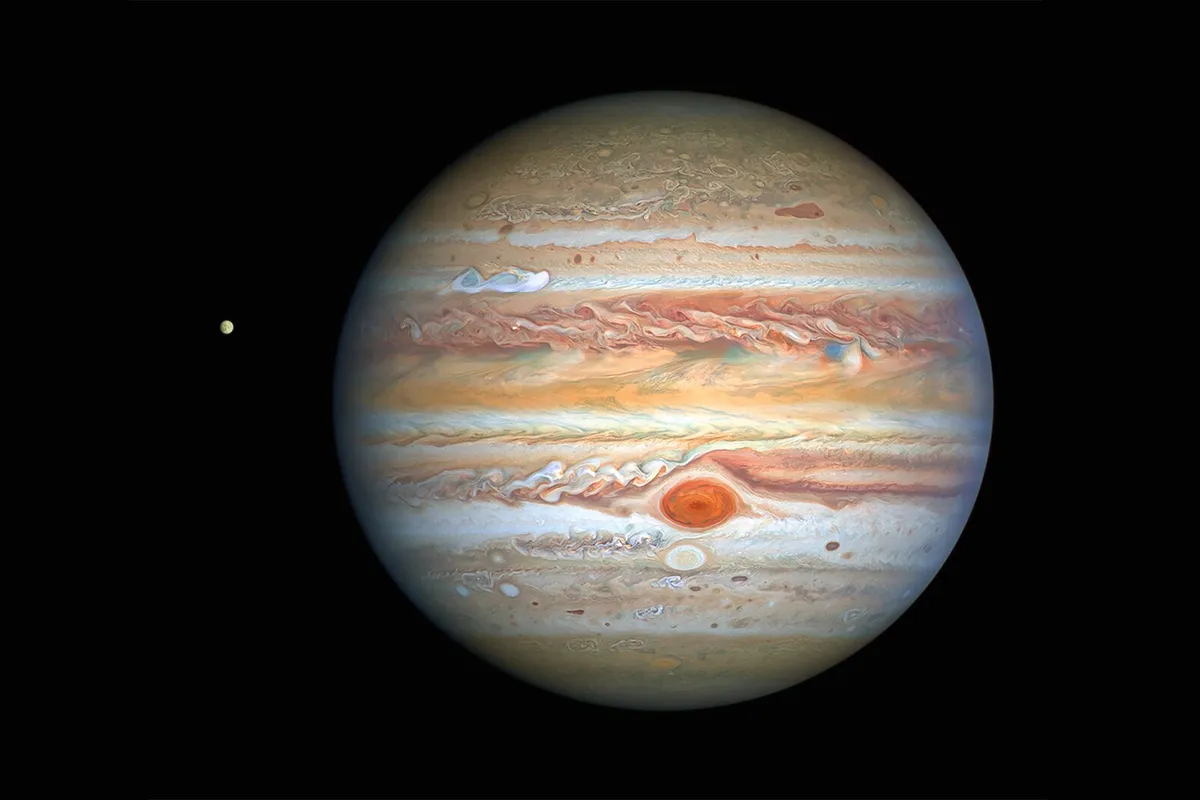

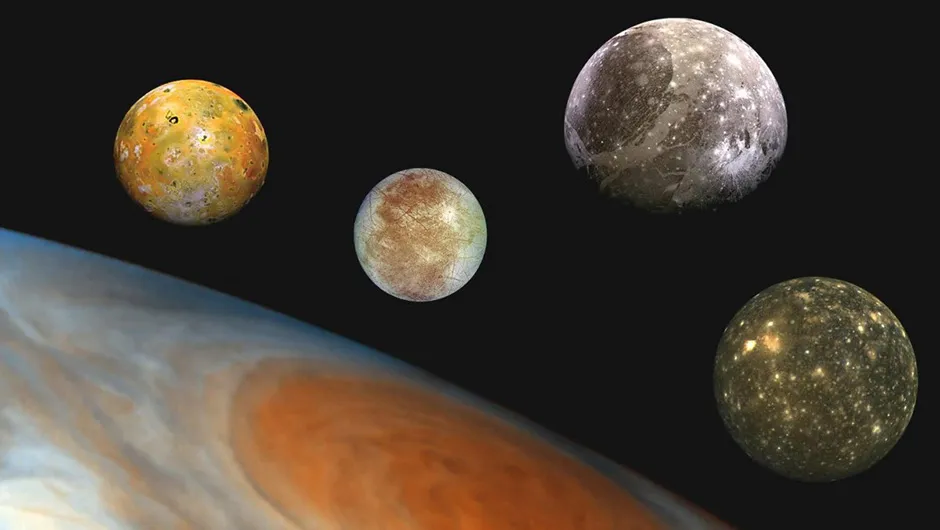

Jupiter's Galilean moons are its four largest satelilites Io, Callisto, Europa and Ganymede.

They're known as the Galilean moons because the first recorded observation was by Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei in 1610.

The Galilean moons are fascinating worlds. Ganymede, for example, is the largest moon in the Solar System.

Io is the most volcanically active world in the Solar System, its volcanoes having been discovered by planetary scientist Linda Morabito during the Voyager mission.

Want to explore Jupiter's Galilean Moons for yourself? Read our guide on how to observe Jupiter through a telescope

Europa is an icy moon with a subsurface ocean lurking beneath its frozen crust, much like Saturn's moon Enceladus.

As a result, it's one of the best places in the Solar System to search for conditions that could support life.

Callisto is the third largest moon in the Solar System, after Saturn's moon Titan, and may be considered by some to be the lifeless, characterless member of the four Galilean moons.

However, there is evidence that Callisto too hosts a subsurface ocean. Could it be another contender for life-supporting conditions beyond Earth?

How the Galilean moons formed

It is thought that Jupiter's largest moons Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto most probably formed out of material leftover from the formation of Jupiter itself.

Like the rest of the Solar System planets, Jupiter formed out of the disc of dust and gas surrounding the young Sun. Once this gas and dust had condensed to form Jupiter, the leftover material coalesced and grew over time to form the Galilean moons.

This makes Jupiter's largest moons likely as old of the rest of the Solar System: about 4.5 billion years old.

Observing Jupiter's Galilean moons

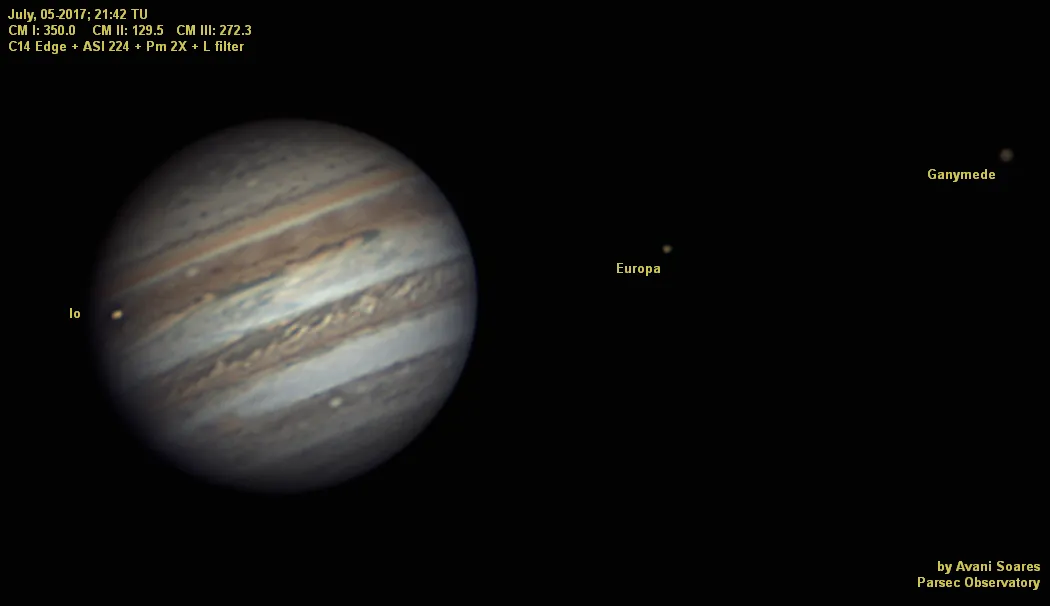

The Galilean moons are also a favourite target of astronomers because it is possible to view them around Jupiter, provided you have a big enough telescope.

