Back in September 2008, Absolutely Fabulous star Joanna Lumley took BBC viewers on a journey to witness the Northern Lights. Lumley had been fascinated by the aurora for decades and longed to see it, finally embarking on her own expedition to the hyperborean extremes of Norway.

The documentary, Joanna Lumley in the Land of the Northern Lights, delivered on its promise with an emotional climax, complemented by beautiful time-lapse photography that lingered in the minds of many would-be aurora chasers.

In my years of accompanying Brits to northern climes to see the Lights, I’ve heard many accounts of watching that documentary, the most memorable aspect being Lumley’s own touching reaction.

Read more:

- What do aurorae look like on other planets?

- How to find the aurora by yourself

- How to detect the aurora with a magnetometer

- Should you go on an aurora cruise?

After long anticipation, those people have then encountered the Lights themselves, their reactions a perfect reflection of the one that had motivated them.

There’s something universal about the awe we feel in the presence of such a strange and wonderful encounter. My first sight of a dynamic auroral display high overhead was so spellbinding that I unthinkingly walked forward in awe, stepping onto a frozen stream and plunging one foot through the ice.

Needless to say, that brought me back to Earth swiftly! But soon I was entirely enthralled by the sky again, the cold merely a background sensation unable to break my attention. It is a truly arresting phenomenon that is entirely unlike anything else you will ever see.

Darren Flinders, Retford, Nottinghamshire, 10 May 2024

Equipment: Sony a7 III camera, Samyang 14mm lens

A history of observing the Northern Lights

It’s not surprising that the internet’s largest tracker of ‘bucket list’ suggestions ranks seeing the Northern Lights at the number one spot, and by a wide margin.

Word gets around, and those who have been fortunate enough to witness a striking display are at once both excited to tell their friends and unable to find sufficient language to do it justice. "You just have to see it for yourself".

Richard Clibborn, Ardoe, Aberdeenshire, 10 May 2024

Equipment: iPhone Pro 15 Max

Of course, not everyone needs to travel to see the Northern Lights regularly. For a few million people in northerly parts of the globe they’re a familiar, nightly occurrence between autumn and spring.

There is no exact record of their discovery – the earliest Arctic settlements date back over 1,000 years – but there are notable mentions of historic sightings in regions where they seldom appear; for example, ancient Greece and China.This is only possible under exceptional circumstances, perhaps only once on a timescale of many generations.

The sight of the aurora must have been inexplicable for early witnesses and hard to believe, if not sheer legend, for those they tried to explain it to.

Galileo, who investigated reports with great interest, proposed that they were formed by sunlight reflected from the atmosphere. In 1619, he coined the term ‘aurora borealis’, from Latin: ‘Dawn of the North’.

In fact, ‘Northern Lights’ is actually the much older name. In the ancient Icelandic language they are called ‘Norðurljós’ – literally ‘North Lights’.

