As the lighter nights begin to swing around in May, one thing I like to do is fire up Stellarium and plan out all the things I want to photograph when proper darkness returns in the late summer.

Almost always, the target that occupies me the most, no matter how many times I’ve imaged it, is the Milky Way.

Widefield, nightscape or long-focal-length close-up – it doesn’t matter what format we’re talking about, there’s always something our Galaxy can offer.

For more advice, read our beginner's guide to astrophotography or our guides on DSLR astrophotography and how to use a DSLR camera.

Sign up for our latest online astrophotography Masterclass

Find out more about the BBC Sky at Night Magazine DSLR Astro Imaging Masterclass.

It’s important to think ahead when it comes to Milky Way imaging.

The view changes from month to month, week to week and even hour to hour throughout the night.

And the best time to photograph our Galaxy from the UK, in my opinion, is the first weeks of August.

Not only has astronomical darkness come back for most of us in the UK by that point, but you also don’t have to wait all night for the band of the Milky Way to be positioned close to the meridian.

From a composition perspective I love how the core of the Galaxy and the swathe of its spiral arms, arcing up into the eastern sky, are positioned as midnight approaches.

If you've never tried to photograph the Milky Way, late summer is a great time to get started.

So read on as we introduce you to shooting the spectacular celestial metropolis that we all call home.

Kit to use for photographing the Milky Way

There are lots of ways to photograph the Milky Way with lots of different types and levels of equipment.

It’s one of those targets you can start off imaging as a beginner and keep coming back to as you get more experience, finding new and different ways of photographing it.

Recent advances in smartphone camera tech mean it’s possible to get widefield images of the Milky Way using high-end models equipped with low-light imaging modes.

For more on this topic, read our guide on how to photograph the night sky with a smartphone.

For many new astrophotographers, another common entry point into imaging is with something like an off-the-shelf DSLR or bridge camera with a stock wide-angle lens.

This kind of kit, combined with a normal photographic tripod, is a brilliant way to start capturing basic portraits of the Milky Way.

Particularly if the lens is fast – that is, if the f-ratio it can achieve when the lens aperture is set wide open is relatively low, say in the region of f/2–3 or thereabouts.

A 30-second exposure using a medium-to-high ISO setting – say 1600 to 6400 – with such a setup will bring out great detail in rich star fields and silhouetted dust lanes of the Milky Way from a dark site.

Beyond widefield Milky Way nightscapes, though, the challenge with shooting with a static tripod is that if you want to use a longer exposure – to go deeper and capture more faint details – you run into the problem of the sky rotating and stars trailing.