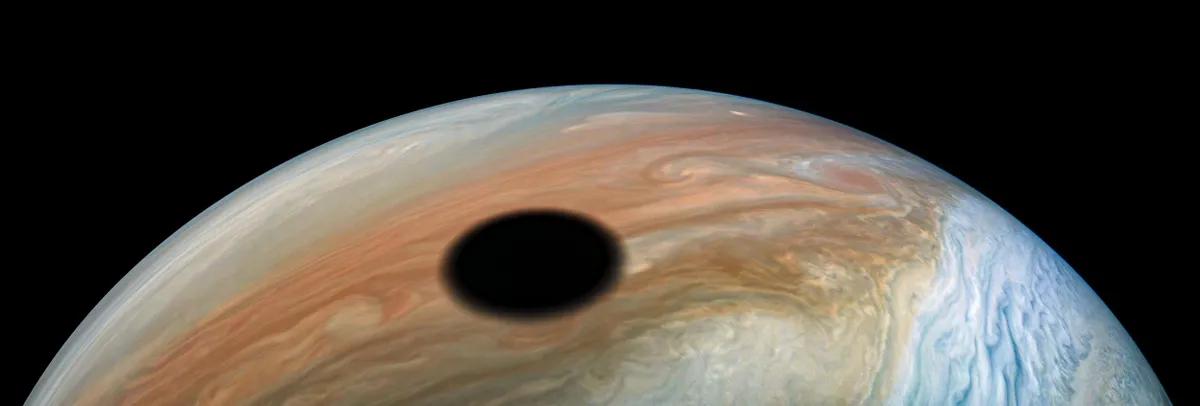

If you know when and where to look, you may be able to see transits of the moons passing Jupiter, spot their shadows cast on the gas giant's surface, or even an occultation.

Find out more about observing the Galilean moons.