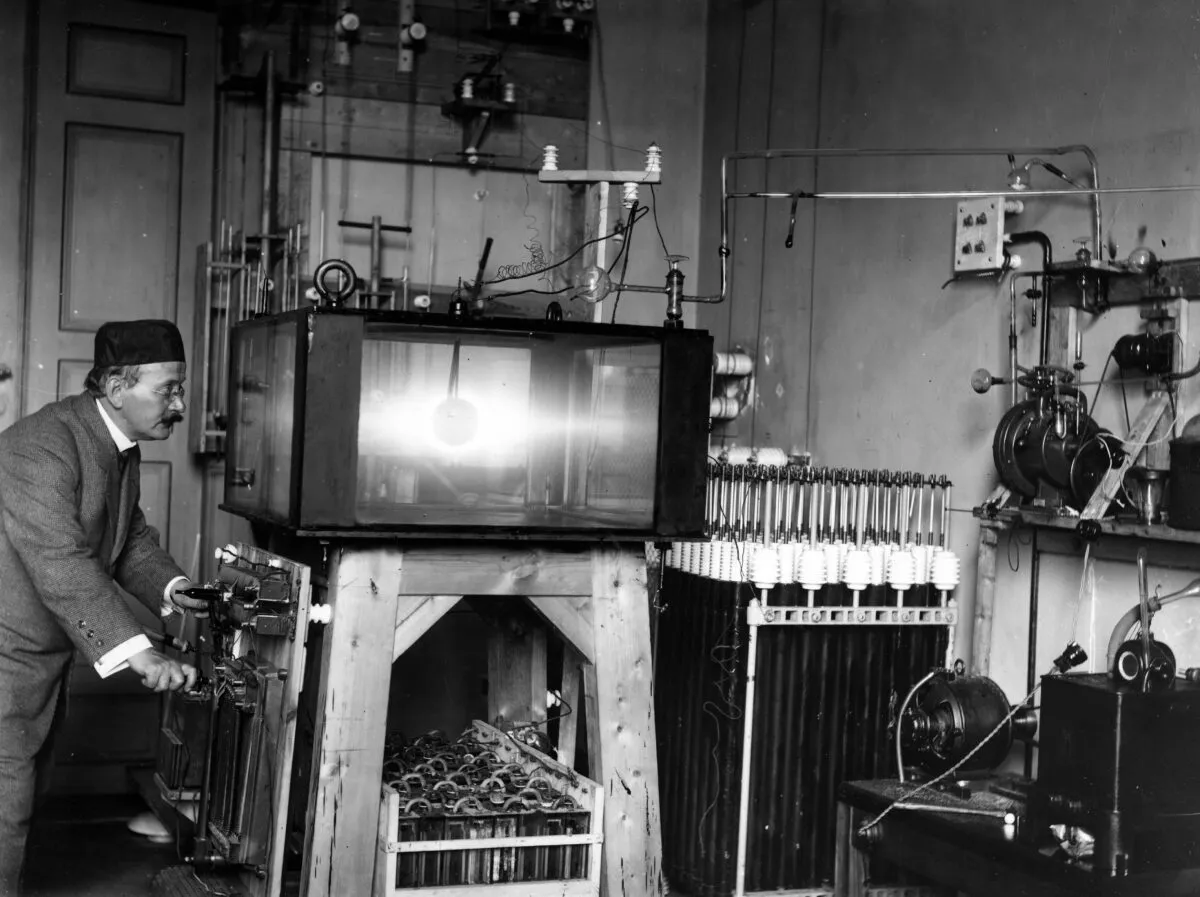

The first serious scientific proposal for their origin did not arrive until as recently as the end of the 19th century, when Norwegian physicist Kristian Birkeland replicated them in the laboratory.

Using a magnetised sphere to represent Earth, he demonstrated that glowing ovals appear around the magnetic poles when gas is excited by high energy electrons.

What causes the aurora?

Nowadays, there's no secret to what causes the Northern Lights. The aurorae are a continuous reminder of our planet’s unbroken connection with its parent star.

