In many ways, Venus and Earth are very similar. They are almost identical in size and mass and are relatively close in their distance from the Sun.

But in reality, the worlds could not be more different.

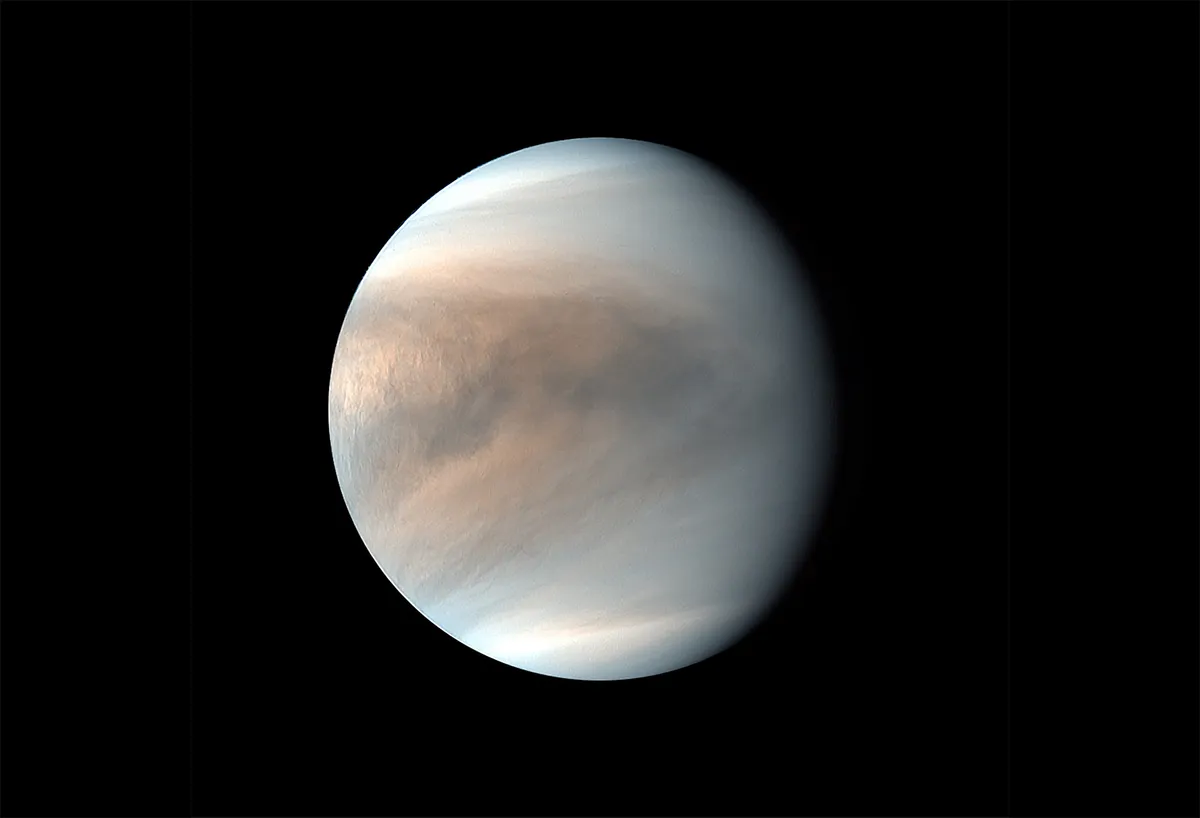

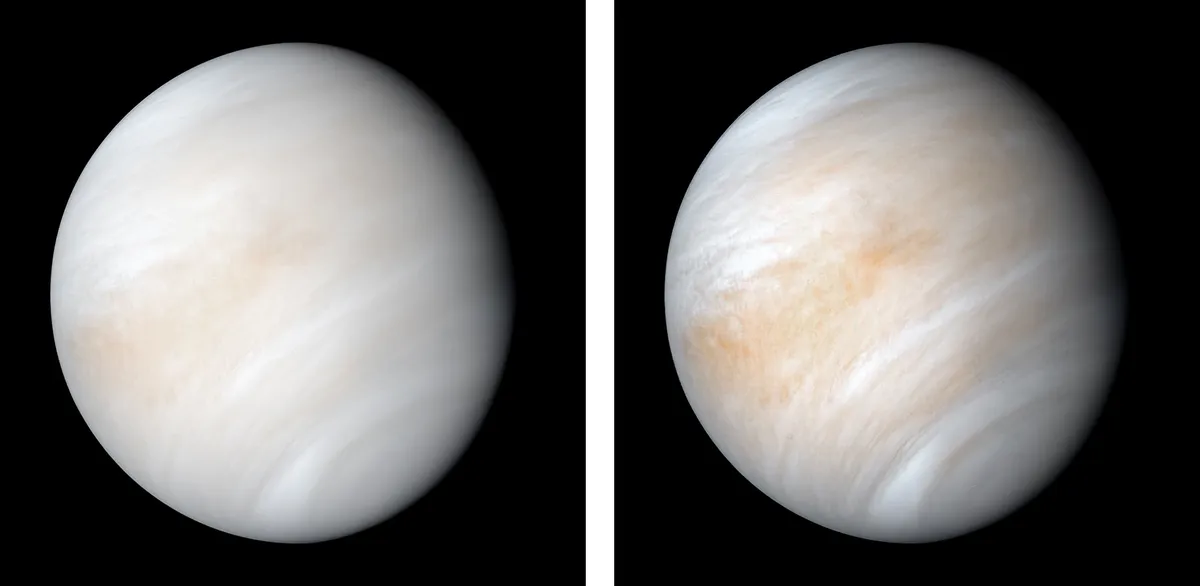

Not only is there the fact that Venus spins backwards, butV enus is also shrouded from view by thick clouds of sulphuric acid, which float in an atmosphere so dense the surface pressure is 92 times what it is on Earth: about the same as 1km underwater.

Temperatures on Venus are hot enough to melt lead, as the planet is in the grip of a runaway greenhouse effect.

Venus was once highly volcanic, and this pumped out vast amounts of carbon dioxide.

On Earth, plate tectonics recycle the carbon from eruptions back into the rock, but Venus doesn’t have any tectonics.

Instead, carbon dioxide levels rose until it made up 95% of the atmosphere. This acts like an insulating blanket, trapping the Sun’s heat.

As the temperature rose, what water there was on Venus evaporated, forming a thick layer of swirling cloud that trapped even more heat, contributing to the creation of the planet's inhospitable conditions.

Recently, astronomers have managed to detect signs of phosphine on Venus, which could be evidence of microbial life in the planet's clouds.

Venus quick facts

- Diameter: 12,104km (0.95 times Earth)

- Mass: 4870 billion trillion kg (0.81 times Earth)

- Distance from the Sun: 108 million km (0.72 AU)

- Length of day: 117 days

- Length of year: 225 days

- Number of moons: 0

- Average temperature: 464ºC

- No of spacecraft visitors: 24

- Type of planet: Rocky

Here are 49 facts about Venus, our poisonous, hell-like neighbour!

Venus is referred to as Earth’s twin

Earth and Venus are, indeed, ostensibly quite similar. Not only is Venus’s orbit the closest to Earth’s of all the Solar System planets, its radius is 0.95 times that of Earth, and it also has 90% of Earth’s surface area, 85.7% of Earth’s volume, 81.5% of Earth’s mass and 90% of Earth’s gravity. But that’s where the similarities end.