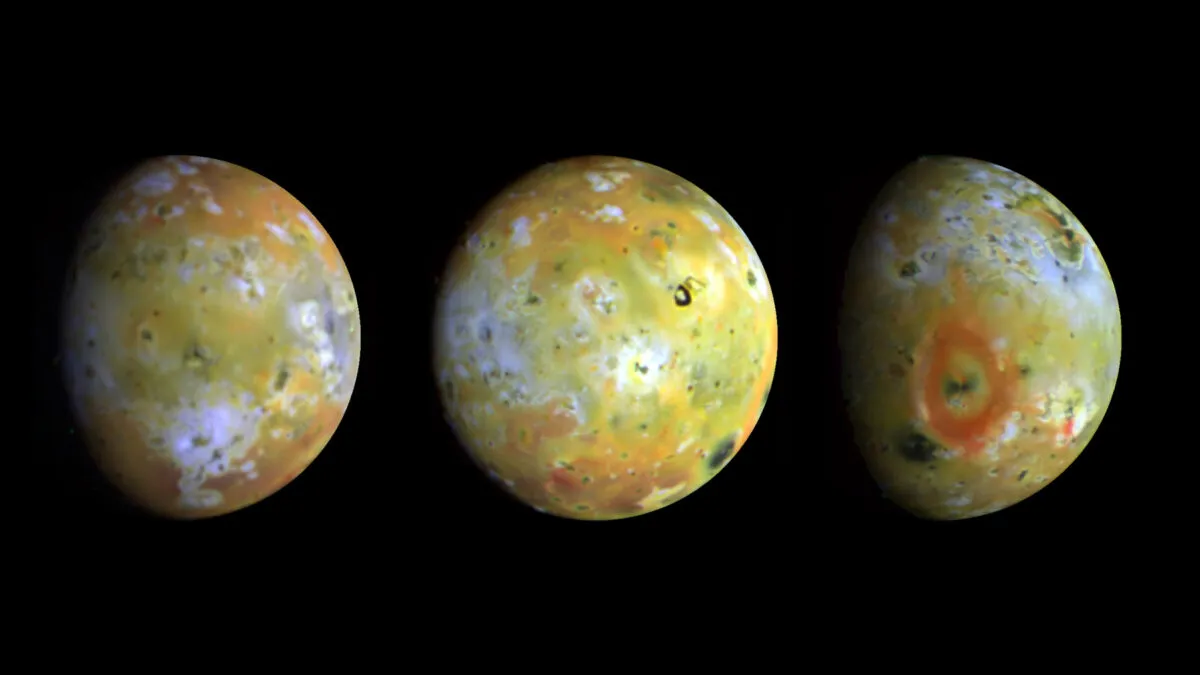

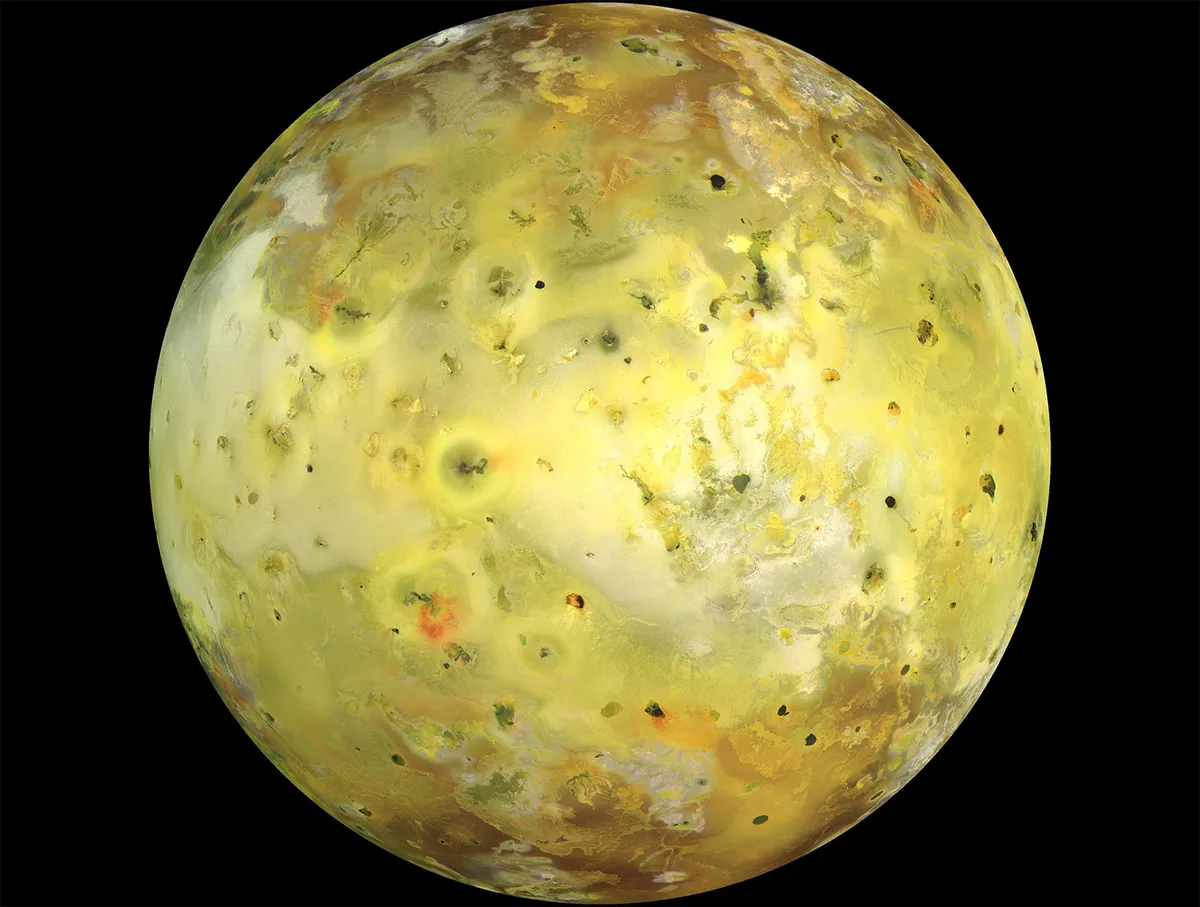

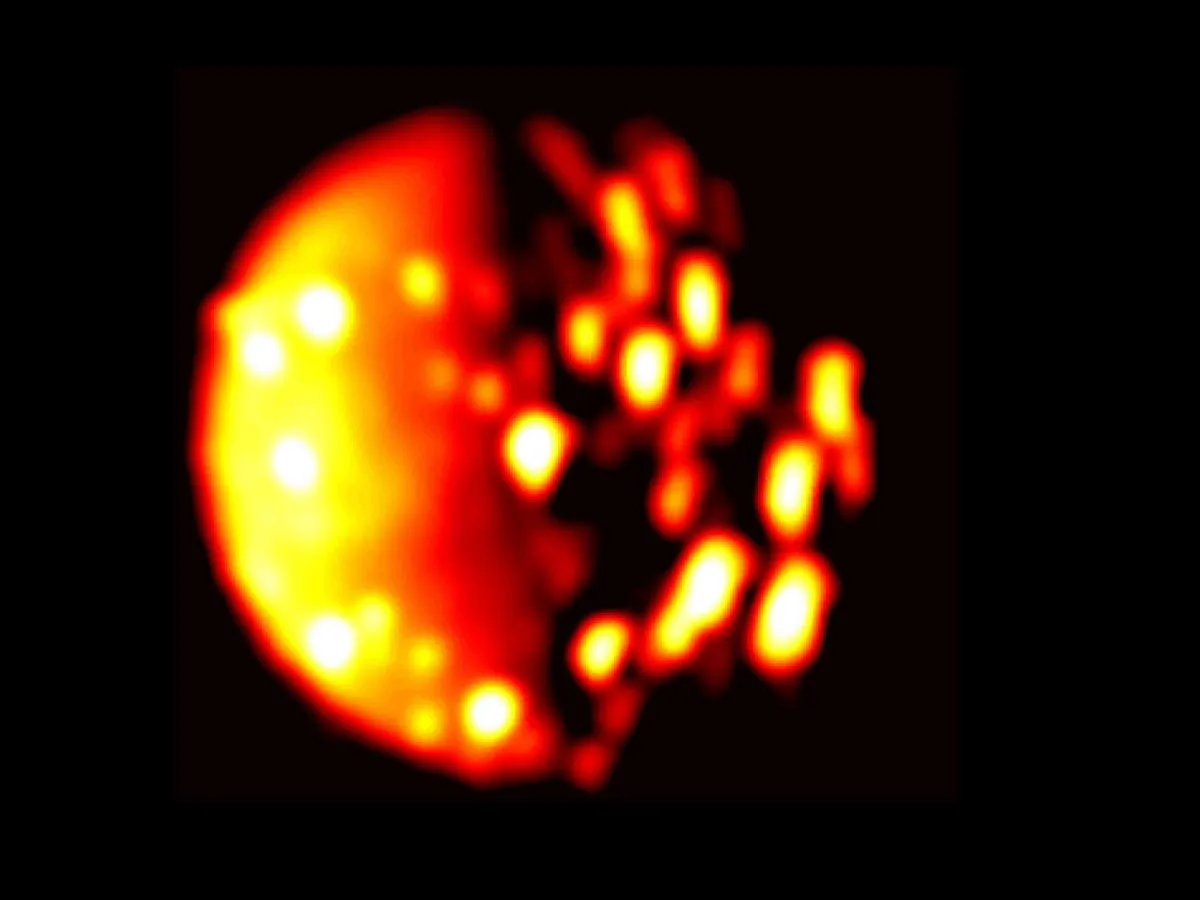

Io

- Diameter: 3,660km

- Mass: 0.015 Earth masses

- Orbital distance: 421,800km

- Equatorial circumference: 11,445.5km

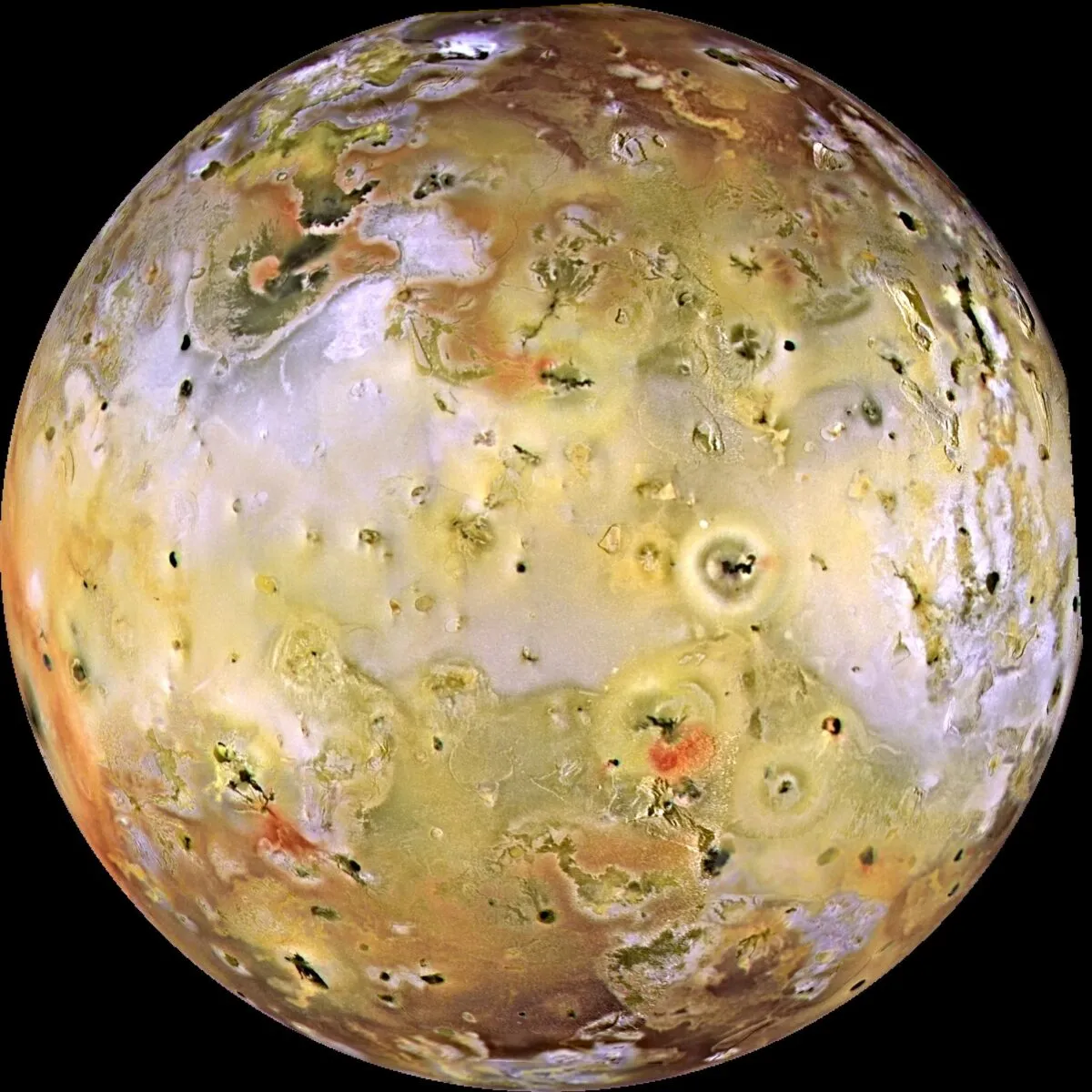

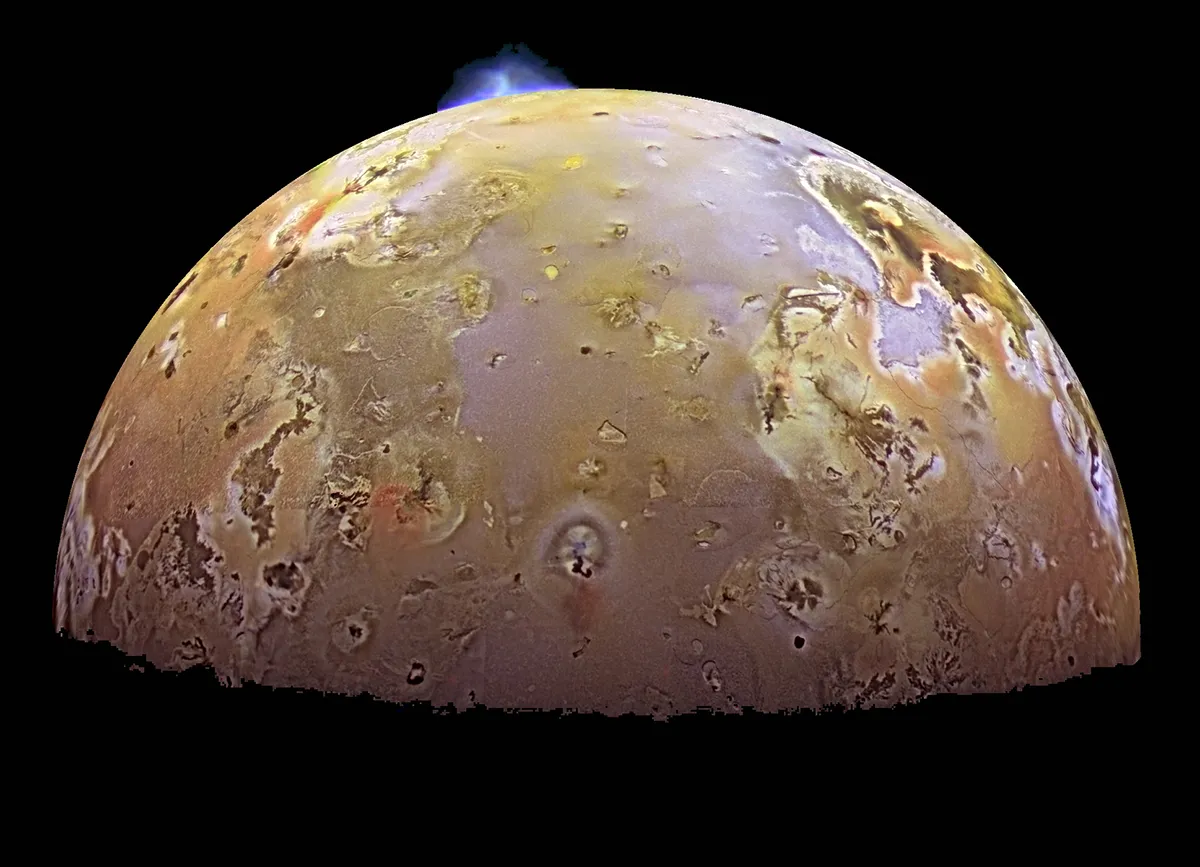

Io is the most volcanically active body in the solar system, hosting hundreds of volcanoes that are kept active by the gravitational interactions between the moon, Jupiter, and fellow Jovian satellites Europa and Ganymede.