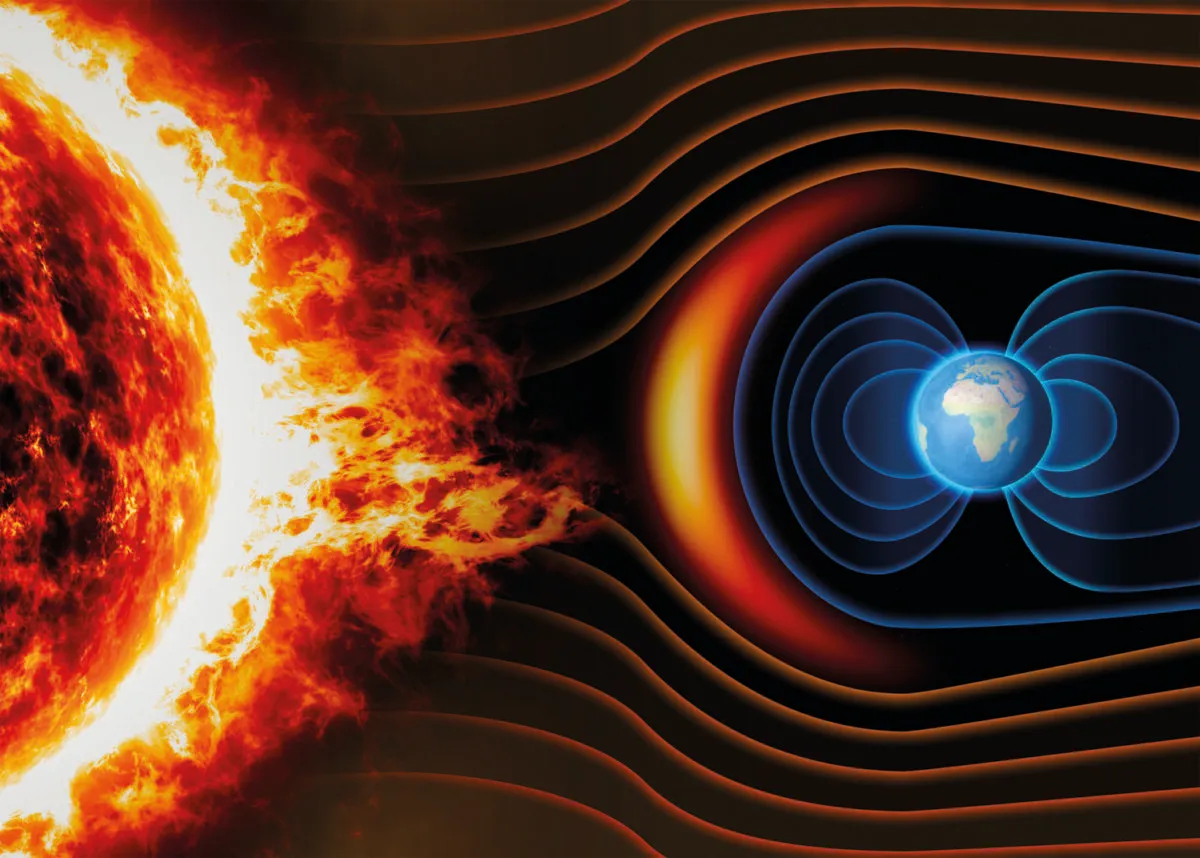

What we tend to imagine as empty space in the Solar System is actually flooded with solar radiation: protons and electrons streaming away from the Sun’s atmosphere at an average speed of 1.6 million kilometres per hour.