The average surface temperature is 464°C (867°C)

Temperatures at ground level can range from 438°C to 482°C (820-900°F). The reason it’s so hot, is that at some point in its history, Venus has experienced runaway global warming. And that’s because…

Its atmosphere is mostly carbon dioxide

The atmosphere on Venus is 96.5% carbon dioxide and 3.5% nitrogen, with very small traces of other gases (including sulphur dioxide). It’s also 50 times denser than Earth’s, and atmospheric pressure is 92 times that of Earth.

It's gases aren't what you'd expect

At surface level, Venus’s carbon dioxide and nitrogen aren’t in gaseous form. Instead, they’re present as supercritical fluids, a state of matter that shares properties with both liquids and gases but can properly be classified as neither. This is a result of the region’s super-high pressure and temperature.

Venus may once have harboured life

Once upon a time, a pre-warming Venus probably had a similar climate to Earth, and may even have had a similar ecosystem. But these days, it’s so hot that were you to step foot on the planet, your blood would boil instantly… which pretty much rules out the presence of life as we understand. It.

We don’t know much about its internal structure

Venus is believed to have a core, mantle and crust, like the other rocky planets, but that’s about as much as scientists have so far been able to determine. What we do know is that it has no internal dynamo, and so has only a weak magnetic field.

Plate tectonics aren’t really a Venusian thing

There is no evidence for plate tectonics on Venus. On Earth, some regions of Earth’s crust are slowly being subducted back down into the mantle, while in other regions new crust is emerging from it, which is why continents move over time. That doesn’t happen on Venus – possibly because its mantle is more viscous and slower-moving than Earth’s.