It has a highly elliptical orbit, and tidal forces generated through its interaction with Jupiter generate a fierce amount of heat that causes molten lava to spew from volcanoes, filling surface impact craters.

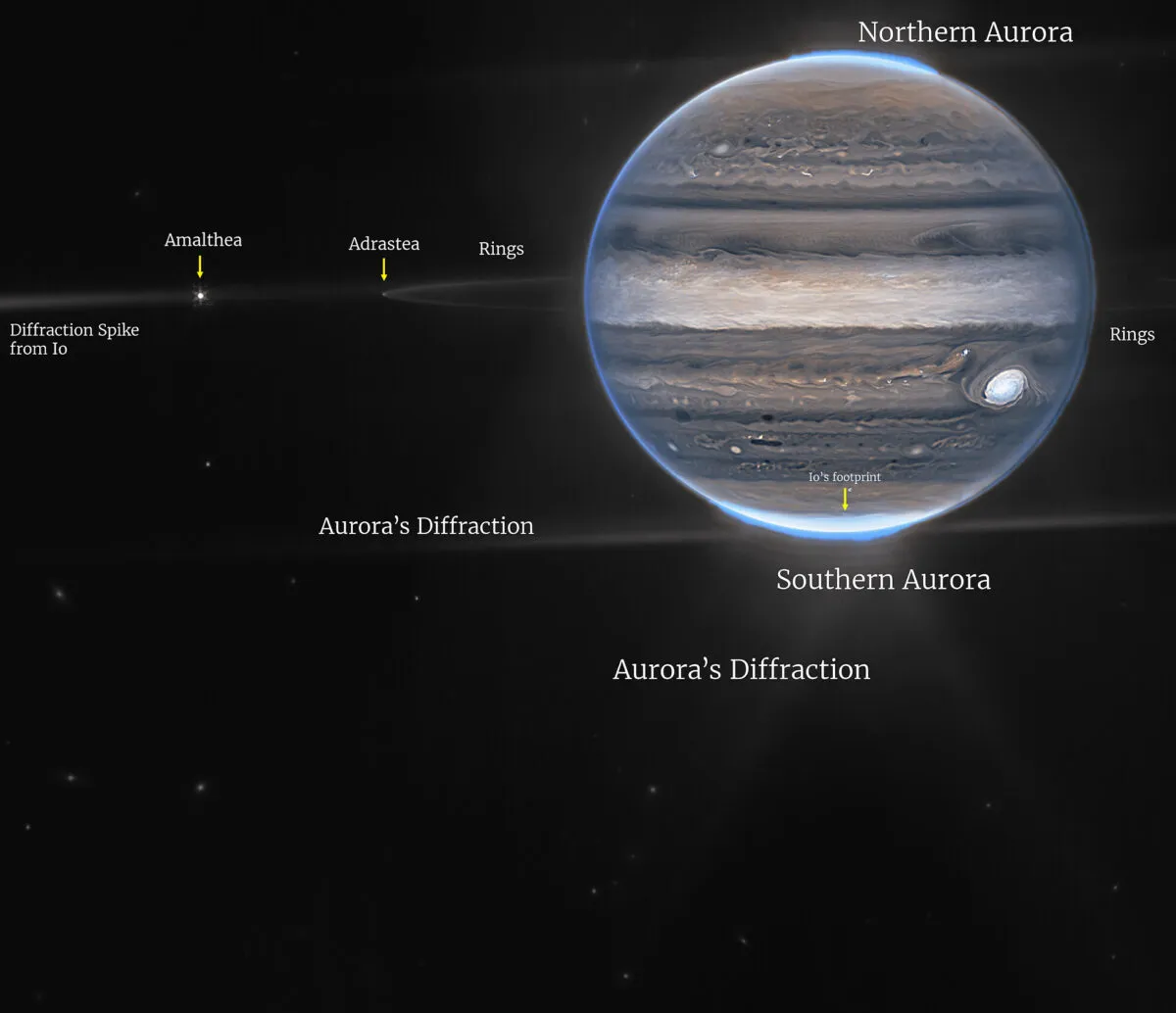

Jupiter's magnetic field strips material from Io's surface, producing a cloud of radiation around the volcanic moon.

As a result of all these processes, Io is an incredibly dynamic world, and perhaps one of the oddest looking moons in the Solar System.

According to Linda Morabito, when Voyager scientists got their first glimpse of Io, they described it as looking like 'mouldy pizza'.

