A blob of gas found in the vicinity of the spiral galaxy M94 could be a starless, dark matter galaxy.

This blob is exciting astronomers because it could be the first example of a type of object long predicted by our leading cosmological theory:

A small galaxy with gas, dark matter… and no stars.

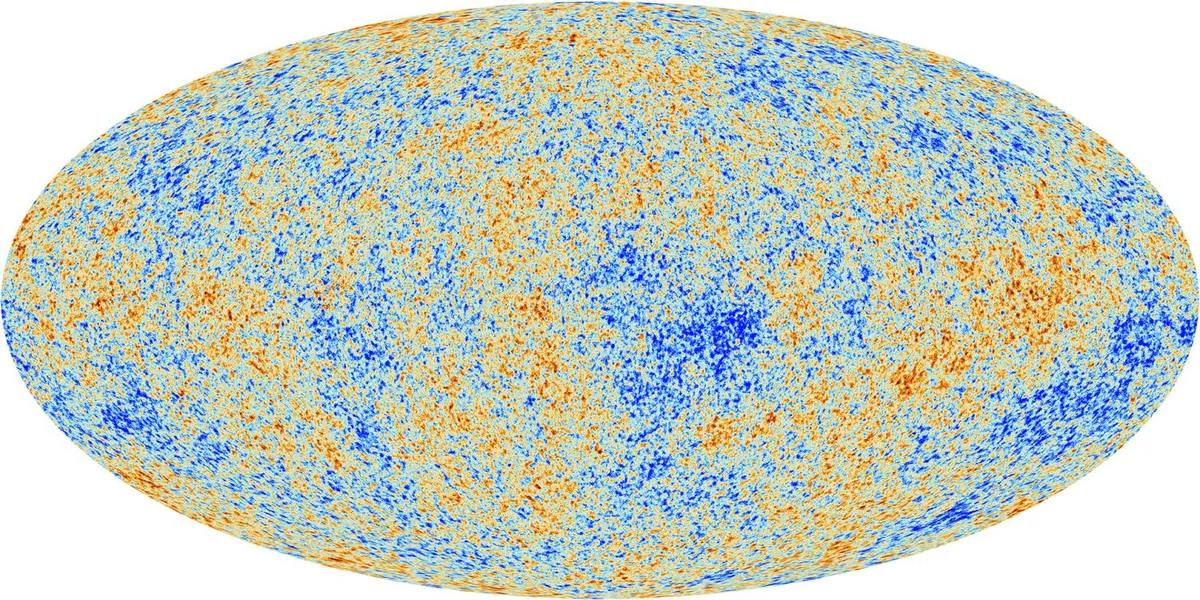

Our understanding of how gravity sculpts structure in the Universe says that from the tiny initial fluctuations in density that we see in the cosmic microwave background, objects of all masses will form.

But only in the largest – those with a mass above a critical limit, which changes over time – is gravity expected to be strong enough to reach the density required for star formation to happen.

As a result, scattered all over the Universe there should be smaller, failed systems that didn’t reach this limit.

These have been given the name of REionization-Limited-HI Clouds (RELHICs for short) by Alejandro Benítez-Llambay and Julio F Navarro, authors of a paper on the subject.

Has the first of these failed, starless galaxies been found?

Maybe.

How to find a starless, all-dark-matter galaxy

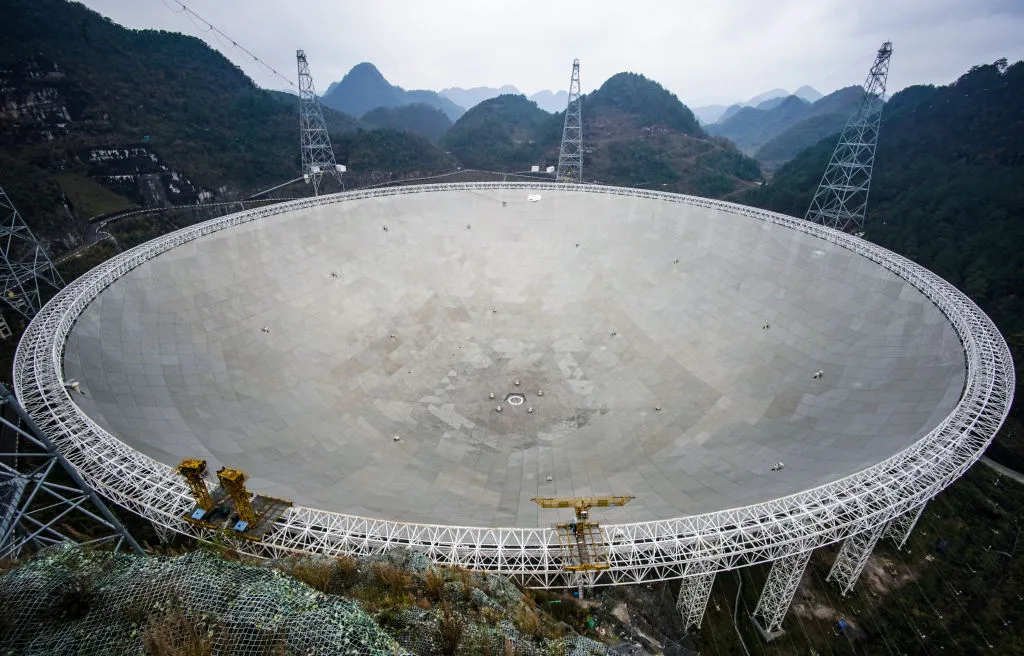

A team of Chinese astronomers used the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Radio Telescope (FAST) in southwest China.

Think of it as a larger and more modern version of the recently collapsed famous Arecibo dish in Puerto Rico.

During their observations, they detected radio waves at a wavelength of 21cm.

These are associated with hydrogen, coming from a point in the sky just slightly less than a degree from M94, in the constellation of Canes Venatici.

If the emission is indeed from hydrogen, it seems to be receding from us at about the same speed as the more massive galaxy, making it very likely to be part of the same cosmic group.

Lots of gas, but no stars

The discovery, called ‘Cloud-9’ by the team, could be a satellite galaxy of M94, but if so it’s a strange one.

The deepest imaging we have so far shows no signs of stellar light at a position corresponding to the radio source.

However, given the data in hand, a small luminous galaxy might still be lurking, hidden at the cloud’s centre.

The modelling in the paper suggests that, assuming no stars are found, it could have a mass 5 billion times that of the Sun.

This is small for a galaxy, though not unprecedented.

The material in it is slightly more spread out than predicted, a discrepancy Benítez-Llambay and Navarro explain by suggesting that these objects may have a different distribution of dark matter than a ‘normal’ galaxy of the same size does.

The galaxy may also be a bit more massive than otherwise expected.

What's next?

This is undoubtedly an exciting discovery, and I’m sure that telescopes will soon be swinging to observe Cloud-9.

Top of the authors’ wish list will be to get higher-resolution radio observations.

A single dish like FAST cannot match the performance of an array, and the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa has the capability to give us a much sharper view of how the gas is distributed.

And even that is just a precursor to the much larger Square Kilometer Array.

Long-exposure imaging could show gas in the cloud’s outskirts, and the Hubble Space Telescope would be ideal to look for any stars that exist.

Expect to hear more from Cloud-9 soon.

Chris Lintott was reading Is a Recently Discovered HI Cloud near M94 a Starless Dark Matter Halo? by Alejandro Benítez-Llambay and Julio F Navarro.

Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2309.03253

This article originally appeared in the November 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.