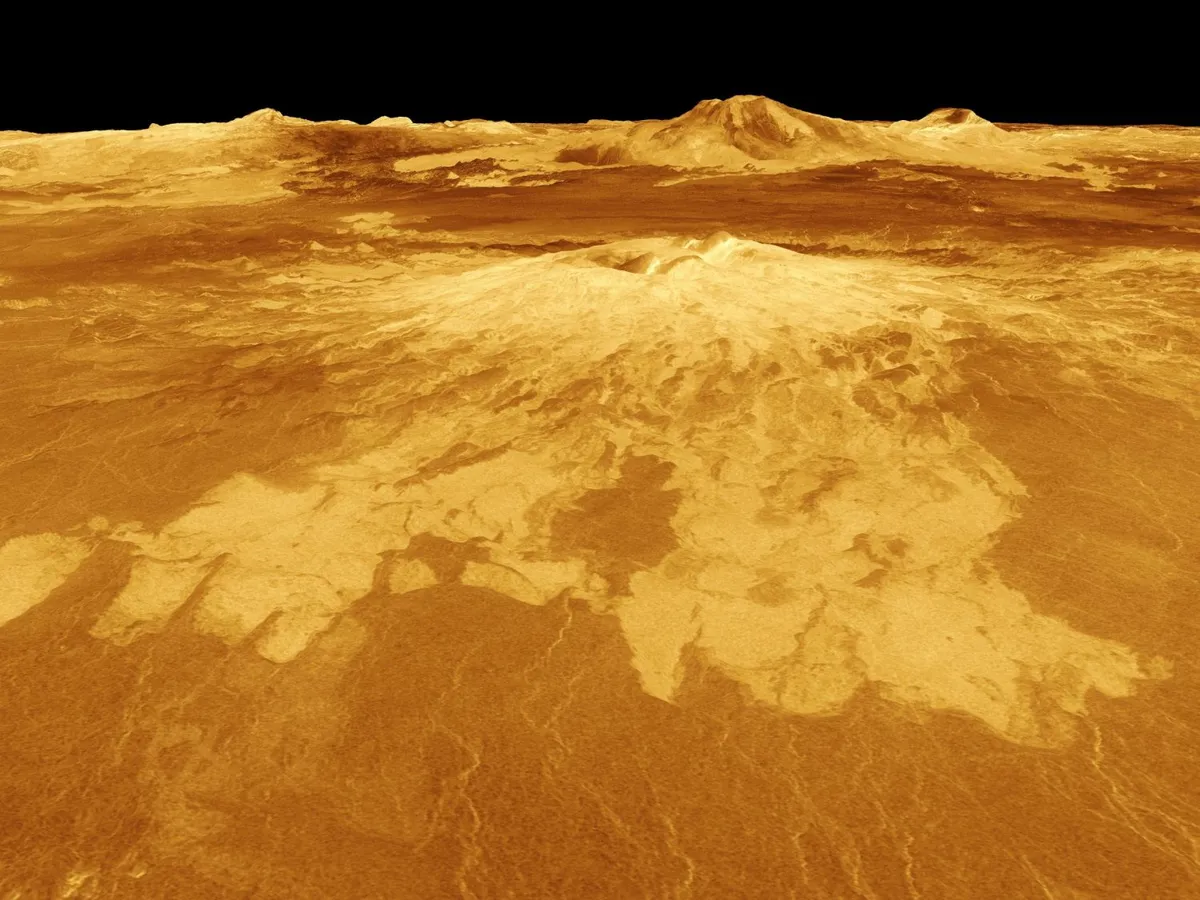

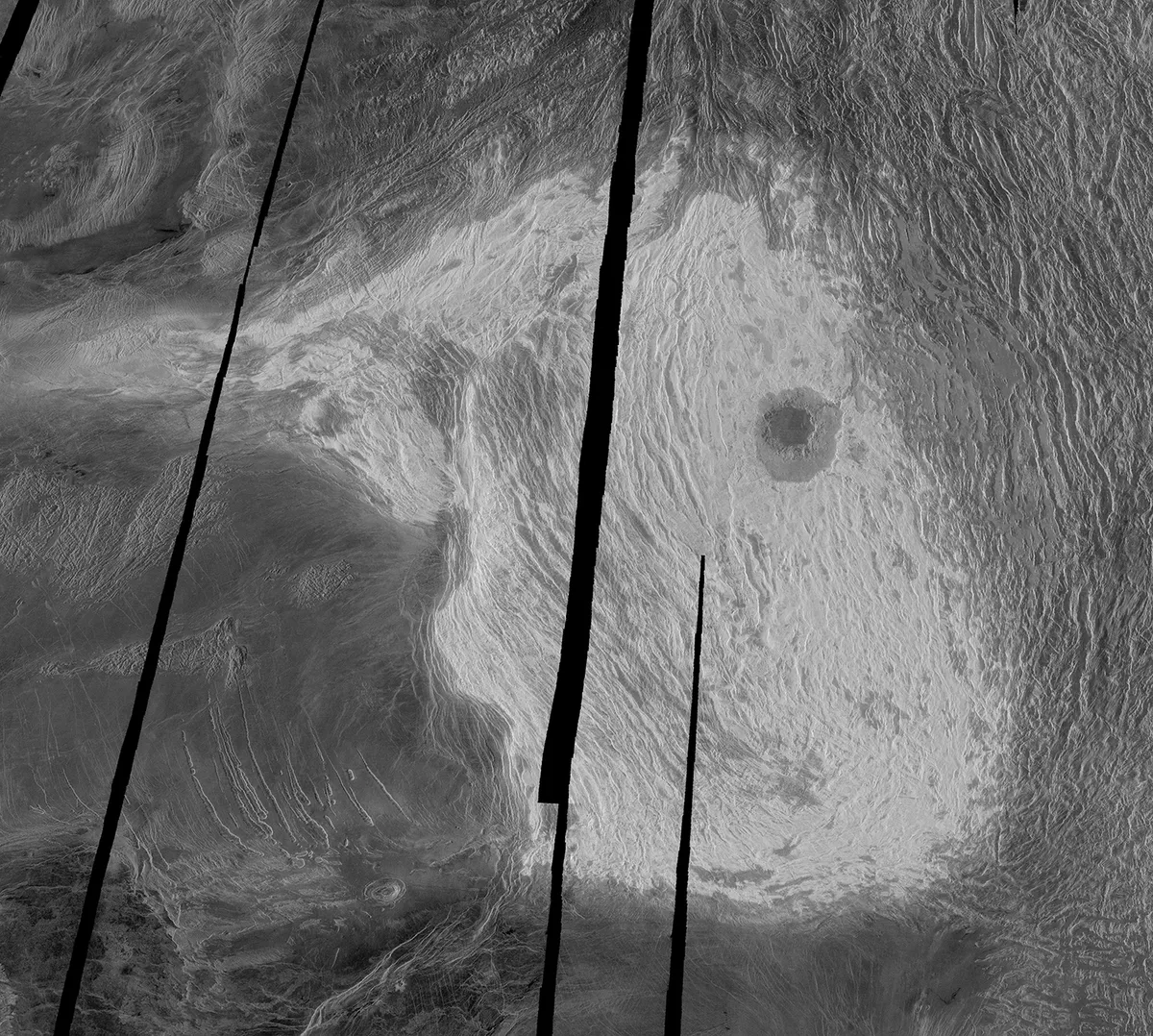

Venus has volcanoes

Venus might not have plate tectonics, but it has volcanoes. Oh boy, does it have volcanoes! Over 85,000 have been identified, and there’s good evidence that at least some of those are still active. What’s more, 167 of those measure more than 100km (62mi) across, whereas Earth has just one volcano of that size – Hawai’i or Big island, the largest of the islands making up the US state of Hawaii

Volcanism has shaped its topology

With no plate tectonics, it’s lava flows that have been the biggest influence on Venus’s physical geography. Accordingly, the planet’s surface is mainly smooth and flat – the kind of landscape you get when surface lava flows cool and solidify. It does, however, have three continents (areas of raised ground) – one in its northern hemisphere and two in its southern hemisphere.

Its northern continent is called Ishtar Terra

Ishtar Terra is somewhere between Australia and the US mainland in size, and is named after the Babylonian goddess of war, love and fertility. In this region can be found the planet’s four mountain ranges, the largest of which is called Maxwell Montes.

In the southern hemisphere you’ll find Aphrodite Terra and Lada Terra

These regions are named after the Greek and Slavic goddesses of love, respectively. Aphrodite Terra is the largest of the three Venusian continents and is located near the equator, while Lada Terra is the smallest and lies close to the planet’s southern pole.