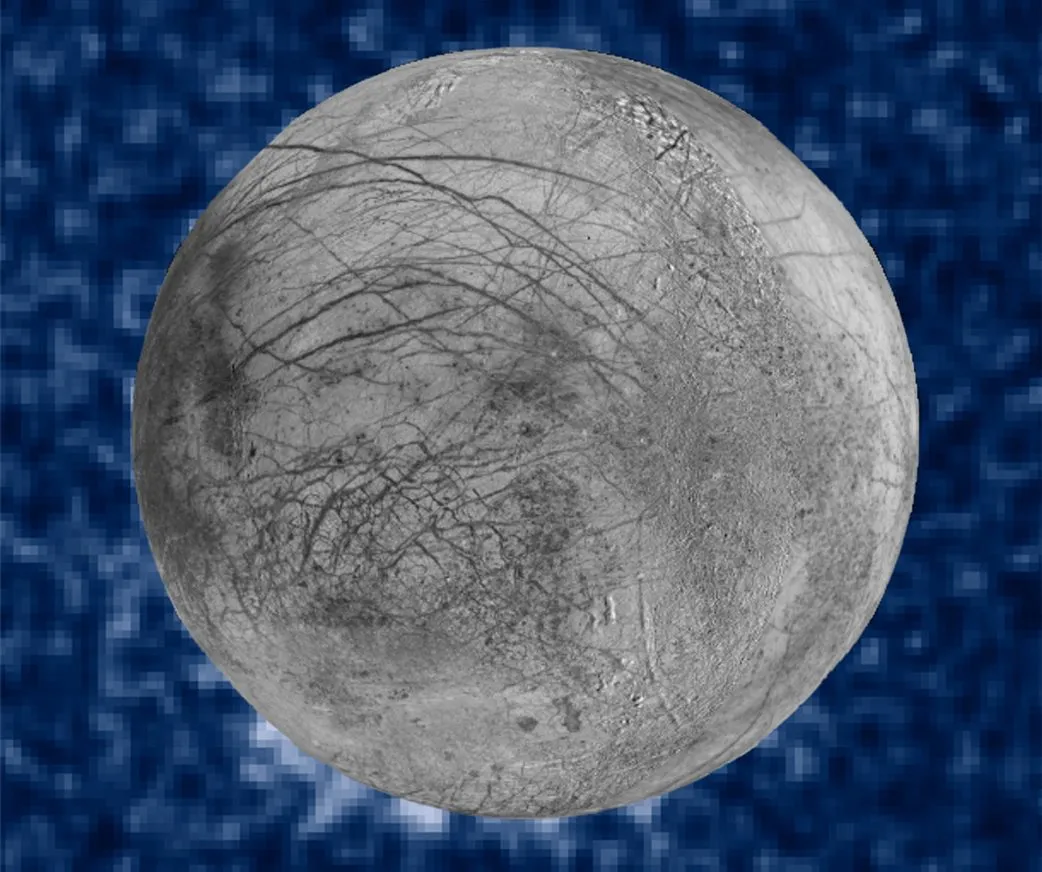

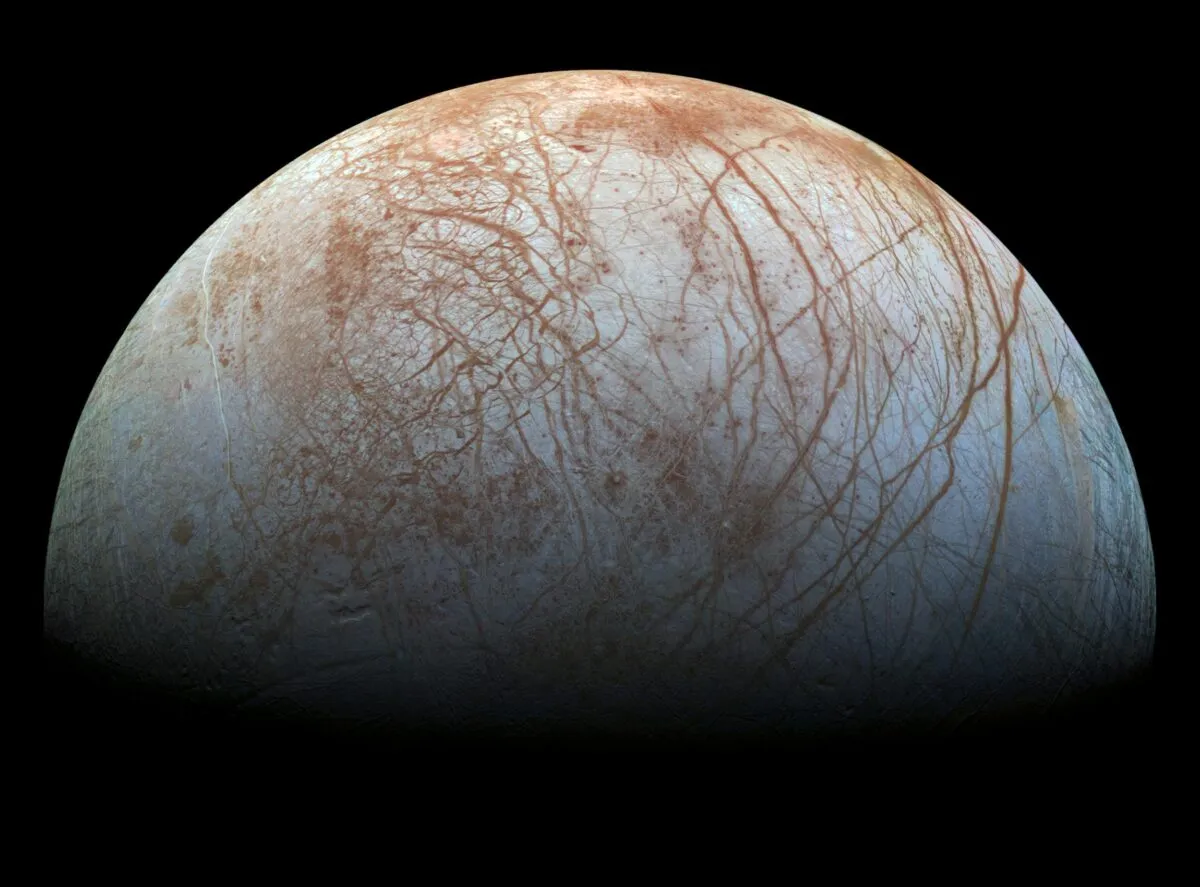

Europa

- Diameter: 3,122km

- Mass: 0.008 Earth masses

- Orbital distance: 670,900km

- Equatorial circumference: 9,807km

The smallest of the moons, Europa is an icy world known to have a liquid ocean beneath its 15-25km thick icy crust, which may contain twice as much as all of Earth's oceans combined.

This makes it a promising place to search for life, and this is exactly what missions JUICE - JUpiter ICy moons Explorer - and Europa Clipper will be doing.

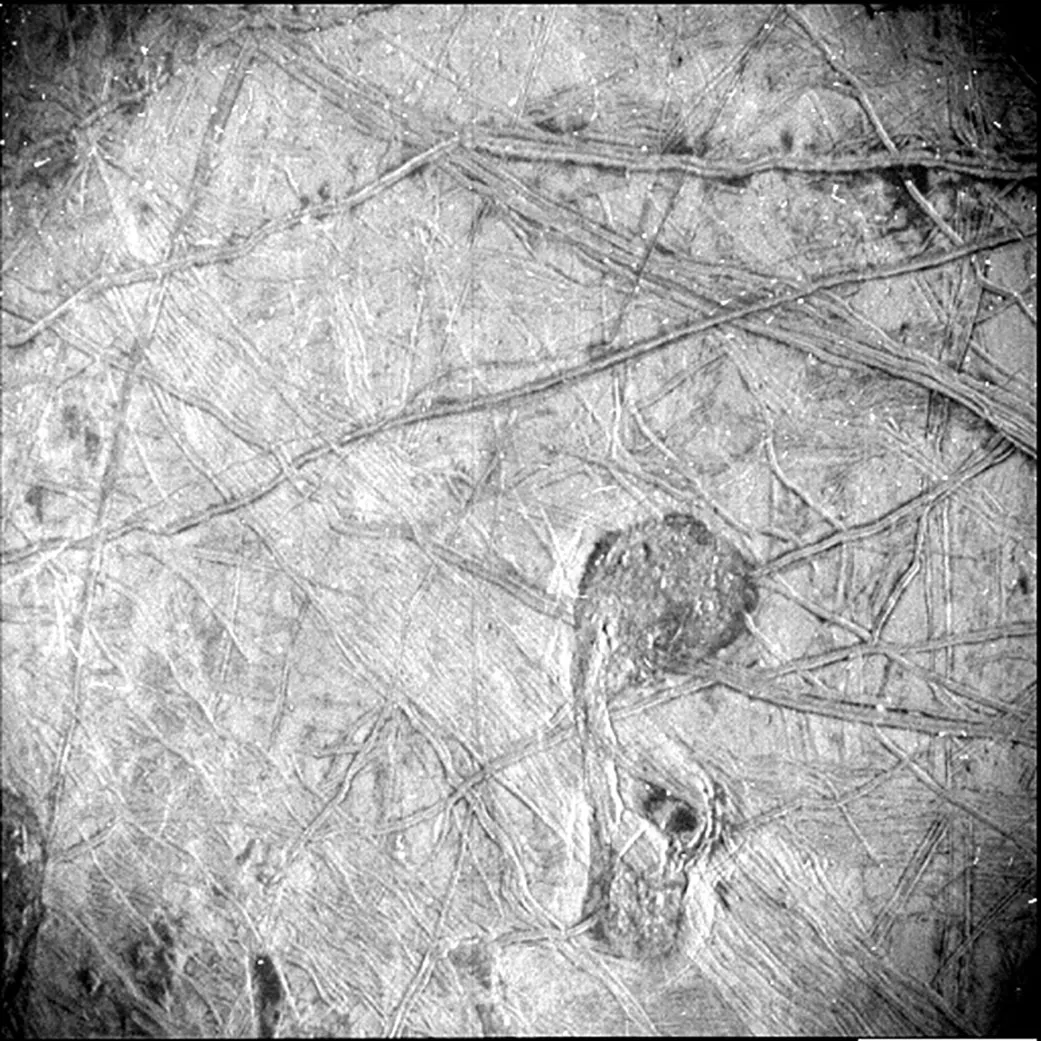

Images of Europa reveal long, linear fractures and rusty red-brown material that could be salty, sulphuric compounds that have mixed with water ice and been blasted by radiation.

Its surface is young, potentially as young as 40 million years old, which is evinced by the very small number of craters that can be seen.

Studies using the Hubble Space Telescope have revealed that Europa might actually be venting water from its subsurface ocean out into space, which would be prime targets for future missions to explore Europa, just like the Cassini spacecraft at Saturn's moon Enceladus.

