When I became fascinated by astronomy at the age of six (in 1929), professional astronomers paid little attention to the Moon, which was widely regarded as boring despite its undoubted beauty.

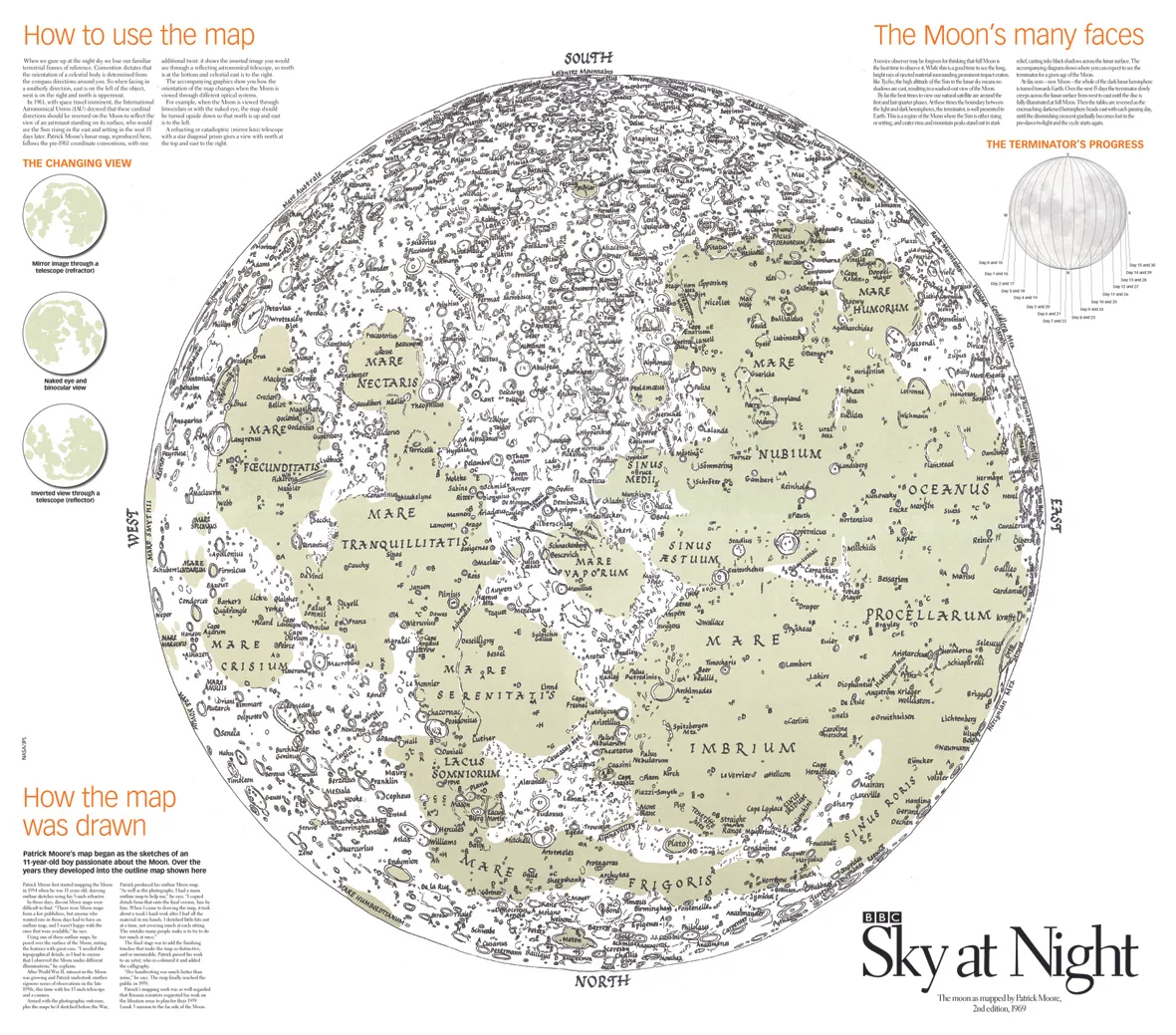

This meant that available maps were chiefly the work of amateurs.

I started keeping lunar notebooks in 1932 and soon realised that I would have to learn my own way around the Moon.

I decided on the best way to do this: I saved for a telescope and acquired a 3-inch refractor, which I still have. It cost me the princely sum of £7.10s.

Though there have been no major structural changes on the Moon for at least a thousand million years, its appearance alters very quickly, due mainly to the changing angle of the Sun’s rays.

Some people are surprised to learn that a crater is not in the least like a steep-sided well or mine shaft.

Drawn in profile, it is more like a shallow saucer (not a flying saucer, I hasten to add).

