though the American taxpayer was primarily involved, it really was seen as an accomplishment for the whole world.

It was a human accomplishment.

And then we moved on to Skylab and the Space Shuttle. And that was the focus.

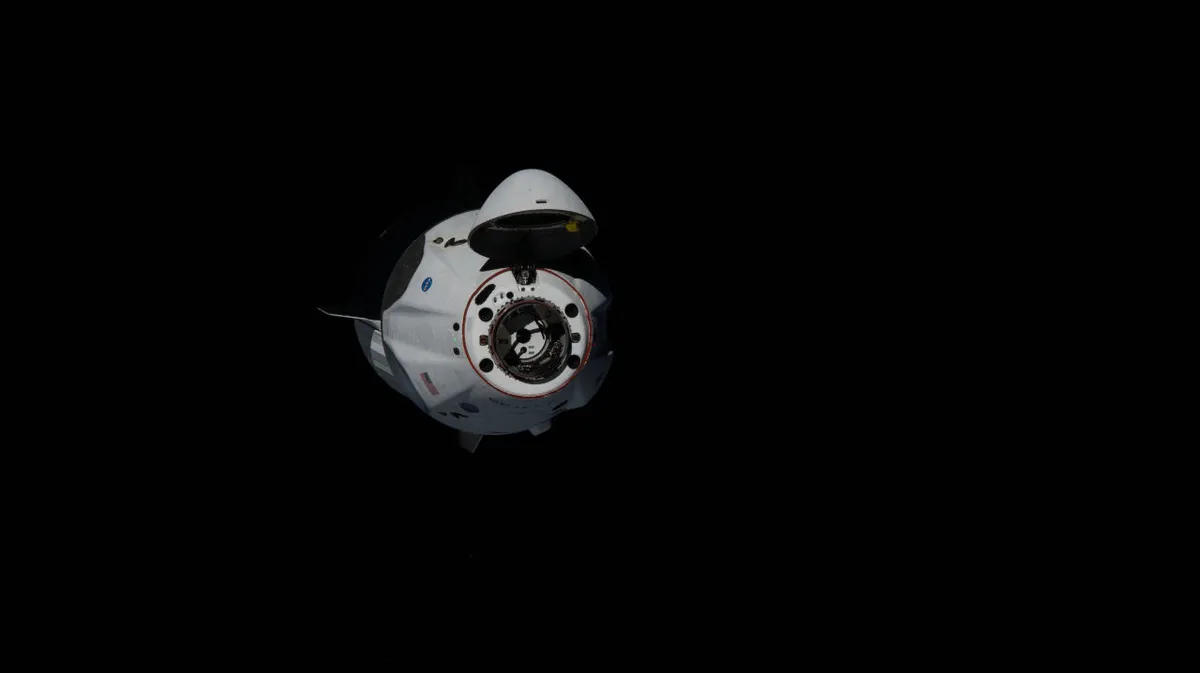

And now the focus is on space stations for astronauts and flying up on a SpaceX Dragon or on the Russian Soyuz.

And so it just changes and whatever happens, it's always moving forward.

And even though you get enamoured with something, it's not going to be there forever.

I think the major change that I've seen since the Shuttle program ended was the emergence of these private companies, and NASA had a lot to do with it.

NASA wanted the Space Shuttle to be a commercial vehicle, to eventually be flown by commercial airline pilots to take passengers different places.

NASA looked at the ending of the Shuttle program as an opportunity to involve more of the private companies and to help push the privatization of space.

The care of the spacecraft and the crew was going to be the responsibility of a private company. And we had never done that before.

And we were sceptical that that was going to be possible. They were going to be using a lot of new technology, including automation that would do a lot of the jobs that astronauts had done in the past.

So we were very sceptical, kind of worried about all of this and didn't like the idea at first.

But then we started building confidence when we saw what they were able to do, and confidence in the automation, because it seemed safer than what we had been accustomed to.

And it could reduce your training, so career astronauts don't need to worry as much or train as much to fly the vehicle.

They can concentrate on other things like doing spacewalks and experiments and working the robot arm.

99% of the stuff we trained for, for the Space Shuttle, it was all these failure procedures, modes that we never would encounter.

Now with automation taking care of a lot of this stuff, you cut down your training and you can concentrate on other things.

And it makes it easier for people to fly in space who aren't career astronauts. So more people can go.

And new technology like returning the vehicle so you can use it again, refuelling it and going again.

This reusability is bringing the cost down so that the access to space has increased dramatically.

My students at Columbia have been able to fly experiments in space. And this sort of thing would be unheard of even just a few years ago.

So when I look back that we were so worried about these changes coming and how it would end the space program, really what it did is allowed the space program to flourish, and we were really on the brink of greatness.

Now that these private companies are getting more established, and it's not just Space X and some of the others that we know about it, it's also a lot of smaller companies that are getting involved.

Students or young people looking to have exciting careers can look at the space program, not just working for a government or a big government contractor, but also working as an entrepreneur for maybe a smaller private company.

There's a plan to turn the Space Station over to a commercial company, and other companies are looking to build their own space stations as more and more people get access.

I think those changes that NASA made 12 years ago or so have led to that possibility.

And I think Mars is a place that's going to take a little bit longer to get to, but eventually we'll be sending people there as well.

Moonshot by Mike Massimino is a guide to success written by a former NASA astronaut and space-walker, and is published by Hachette.