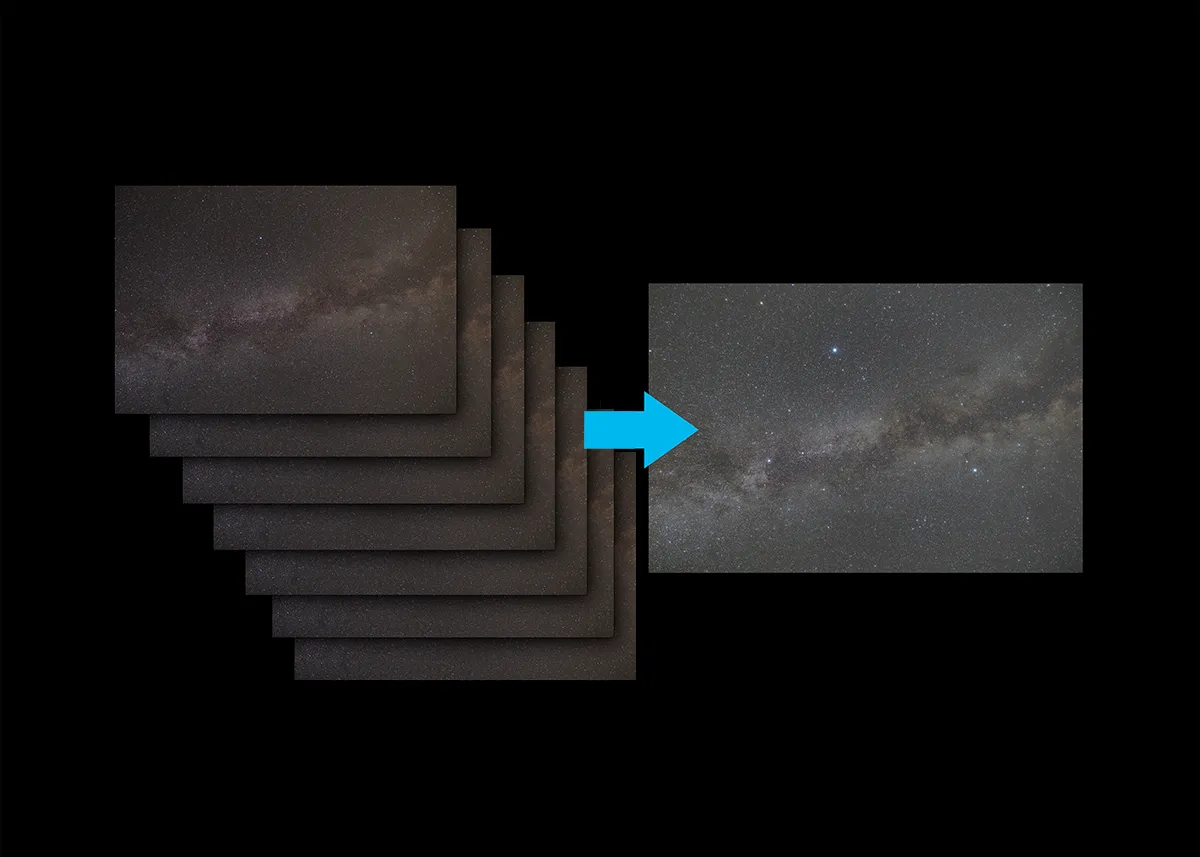

You can get around this by taking shorter exposures and stacking them in software to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

And then doing some clever compositing using layer masks, if you’re shooting with a landscape in the frame).

Another approach is to progress to mounting or piggybacking your camera on a driven telescope mount or a smaller, portable tracking mount.

Find out more with our guide on how to use a DSLR camera and DSLR astrophotography.

Using a tracking mount

Using a tracking mount for Milky Way photography allows you to do two things.

First, it enables you to drop down to a slightly lower ISO setting while dialling up the exposure length, so any resultant single image is less noisy – particularly useful for nightscapes.

Secondly, it opens up those much longer exposures more generally – we’re talking several minutes at a time here – because now the mount is cancelling out Earth’s rotation and keeping the stars point-like.

With this, you can then take multiple long-exposure sub-frames and stack them together to create detail-rich, deep, widefields of the Milky Way star fields or areas embedded within them.

The big variable once you get to this type of Milky Way photography, then, is the focal length of the lens you’re using.

You can find out more about this in our guide to using a star tracker DSLR mount for astrophotography.

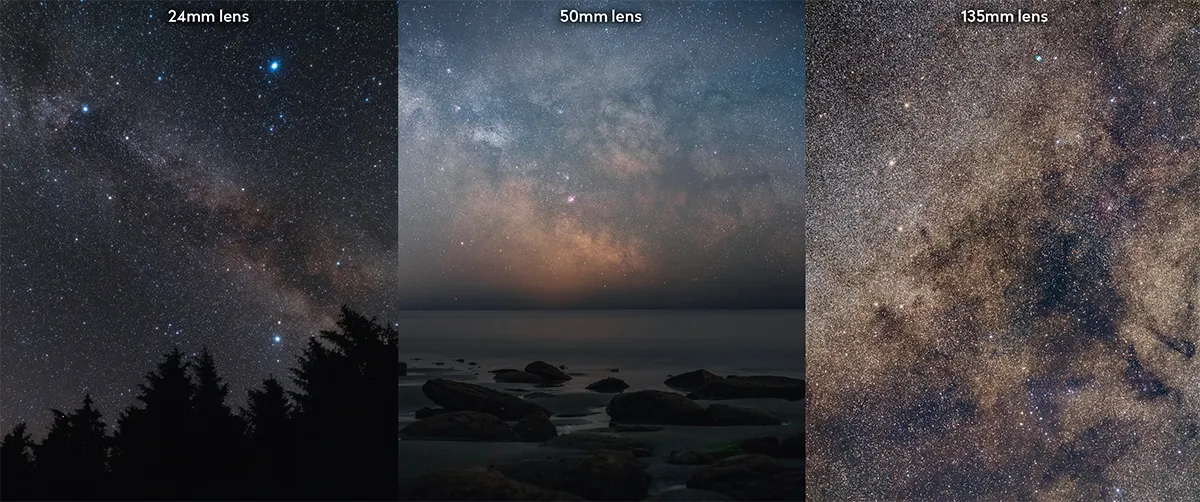

In the collage above, we’ve highlighted three examples of Milky Way imaging styles at different focal lengths.