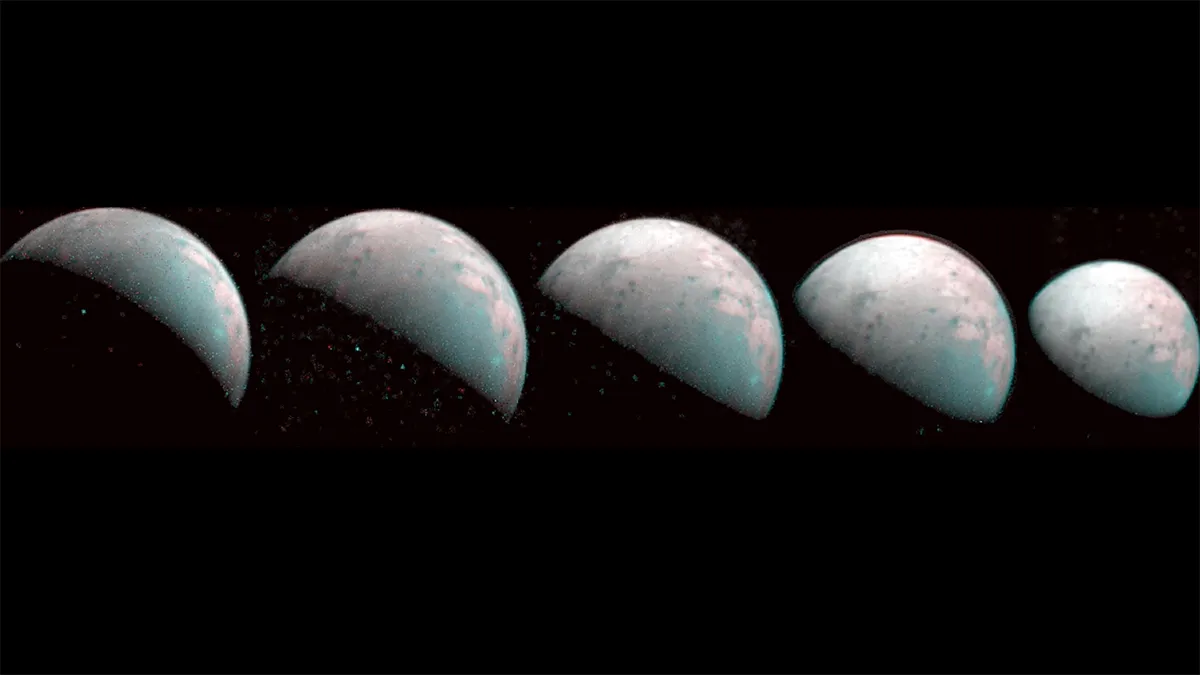

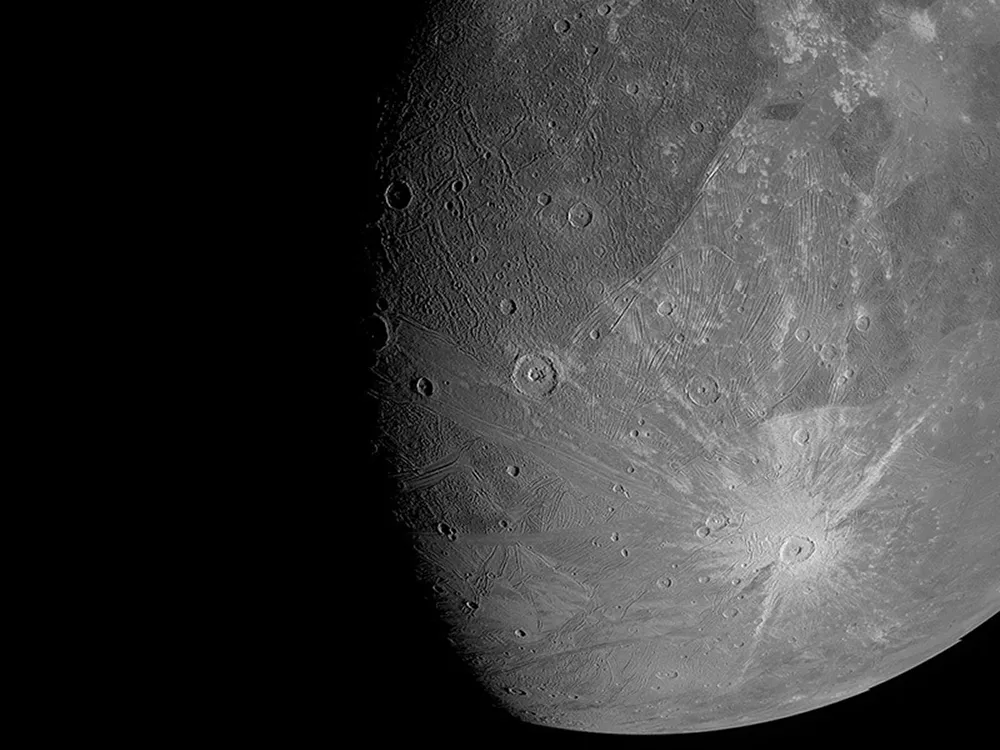

Ganymede

- Diameter: 5,268km

- Mass: 0.025 Earth masses

- Orbital distance: 1,070,400km

- Equatorial circumference: 16,532km

Ganymede is quite a specimen. It's the largest moon in the Solar System and the only moon orbiting the Sun with its own magnetic field. As a result it has aurorae at its north and south poles.

It is thought to have a large rocky core covered with layers of ice and water, which show signs of tectonic activity.

The surface of Ganymede seems to have two types of terrain: dark cratered areas and lighter terrain sporting cracks and grooves.

These grooves can stretch 700 metres high and could be a result of tensional faulting, or it could be that Ganymede has a subsurface ocean that's releasing water into space.

Callisto

- Diameter: 4,821km

- Mass: 0.018 Earth masses

- Orbital distance: 1,882,700km

- Equatorial circumference: 15,144km

Callisto is Jupiter's second largest moon and perhaps the dark horse of the Galilean satellites. It seems to be a geologically inactive, dark, cratered world, but planetary scientists believe it could host a liquid ocean beneath its surface.

That's not to diminish what's going on at the surface, however. Callisto's surface is about 4 billion years old - a result of its geological inertness - and thought to be the oldest, most cratered surface in the Solar System.

The bright spots that pepper Callisto's surface might well be water ice, frozen on the peaks of its many craters.

Callisto's subsurface ocean could be interacting with a layer of rocks 250km deep, and oxygen has been detected in the moon's exosphere.

Could Callisto be a key player in the search for life in the Solar System?

Discovery of the Galilean moons

On the title page of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius (Sidereal Messenger) – the first astronomical work based on telescope observations when it was published in 1610 – the author says that the book introduces the reader to "great and surpassingly wondrous sights… observed by Galileo Galilei, Florentine patrician and public mathematician at the University of Padua… in four planets revolving with remarkable speed at differing distances and periods around the star Jupiter.

"They have been known to no one up to this day, and the author was the first to discover them. He has decided to call them the Medicean planets."

The initial naming of the moons as the Medicean planets was to acknowledge the patronage he received from Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici of Tuscany (1590–1621), whom Galileo had served as mathematics tutor in 1605.

Galileo’s first idea was to name the newly discovered moons the Cosmica Sidera (Cosmian Stars) solely in honour of his patron, but ultimately chose a name that honoured all four surviving Medici brothers: Cosimo, Francesco, Carlo and Lorenzo.

- Make your own Galilean telescope

Galileo also recognised that the four objects he had observed through his telescope were the first ever seen to orbit another planet, and the importance of his discovery was not lost on him.

But though he may have been the first to name them, Galileo’s claim to having been the first to see them has come under some doubt.

It has been suggested that the Chinese astronomer Gan De, who carried out some of the earliest known systematic observations of the planets in the 4th century BC, may have seen Ganymede.

It was while he was studying Jupiter during the summer of 365 BC that Gan De recorded what he described as a ‘small reddish star’ next to the planet.

The Chinese astronomy historian Xi Zezong (1927-2008) suggested this may have been an early sighting of Ganymede.

It is theoretically possible to see the Galilean moons with the naked eye, but it requires near perfect conditions and incredible eyesight.

In 1614, around four years after Sidereus Nuncius was published, German astronomer Simon Marius (1753-1625) published his work Mundus Iovialis (1614) in which he described the planet Jupiter and its moons.

He laid claim to having discovered them in December 1609.

This would mean that Marius had spotted the Jovian moons some time before Galileo who, according to Sidereus Nuncius, had first seen them on 7 January 1610.

However, what is certain is that Galileo was the first to publish what he saw.

It was on that date that Galileo turned his telescope towards Jupiter and noticed what he described as “three little stars… positioned near (Jupiter) – small but yet very bright” and noting the presence of a fourth ‘little star’ a few days later.

Although his first thoughts were that these were ‘fixed stars’, Galileo was sufficiently intrigued by the fact they were “arranged exactly along a straight line and parallel to the ecliptic” to continue his observations, which ultimately revealed their true nature.