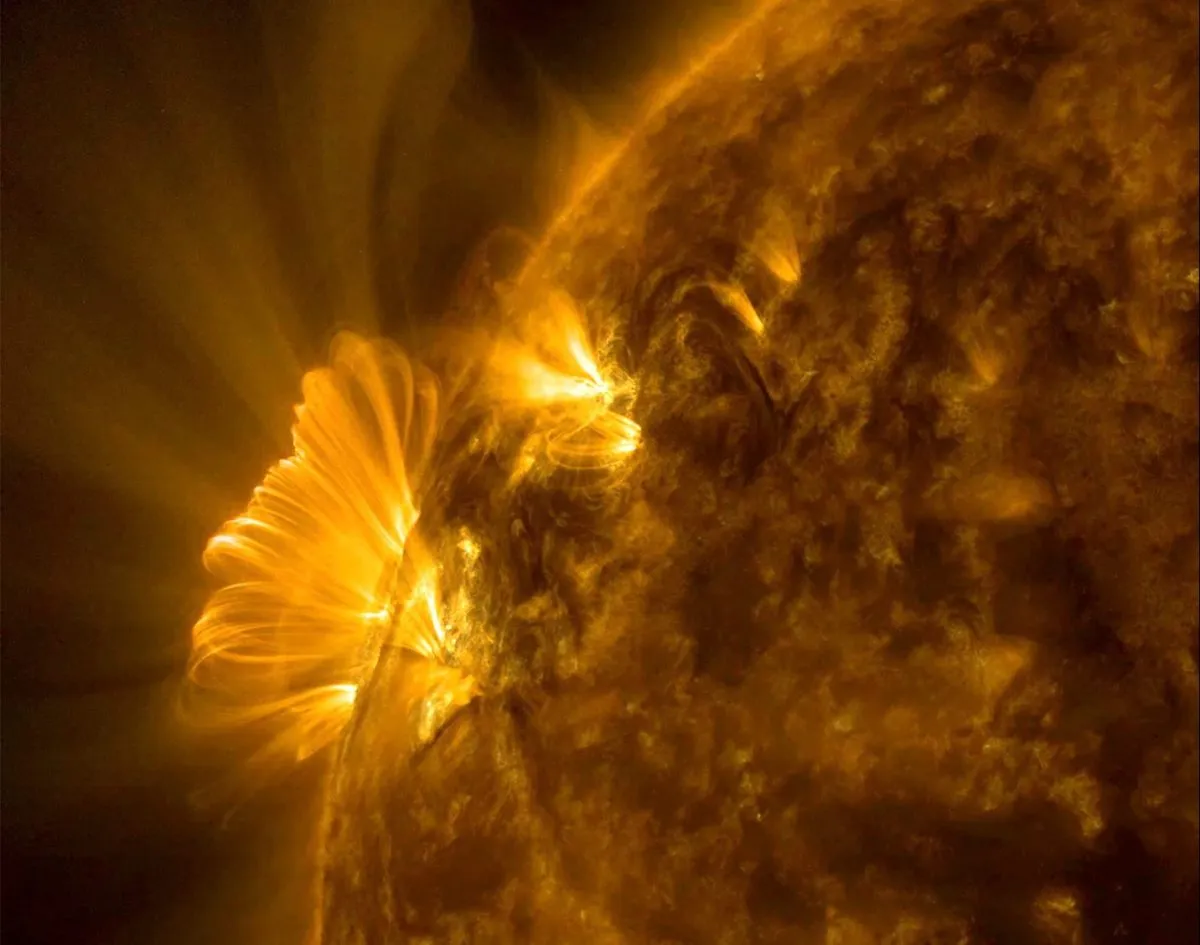

Enormous, high-energy events such as coronal mass ejections (CMEs) also release colossal quantities of solar plasma and magnetic energy into the planetary region.

Far from being smooth in distribution, the solar wind is lumpy, its influence on Earth ever-changing.

The study of space weather enables us to forecast the cause of the Northern Lights, as solar wind particles are captured by Earth’s magnetic field and accelerated towards the magnetic poles.

Diving into the atmosphere, they strike gas atoms and molecules, ionising them and resulting in the release of different colours of light.Radio waves are also released and, under specific conditions, a crackling sound may be produced.

The strength and motion of the Northern Lights varies sensitively with both the intensity of the solar wind and the stability of Earth’s magnetic environment.

When a pocket of solar magnetic energy, released during a CME, strikes Earth, a geomagnetic storm occurs, expanding the size of the auroral ovals and bringing the Northern Lights further south.

At such times, they can cover the sky as seen in the Arctic and break clear from the horizon for observers in Scotland, becoming visible across much of the northern UK.

Why are there different colours of the Northern Lights?

The most prominent colour of the aurora is green, released by excited oxygen atoms between 100–150km above ground. Our eyes are sensitive to this colour, even in low light.

Dynamic displays of rippling, dancing curtains often have a pinkish edge at the bottom and for fleeting moments, the colour can be very prominent against the green above it.

The pink colour of the aurora results from a mix of blue and red light emitted by molecular nitrogen at lower altitudes.

Cameras, without the colour bias of the dark-adapted eye, can draw out an extraordinary range of hues from a bright display. For more on this, read our guide on how to photograph the aurora.

At high altitudes, atomic oxygen creates a deep red, almost crimson fade from the top of an auroral curtain to stars above it. The mixing of colour can also result in yellows and blues appearing with varying degrees of clarity.

Meanwhile, the curtains may hang stoically, or dance playfully. Sometimes they divide or merge in line with the ‘sheets’ in Earth’s magnetic field.

During an intense display you may be lucky and find yourself looking straight up into an auroral corona at the zenith, making it appear as though it is enveloping you.

John Chumack, Fairbanks, Alaska, USA, 12 March 2024

Equipment: Canon EOS 6D camera, 16mm lens, Bogen tripod

Canon 6D, 16mm lens, ISO 3200, 10 second exp.

When is the best time to see the Northern Lights?