A 24mm lens gives us a big field of view to work with on a full-format DSLR, which is ideal for wide shots of large swathes of the band of the Galaxy, both on a static tripod or tracking mount.

The 50mm lens, meanwhile, can be used for slightly more focused nightscapes on a particular area of the Milky Way, in that case the Galactic core.

But it’s also a great focal length for capturing deep images of dark dust lanes weaving through the Milky Way’s granular spiral arms or prominent constellations through stacking multiple exposures.

The last image was taken using a 135mm lens.

Focal lengths of 100mm upwards naturally provide much narrower fields of view, so they are best suited to putting deep-sky objects, like star clusters and nebulae, in the context of broader Milky Way star fields.

The summer and autumn skies in particular provide a wealth of targets for this kind of work.

How to plan your Milky Way shots

Before you go anywhere near the camera shutter button, spend some time planning the composition of your Milky Way images, whether they’re nightscapes or more complex captures using a driven mount.

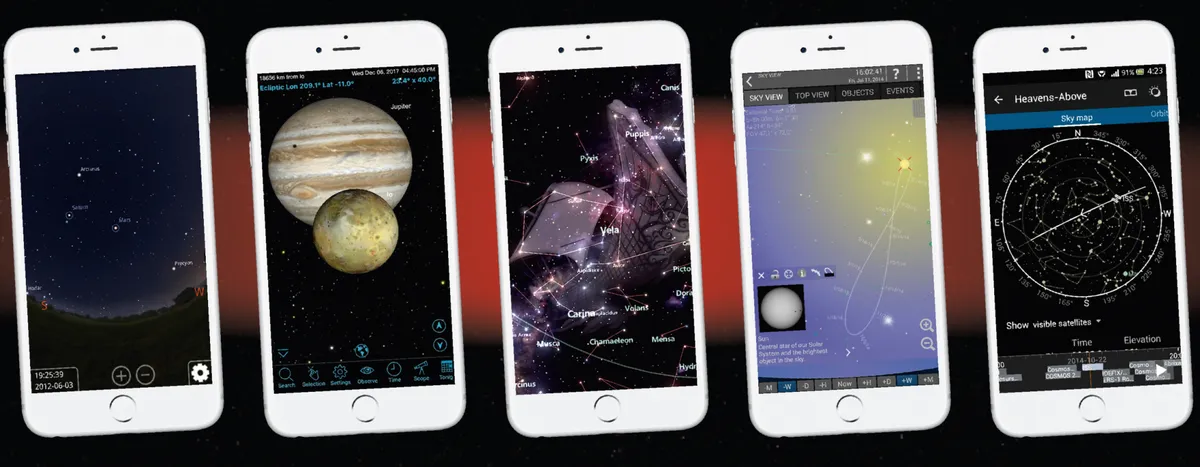

Software and apps – such as The Photographer’s Ephemeris, Stellarium and SkySafari Plus – will show you where the band of the Milky Way will be in the sky at what time.

The last two also have camera field of view tools that can help you scope out framings with your chosen kit.

Read our guide to the best smartphone stargazing and astronomy apps.

Settings

With so much variation in the kind of equipment you could use to shoot the Milky Way, it’s not possible to give a ‘standard’ starting exposure length or ISO setting to use.

Instead, the way I’d recommend approaching it is through experimentation, trying to find a good balance between the aperture setting of the lens, the exposure length and the ISO value.

For example, opening the lens aperture right up will gather more light, yes, but it will also, on most models, result in more obvious artefacts like the dimming of the corners and frame edges, known as ‘vignetting’.

It can also exacerbate star distortion around the edge of the frame.

Set the ISO too high or too low and you either bring in a lot of noise or don’t get the detail you need.

And then there are the sky conditions, like light pollution and transparency, whose variable effects you’ll need to factor into these considerations.

Capturing the data is only part of photographing our Galaxy, however.

The post-processing of that imagery is where it can really come to life.