Venus's motion is retrograde

To put that more simply, Venus spins 'the wrong way round'. All eight of the Solar System planets orbit the Sun in an anticlockwise direction, and most of them rotate on their axis counterclockwise as well – only Venus and Uranus have an anticlockwise orbit but rotate clockwise.

On Venus, the Sun rises in the west and sets in the east

That’s the opposite way round from Earth, which is unsurprising given that the planet’s spinning in the opposite direction! However, were you somehow able to stand on the Venusian surface (which you can’t), you’d likely rarely or never actually see the Sun, anyway – thanks to the dense clouds in its upper atmosphere.

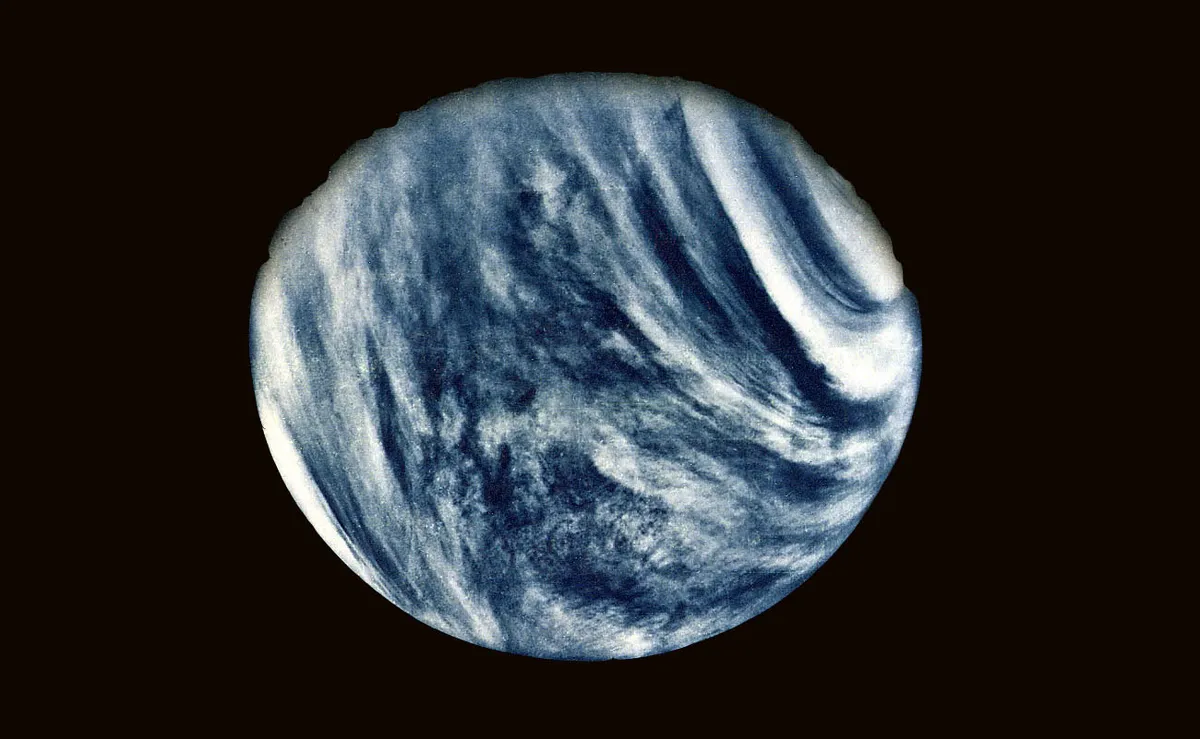

Venus has unbelievably dense clouds

This is one reason we don’t know as much about Venus as we do about the other planets – it’s hard to get a good view because of the thick cloud cover. Oh, and did we mention that those clouds are made of sulphuric acid? Well, we have now!

Venus's clouds could harbour life

While the surface of Venus is pretty much a deadly hellhole, things get more pleasant a few kilometres up. In fact, at an altitude of around 50km (30mi) above the surface, the temperature and atmospheric pressure are similar to those found on Earth. You’ve still got all that CO2 and sulphuric acid to contend with, but it’s possible there could be extremophile microorganisms there.

Its upper atmosphere may or may not contain phosphine

In September 2020, a team led by Cardiff University astronomer Jane Greaves detected the presence of phosphine (a compound of phosphorous and hydrogen) in Venus’s upper atmosphere. On Earth, phosphine is associated with anaerobic processes – biological processes that require no oxygen – and so the chemical is considered a useful ‘biosignature’, an indicator that could reveal the presence of life on oxygen-free planets.