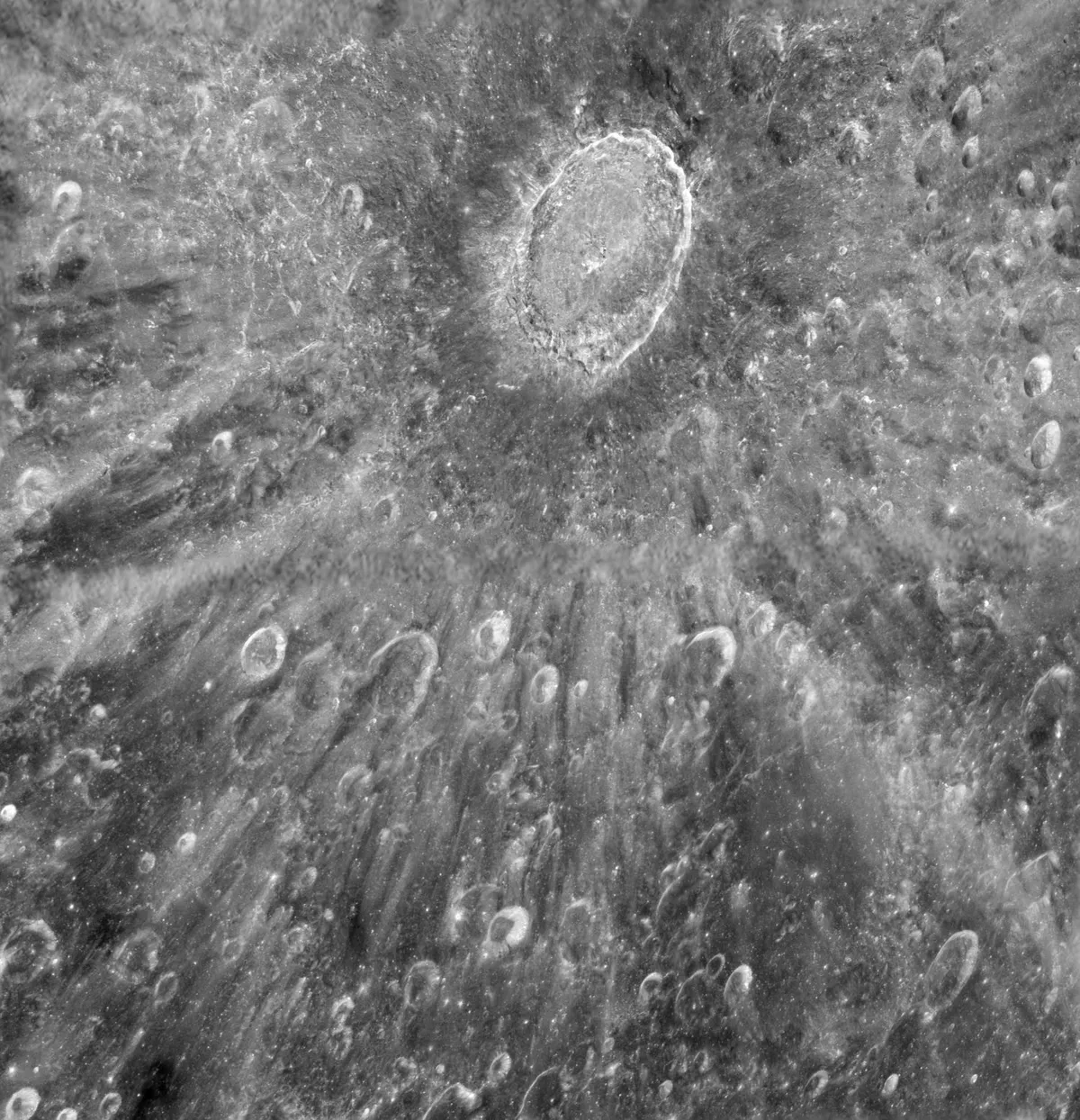

When a crater lies at or near the terminator – the boundary between the sunlit and dark hemispheres of the Moon – its floor is largely or completely in shadow and the effect is spectacular.

When the Sun rises over it, the shadows shrink and the crater may become very hard to identify.

Near full moon there are almost no shadows at all and the whole scene is dominated by the bright rays or streaks coming from craters such as Tycho (craters are named after prominent people of the past – Tycho Brahe was the last great observer of the pre-telescopic period).

Anxious to observe

My plan was to take what was just about the only outline lunar map then readily available and to make three drawings, at different times, of every named feature shown.

It was a year before I was satisfied – the clouds seemed to cover the sky whenever I was particularly anxious to observe, but at the end of the series of observations I was confident that I really did know the lunar surface.

What’s more, I had no trouble in identifying the craters, mountains, ridges and minor features such as the crack-like features known variously as rills, rilles or clefts.

The drawings themselves were of no scientific value whatsoever, but that was not my reason for making them: I was now ready to attempt something which might possibly be useful.

My faithful refractor was joined by a 12.5-inch reflector.I also had the occasional use of a 6-inch refractor.

I had learned how to avoid some elementary pitfalls of mapping.For example, I never try to draw too large an area at any one time, because inaccuracies are bound to creep in straight away.