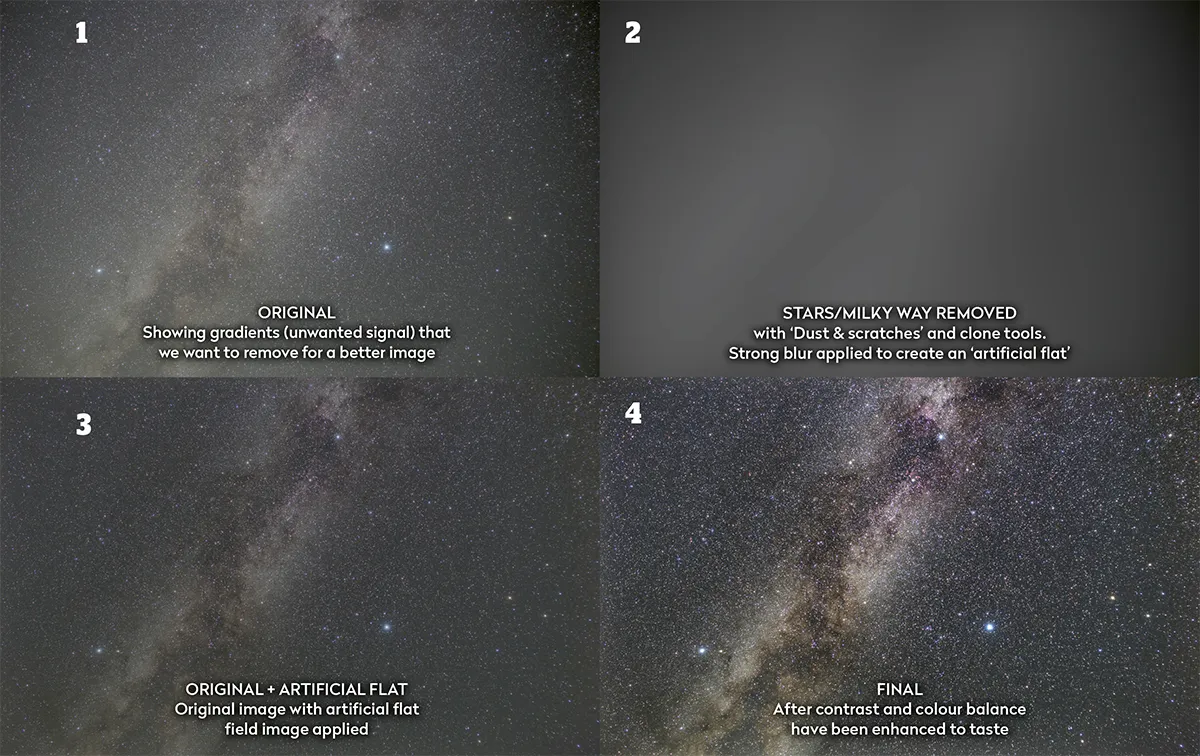

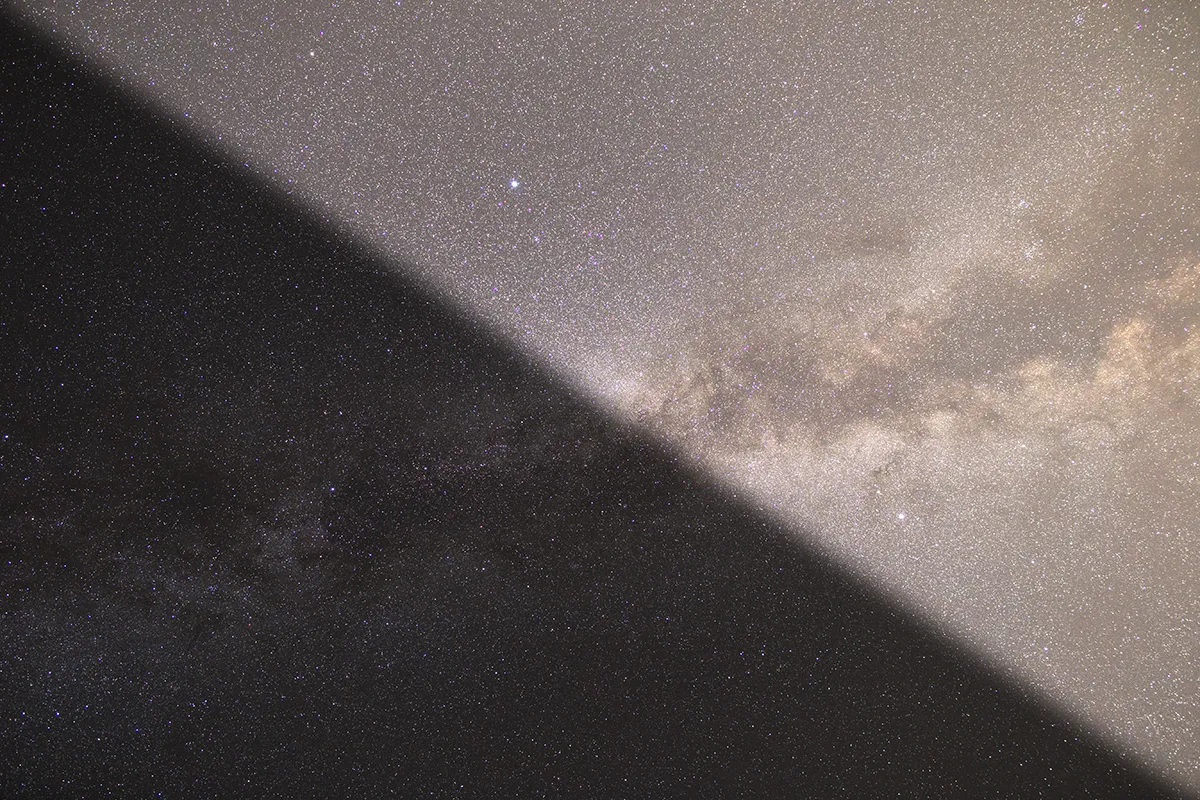

We’ll get onto image processing in a moment, but for widefield Milky Way work there’s one common problem that often comes up: gradients, either from the optical system or from light pollution in the sky, or often both.

Gradients

To tackle vignetting, you can take some very – and I stress very – rudimentary flat fields by focusing the lens at infinity and then taking some well-exposed images of a smooth, plain and evenly illuminated white interior wall, which you can use to calibrate data in stacking software later.