Venus has few impact craters

All planets and satellites are subject to impacts by comets and asteroids from time to time, but on Venus there are far fewer craters than we see on other planets. It’s believed that volcanism has smoothed over most of them; this suggests also that Venus’s current surface is quite ‘young’, in geological terms (current estimates put the age of the surface at around 150 million years, whereas the planet itself is around 4.5 billion years old).

Those it does have are large – and immaculate

Impact craters elsewhere in the Solar System tend to be quite raggedy affairs and come in all different sizes. The 1,000 or so known on Venus all look as though they could have formed yesterday, and none are less than 3km (1.9mi) across.

Their pristine appearance can be explained by the relative youth of Venus’s surface (the craters simply haven’t had long to erode), while the size issue is explained by Venus’s unusual atmosphere – it’s so dense that any incoming bodies smaller than 50m (165ft) across simply burn up on entry, and hence only larger objects ever reach the ground.

It has distinctive surface features

Geological features that are unique to Venus include flat-topped volcanoes called ‘farra’ (or sometimes ‘pancakes’), radial fractures called ‘novae’, spiderweb-like patterns known as ‘arachnoids’ and concentric rings of fractures called ‘coronae’. All of these result from volcanic activity.

It’s the third-brightest object in Earth’s sky

By day – and Venus is quite often a naked-eye object, even in daylight – only the Sun and the Moon are brighter. Once the Sun’s gone to bed then the Moon rules supreme and Venus moves up into the silver medal position.

Venus can be a morning or evening object

Venus is sometimes visible in the mornings, just before sunrise, while at other times it’s visible in the evening, just after sundown. That's why Venus is known as the Morning Star or the Evening Star. As a result, it was for a long time believed to be not one object but two, with different cultures coming to the realisation that those two objects were the same thing at different times. The ancient Sumerians, for instance, knew it was one object, and their civilisation collapsed around 1800 BC. The ancient Eyptians, on the other hand, may not have worked that out until around 600 BC.

Venus has no moons

Venus has no natural satellites but it does have one ‘quasi-satellite’ in the form of an asteroid called Zoozve. A quasi-satellite orbits the Sun rather than any planet, but has an orbital trajectory that keeps it close to a given planet (in this case, Venus) at all times. Zoozve was discovered by astronomer Brian Skiff at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, USA on 11 November 2002, and estimates of its size range from 200m to 500m (660-1,640ft) across.

Its days and years are a bit odd

On Earth, a day is 24 hours… or more accurately, a solar day is 24 hours while a sidereal day is 23h 56’. A solar day is the time between the Sun being directly overhead one day and being directly overhead the next: a sidereal day is the time Earth actually takes to rotate once upon its axis (the difference is due to Earth’s orbiting the Sun as well as spinning on its axis).

The situation on Venus is more complicated, though, thanks to its slow, retrograde rotation. A solar day on Venus lasts for 116 days and 18 hours, but a sidereal days lasts for 243 days – that’s actually longer than a Venusian year, which lasts for just 224.7 days.

Venus has phases, like the Moon

Seen through a telescope from Earth, Venus may appear as a full circle, or in any of the several phases exhibited by our own Moon (as a thin crescent or a semi-circle, for instance). Mercury is the only other planet to exhibit phases, as seen from Earth, and it's because they're both inner planets, orbiting between Earth and the Sun.

It was observed through a telescope by Galileo

Galileo first spotted Venus with a telescope in December 1610, and published his observations regarding its phases in his 1613 pamphlet ‘Letters on Sunspots’.

Venus helped sound the death knell for geocentrism

The phases observed by Galileo make perfect sense if all the planets orbit the Sun, as we now know to be the case. They wouldn’t make any sense if the planets and the Sun orbited the Earth, as people used to believe. Galileo’s observations of Jupiter were therefore crucial in establishing our modern, heliocentric understanding of the Solar System.

It has no seasons to speak of

Earth’s seasonality is due to our planet’s axial tilt. Earth sits at an angle of 23° relative to its axis, so at different times of the year, a given point on its surface can be closer to or further from the Sun. The axial tilt of Venus is just 3°, which isn’t enough to cause seasonal fluctuations in temperature.

Temperatures on Venus don’t vary much

Not only does the temperature not change much over the course of a year, it’s also not significantly colder on the side facing away from the Sun (ie, at night) than on the side facing towards it (ie, by day). Nor is notably any warmer at the Poles than it is at the equator. This means that Venus is effectively ‘isothermal’ – one temperature everywhere, all the time. What fluctuations are detected can largely be ascribed to altitude.