The Russians asked me for my charts of the libration areas - I hope some were mildly useful to them - and the images came through when I was actually presenting The Sky at Night.

If I wanted to draw the 60-mile-wide (96km-wide) crater Plato I would make the crater at least an inch across.

Also, everyone has his own style of drawing and much of the result depends upon one’s artistic ability.

Illustrators such as David Hardy and the late Leslie Ball can make drawings which look completely realistic.

I, however, cannot, so I strive for accuracy, using pencil and, for shadows, Indian ink.

Between 1939 and 1945 my observing book was blank – I had other things on my mind! – but when I was able to return to observation I concentrated on the libration areas, which are carried in and out of view and are always foreshortened.

One could make interesting discoveries in those days.

In 1946, using my new 12.5-inch, I came across a large, complex crater right on the limb, which was not on the map.

I drew it and called it Crater X; it has now been named after Einstein.

Then, on 16 December 1948, while examining the terminator, I saw what I thought to be a small Mare.

I sketched it, and sent in a report to the lunar section of the British Astronomical Association, then directed by HP Wilkins.

He confirmed it and I suggested the name of the Mare Orientale or Eastern Sea, because it lay on what was then referred to as the eastern limb of the Moon.

What I did not know, and had no means of knowing, was that it is one of the most important of all lunar features – a huge ringed structure, almost all of which is permanently invisible from Earth.

I had been lucky enough to catch the tiny fragment which was available.

Years later, observers in the United States re-discovered it, but the name of the Mare Orientale was retained.

However the International Astronomical Union held a vote at a General Assembly, the idea being to follow the astronautical orientation and reverse east and west.

I was among those who opposed this proposition, but we were heavily defeated.

As a result, the Eastern Sea is now on the Moon’s western limb.

A great moment

During the 1950s it became clear that rockets to the Moon were imminent and, as a result, professionals began to give the Earth’s satellite their full and undivided attention again.

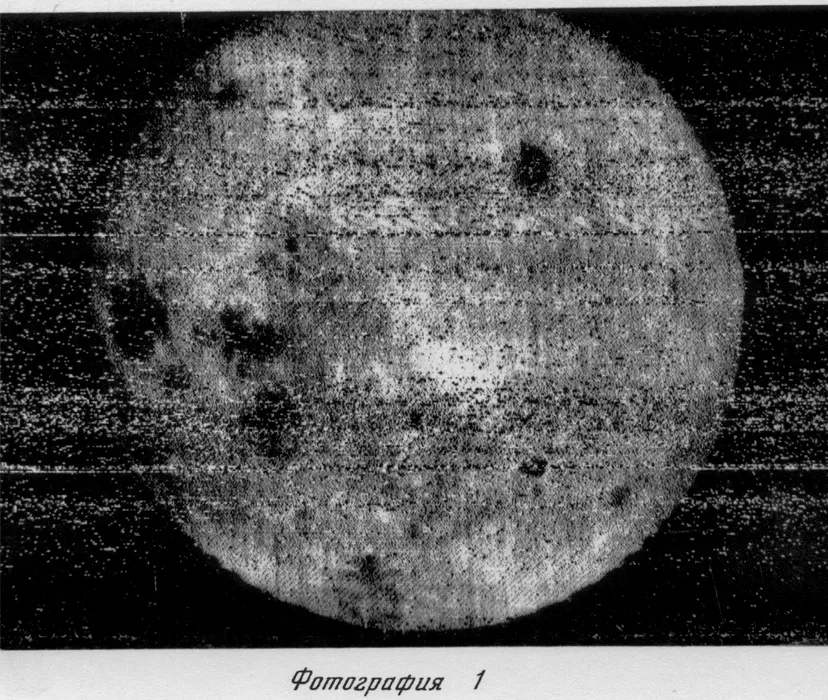

In 1959 the Russians sent their spacecraft Lunik 3 on a round trip and obtained the first views of the averted hemisphere which, predictably, turned out to be just as cratered and barren as the areas we have always known.

I well remember my excitement.

The Russians had asked me to send over all my charts of the libration areas – I hope some of the charts were mildly useful to them – and the images came through when I was actually presenting a live Sky at Night television programme.

It was a great moment.

Let me stress that I was a minor figure in a large team of observers and, compared with others, my contribution was infinitesimal.

Also, any work I did is now completely obsolete.

Today any well-equipped amateur, using modern electronic devices, can produce results completely beyond me, either then or now.

The amateur can still be a real help, but old-fashioned lunar sketching, with pencil and paper, is a thing of the past – except for giving the observer sheer pleasure.

One has to move with the times and I have to regard myself as something of an astronomical dinosaur.

All the same, I have an inward feeling of satisfaction when I see pictures of the Mare Orientale!

This feature was originally published in June 2005 in BBC Sky at Night Magazine. The late Sir Patrick Moore was one of Britain's most famous astronomers and the original presenter of The Sky at Night.