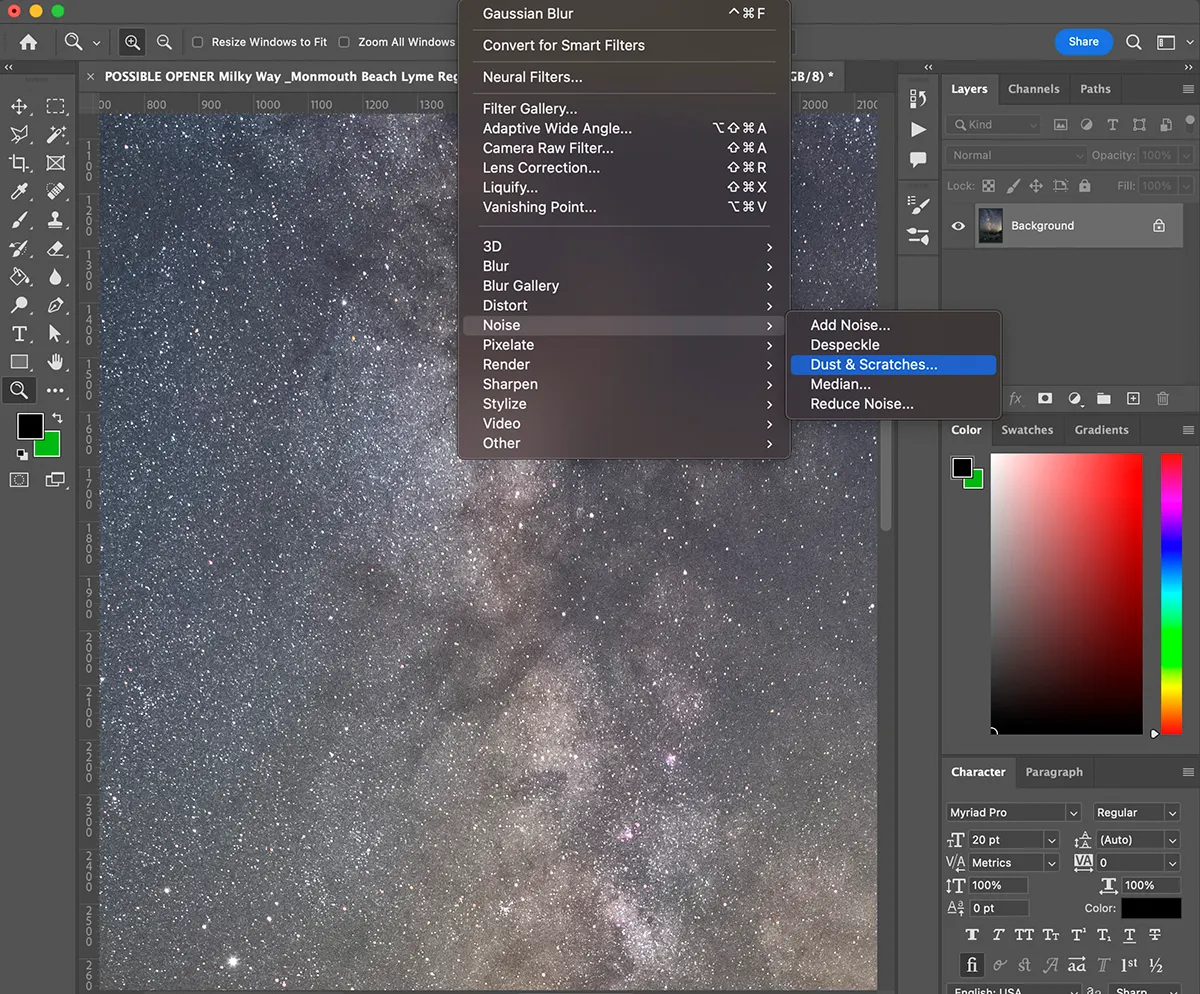

If the astronomical processing software you’re using doesn’t have a built-in gradient removal tool for any remaining gradients, here’s one way to tackle moderate gradients in a program like Photoshop: first duplicate your image as a new layer.

Then use a ‘Dust & scratches’ removal tool to remove all the stars.

Then clone out, with the clone or heal tool, any remaining bright stars and Milky Way features in view.

Next apply a fairly strong Gaussian blur to the centre 80–90% of the frame using a marquee tool and then ‘Select and mask’, followed by the blurring filter.

Now place this image in the layer below the original image layer and use ‘Image > Apply image’ with the blending mode set to ‘Subtract’. Copy the resultant image into a new layer and process it to taste.

Create your Milky Way image, step-by-step

Step 1

To fully capture the incredible granular Milky Way star fields, it’s crucial to devote time to getting the focus spot on.

If you’re using a live preview screen for focusing, don’t use stars around the periphery of the frame to focus on, as often with wide-angle lenses optical aberrations make it harder to perceive the exact focus point.

Step 2

If you haven’t already done so, plan your composition in planetarium software (eg Stellarium).

Now set your camera to a very high ISO and use short exposures to capture some test shots.

For this kind of image it’s best not to include any earthly foreground, unless you are happy with it being blurred when we stack frames later.

Step 3

Change the ISO and exposure length to the settings you need to capture your sub-frames.

These will be the level at which there’s a good balance between the amount of detail you’re getting in the star fields and the ‘fogging’ effect of any light pollution at your site.

There’s no one-size-fits all, so experimentation is key.

Step 4

With a suitable exposure length and ISO selected, capture at least 10–15 minutes’ worth of data in total when shooting your main data.