Venus has no rings

None of the Solar System’s small, rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars) have rings, whereas all of its gas and ice giants (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) do. Venus does, however, have a dust ring cloud: this is effectively a large, super-faint ring consisting of very fine particles of dust. Mercury has one of these, too.

The origin of its dust ring cloud is uncertain

The faint band of material seen around Venus may be leftover material from the formation of the Solar System, or it may be material left behind by Venus-orbiting asteroids – we still don’t know.

It’s the closest planet to Earth (but only sometimes)

At perigee (the point when the two planets’ orbits bring them closest together in space), Venus comes closer to Earth than any other planet. However, Venus’s orbit means that most of the time, Mercury is actually closer to Earth than our presumed neighbour. Remember that – it’s one of those facts you must might win a pub quiz with!

It’s sometimes blocked from view by the Moon

Lunar occultations – when the Moon passes blocks out a more distant celestial body, as seen from Earth – often occur, blocking our few of Venus temporarily.

Venus transits of the Sun are much rarer

Although looking at a picure of the Solar System might lead you to expect Venus to pass between Earth and the Sun quite regularly, the interplay of the two planets’ orbits, rotational periods and so on means you’ll very rarely see the planet pass across the Sun’s surface. In fact, only eight such transits have ever been observed! When they do happen, they happen in pairs – the next is due to happen in December 2117, then December 2125.

There’s some kind of ‘snow’ on its mountaintops

Observations by the Magellan spacecraft in 1995 revealed patches of a bright, reflective material atop Venus’s highest peaks. This is believed to have precipitated out of the atmosphere at high altitudes (ie, at low pressures), just as water ice (snow) does on Earth, but its chemical constitution is uncertain – though tellurium (a white metallic element) and lead sulphide are among the leading candidates.

Venus's CO2-rich atmosphere results from its weak magnetosphere

Without much of a magnetic field to hold them close to the planet, lighter molecules such as hydrogen, helium and oxygen in Venus’s atmosphere are very susceptible to the solar wind, and so are blown away into space – thus explaining both the carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere that’s left behind, and the absence of water on the planet.

The planet may or may not experience lightning

There is some evidence, mostly derived from observations by the Soviet Union’s Venera probes, for lightning in Venus’s upper atmosphere. But the results haven’t proved consistent, so we can’t say for sure if there is lightning present there or not. If there is, it’s likely to be volcanic in origin, caused by a build-up of static electricity as ash and dust particles collide within volcanic plumes.

Daytime appearances were once considered a good omen

People used to believe that Venus became visible during momentous events – for instance, it was visible with the naked eye during daylight hours on the day that Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as President of the United States.

It’s named for the Roman goddess of love

Venus was the Roman goddess of love, but Venus’s association with romance and the feminine goes back a lot further than that. Venus was the Romans’ name for the Ancient Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite, and Aphrodite in turn was based upon the earlier Sumerian goddess Inanna, or Ishtar – and both were also associated with the planet. Hence why Venus’s two largest continents are called Ishtar Terra and Aphrodite Terra.

In Far Eastern cultures, Venus is often associated with metal

Many East Asian cultures traditionally believed in five elements – fire, water, earth, wood and metal. Venus was associated with the latter – hence it is known in Chinese as “Jīn-xīng (金星)” (the golden planet), while in Japan and Korea it is known as “the gold star”.

Its symbol is also the symbol for womanhood

The Venus symbol, which looks like a circle with a cross coming out of the bottom, is also a symbol widely used to denote all things female or feminine – just as the Mars symbol (a circle with an arrow emerging top-right) is used to denote for all things male or masculine. This symbol is sometimes also known as the ‘Venus mirror’, because Venus was associated with copper, and copper was used to make mirrors.

Most of its surface features are named after women

The exceptions are the planet’s highest mountain (Maxwell Montes, named after Scottish physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell) and a few other high peaks that were observed and named prior to the International Astronomical Union decreeing that Venusian surface features should take the names of female figures from history or mythology.

Early attempts to visit Venus failed

Early attempts at exploring our near-neighbour were beset by difficulties, with the first two probes (both Soviet in origin) both failing – Sputnik 7, AKA Tyazhely Sputnik, launched in February 1961 but never got beyond Earth orbit, while Venera 1, which launched later that month, did reach the planet, but by that time its communications systems had failed.