After announcing the moons in Sidereus Nuncius, independent verification and sightings of the newly discovered Jovian moons came from a number of sources.

These included such noteworthy observers as Johannes Kepler in Prague, English astronomer Thomas Harriot and French astronomer Joseph Gaultier de La Vallette.

Regardless of who saw them first the mythological names by which these satellites are known today are those given them by Marius (inspired by a suggestion from Johannes Kepler).

In 1614, he wrote in Mundus Iovialis, “Io, Europa, the boy Ganymede and Callisto greatly pleased lustful Jupiter.”

However, the names didn’t gain favour until the early 20th century, mainly because Galileo refused to use them.

In the meantime, Jupiter's Galilean moons were generally referred to as Jupiter I, II, III and IV according to their closeness to Jupiter.

It would be another few centuries until Jupiter’s next moon, Amalthea, was discovered by American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard using the 36-inch Great Lick Refractor at Lick Observatory on 9 September 1892.

Amalthea holds the distinction of being the last planetary satellite to be discovered by direct visual observation.

The sixth Jovian moon, Himalia, was revealed on 3 December 1904 using astrophotography, as have all of its many subsequently discovered moons.

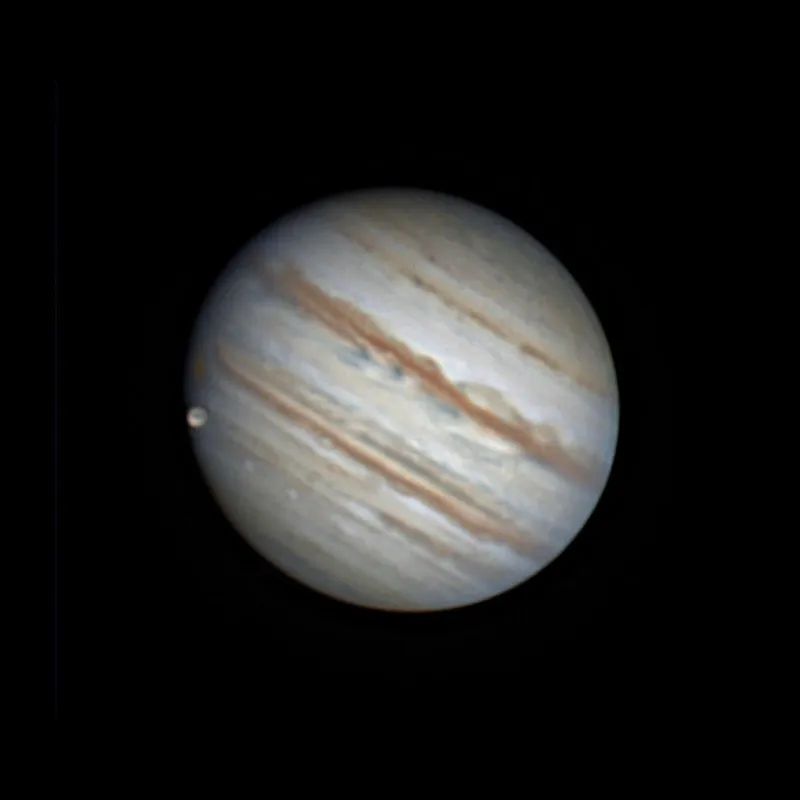

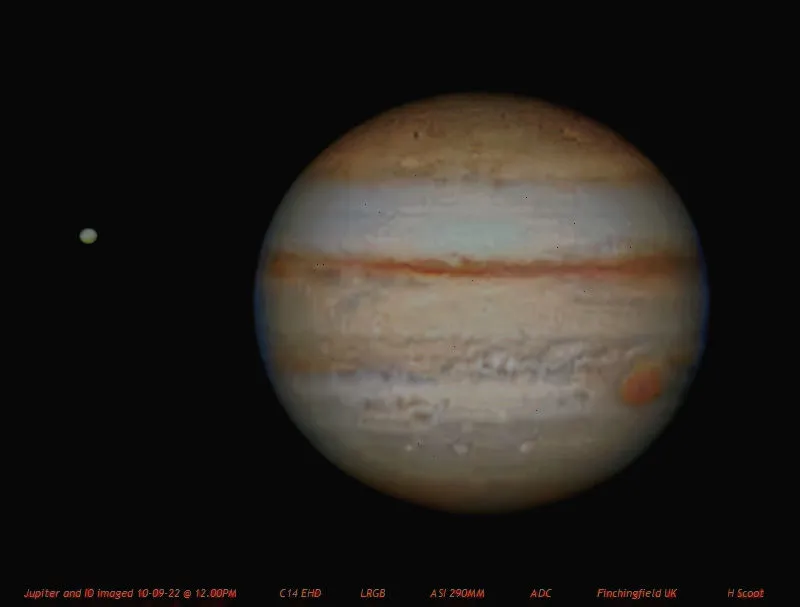

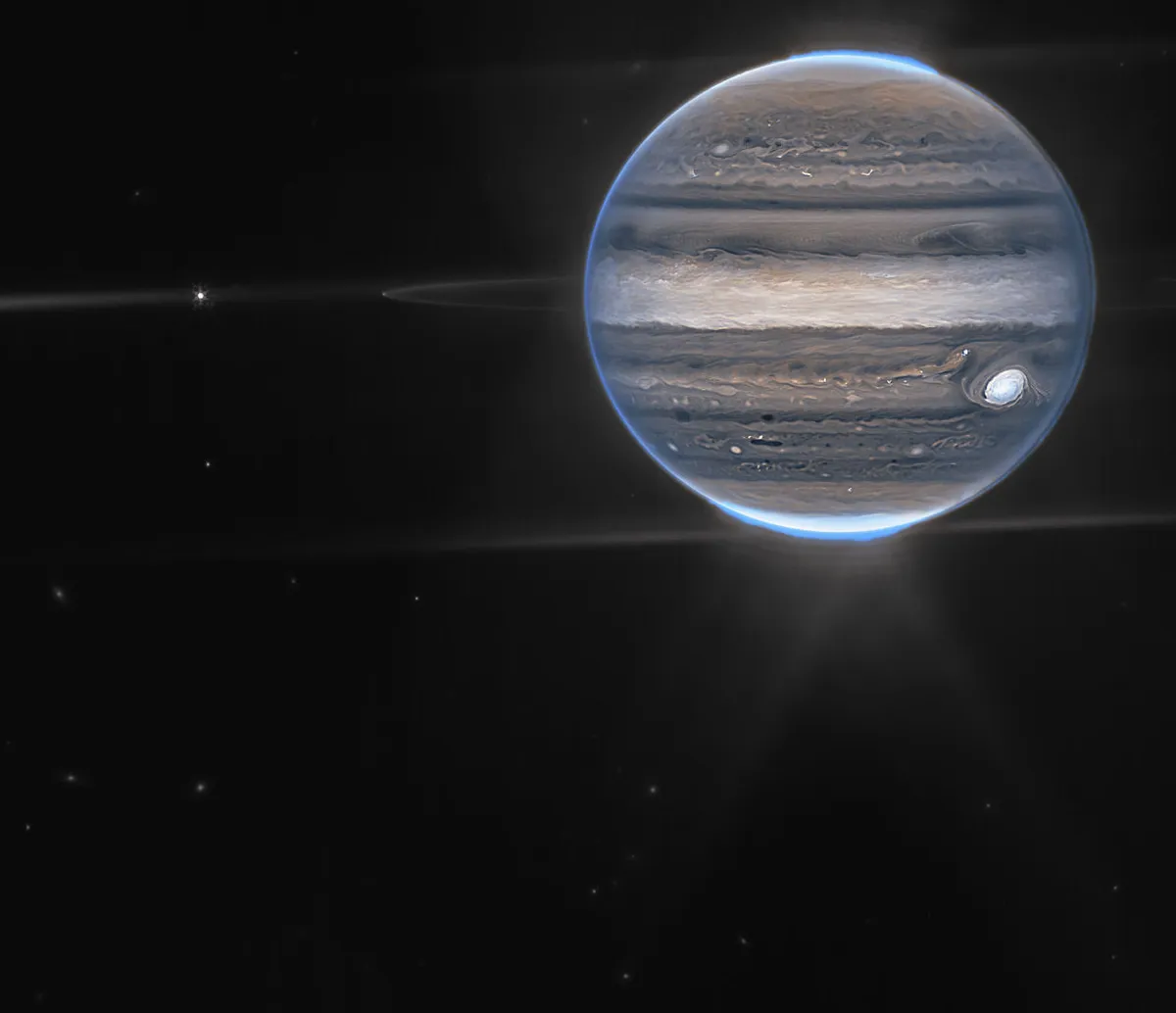

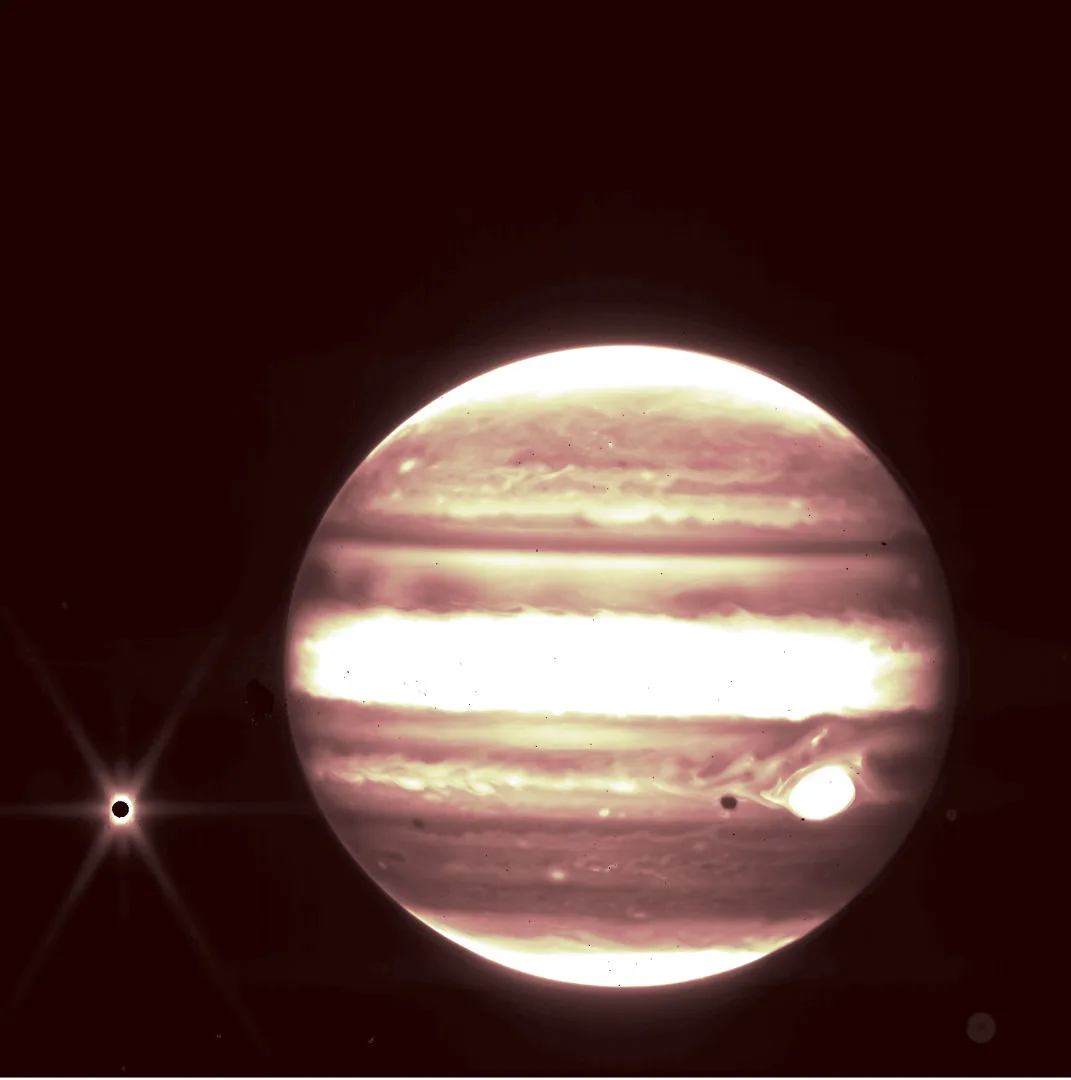

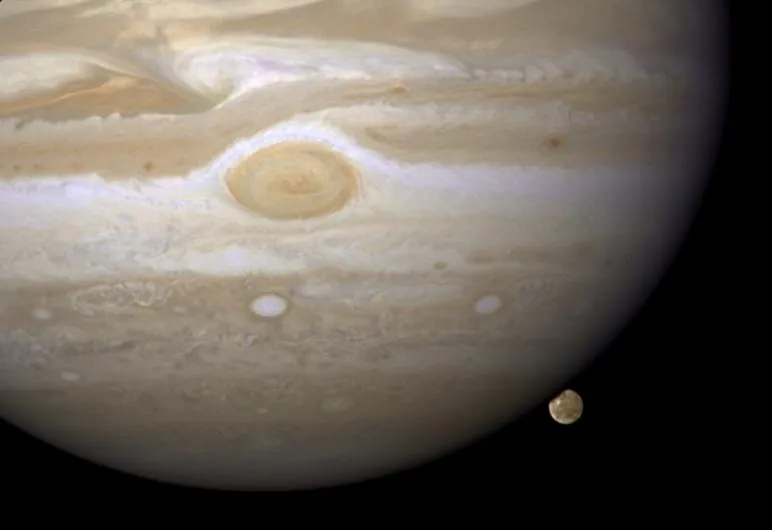

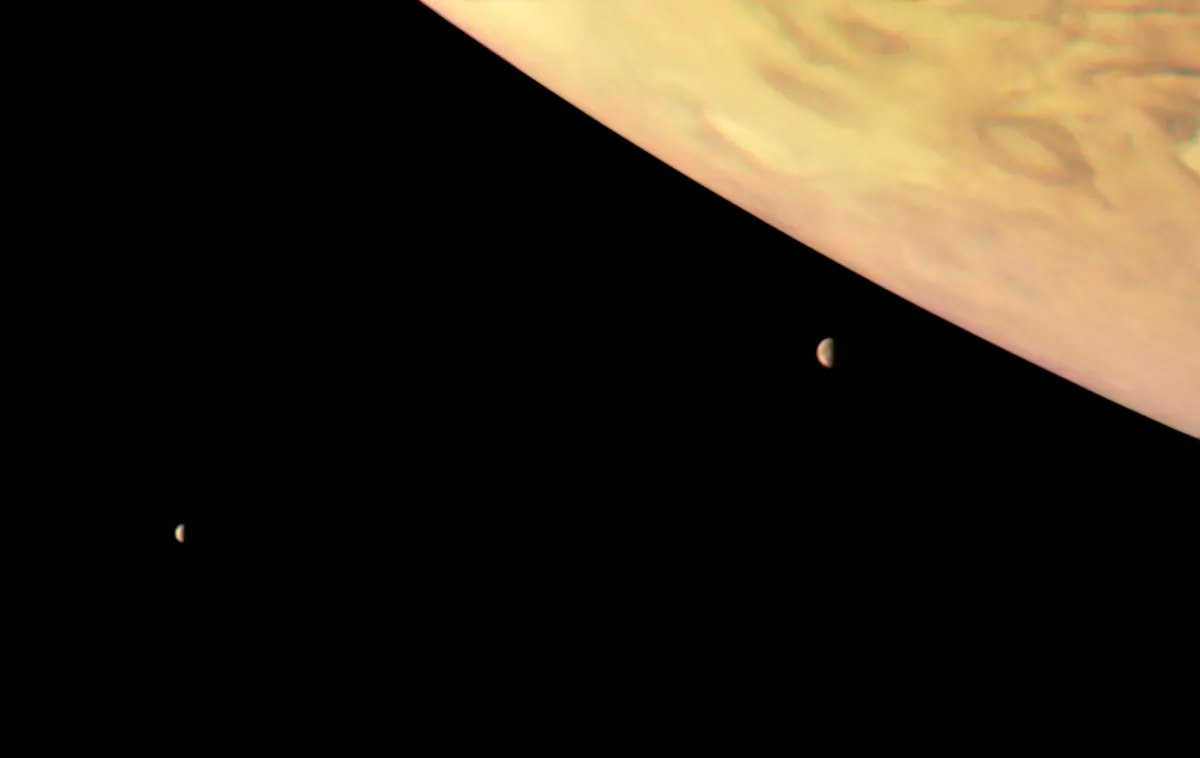

Photos of Jupiter's Galilean moons

Below is a selection of images of Jupiter and its four largest moons captured by astrophotographers and BBC Sky at Night Magazine readers.

For advice on photographing Jupiter, read our guide on how to photograph the planets. If you do manage to capture Jupiter and its Galilean moons, be sure to send us your images or share them with us via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.