More sub-frames to stack later will help you create a smoother final image, something that’s especially important if you’re shooting at a high-ISO setting on a static tripod.

Step 5

Once you’re back home, consider if you’ll need some ‘flat field’-style calibration frames with the lens you used (see opposite for more details).

When you have your data loaded onto your computer, inspect each sub-frame carefully and set aside any that show signs of cloud passing through the shot, mount vibrations or wind blurring.

Step 6

You should now have a folder of image files that you’ve inspected that represent the best frames from your capture sequence.

You can now add, or stack, these together in dedicated astronomical processing software, whether that be free programs like DeepSkyStacker or commercial options like Nebulosity or PixInsight.

Step 7

A good first step is to enhance the contrast and brightness of your stacked shot via a gentle Levels or Curves ‘stretch’.

Using the Curves tool in a program like Photoshop, adjust the diagonal line so that it takes on a subtle ‘s’ shape, bringing up the brighter elements of the image while increasing the contrast in the shadowier parts.

Step 8

If the post-processing software you’re using doesn’t have gradient or vignetting removal tools, you can do basic gradient removal using the technique outlined opposite.

You may then want to return to step 7 to do another round of contrast and brightness enhancements (on the hopefully now-improved image) .

Step 9

Finish with basic colour balancing of your picture. Look for bright(ish) stars in your framing that have a neutral white spectral type (using software like Stellarium as a reference).

Then use a colour balance tool in your processing software to adjust the picture’s overall colour so that the stars’ hue is as close to neutral white as possible.

Have you captured an image of the Milky Way? Don't forget to send us your images.

This article originally appeared in the May 2023 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.