Mariner 2 was the first spacecraft to visit Venus successfully

NASA’s Mariner 2 craft launched on 27 August 1962 and by the December of that year had completed a flyby of Venus at an altitude of 34,773 km (21,607 mi), and sent back measurements of the planet’s temperature and magnetic field, as well as measuring the local strength of the solar wind.

The first humanmade craft to land on Venus was Venera 3

Russia’s Venera 3, launched in November 1965, reached Venus in March 1966 and crashed into the planet’s surface, but again, a communications failure meant this mission sent back no useful data. It wouldn’t be until 1970 that Venera 7 was able to effect a soft landing on the planet and send back a limited amount of data – though in the meantime there had been several successful flybys by other craft, notably the US Mariner 5 and Russian Venera 4, 5 and 6 probes.

Mariner 10 became the first craft to send back images in 1974

By 1974, 12 craft had successfully reached Venus and eight had managed to return at least a limited amount of data to Earth, but that didn’t include pictures. Then, on 5 February 1974, Mariner 10 flew within 5,768km (3,584 mi) of the Venusian surface and sent back the first images – despite the craft’s primary mission being to visit Mercury. It had gone by way of Venus in order to conduct a ‘gravity assist’ flyby – the first time such a manoeuvre was successfully achieved.

NASA once had a Venus mission called ‘HAVOC’

One of the most interesting Venus missions was undoubtedly NASA’s HAVOC programe – the High-Altitude Venus Operational Concept, a project that ran from 2014 to 2017. Theoretically, HAVOC was exploring the possibility of Venus’s upper clouds sustaining some kind of life – though no spacecraft were ever launched as a result, and on cancelling funding in 2017, NASA claimed that it had only ever been a hypothetical exercise designed to enhance would-be space engineers’ analytical skills

Several nations are currently planning missions to Venus

NASA is planning for two upcoming Venus missions, called DAVINCI and VERITAS. The former will mostly be studying the planet’s atmosphere, while the latter is a mission to map the planet’s surface more accurately. India and the United Arab Emirates also have Venus missions in the pipeline, as does ESA – though the next mission actually to launch, if all goes according to plan, will the Venus Life Finder, a private space mission being conducted jointly by MIT and RocketLab (a rival to SpaceX).

It sometimes shows a ‘green flash’ in photos

Light becomes dispersed as it passes through Earth’s atmosphere, but different wavelengths are dispersed to a greater or lesser extent – with the result that seen from certain angles, bright objects like planets and stars can appear to ‘glow’ blue at the top and red at the bottom. If this blue light is then further scattered by atmospheric conditions, the next colour in the spectrum (green) can become dominant.

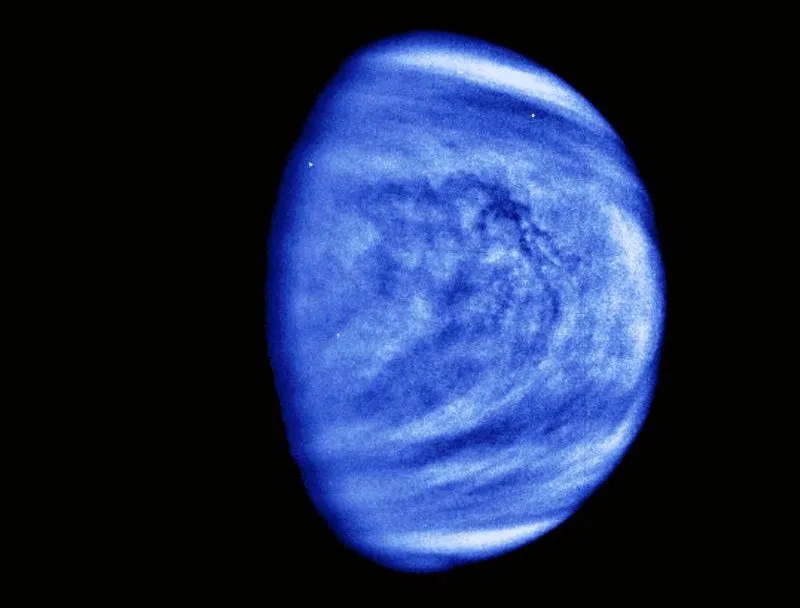

There are streaks in its upper atmosphere

Images of Venus captured in ultraviolet light reveal mysterious streaks in the upper atmosphere. It’s been suggested that these could be evidence of microbial life in the region – an idea first proposed by Carl Sagan in 1963 – though others have posited the presence of iron-rich minerals as a more likely alternative explanation.

What are your favourite Venus facts? Let us know by emailing contactus@skyatnightmagazine.com