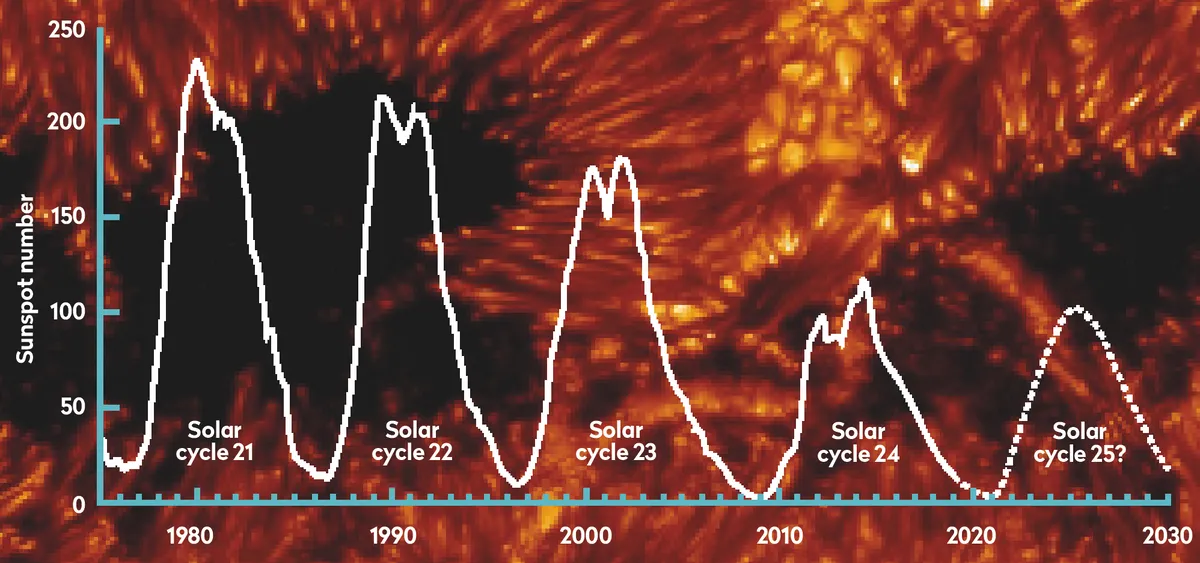

There is a common misconception that the aurorae are only visible at a peak of the solar cycle, which occurs once every 11 years.

Given that we're currently in Solar Cycle 25 and maximum solar activity is forecast for 2025, this would mean waiting quite some time.

Fortunately, this isn’t necessary. While increased solar activity does indeed provide more opportunities for explosive auroral displays, they can still be seen in quieter years with reasonable frequency.

Mid-September and October are particularly good times to make your first expedition to see the aurora. Between November and January, the extreme cold of northern nights can be a real challenge.

February and March are a little kinder and typically less expensive months to travel. During the northern summer months, many places at high northern latitudes experience short hours of night, or no real night at all, so the sky does not get sufficiently dark enough for the Northern Lights to become visible.

Can you see the aurora from the UK?

Many excellent aurora-chasing destinations are within reach of the UK: Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Finland are all famed for their access to the Northern Lights on solid ground, while cruises and short flights can take you up to the Arctic Circle on a dedicated trip.

Read more about astrophotography in Finland

But it is possible to see the aurora from the UK. Consider an aurora-chasing trip to Inverness. I spent some of my childhood near Lossiemouth, where the Lights can be glimpsed over the North Sea.

On rare occasions, they can be seen as far south as North Wales, giving millions of Britons the opportunity to experience the phenomenon without needing to travel too far.

Successful aurora-chasing is a matter of picking the right time and place, but luck will always play a part, just as with any other form of astronomy.

However, no matter the conditions, your first view of this magnificent natural wonder will always stay with you. Neither freezing cold nor partial cloud can spoil it.

Almost everyone I’ve introduced to the Northern Lights initially expected to relive Joanna Lumley’s televised experience, but she was luckier than most get.

However, what they eventually saw was infinitely better: the real thing. It’s worth the adventure!

Can't travel to the aurora? Click here to learn how to see them online

9 top tips for spotting the Northern Lights

- Make a decision on your aurora-chasing destination and stick with it. Travel close to new Moon and prepare to go looking every night during your trip, even if the forecast is cloudy.

- Use local weather services to choose a location with the highest chance of clear sky throughout the night.

- Research your viewing site and be prepared to spend some hours there. You should aim to stay out until at least 01:00 to 02:00

- Find a spot away from a road to avoid interference from vehicle headlights.

- Take care driving on unfamiliar terrain, particularly in the Arctic wilderness! If renting a car, consider something suitable for rough roads.

- You don’t need any equipment, but if you’re planning to photograph the aurora, set up your camera before stepping into the cold. Turn off your car’s headlights and any interior lights.

- If it’s windy, park your car in such a way that you can use it as a windbreak while keeping a clear view of the north.

- Scan the northern horizon. Look for diffuse, cloud-like patches of light. Most displays are gentle to begin with. The luminosity and faint green colour of a brightening auroral display are very distinct.

- Keep watching until the display picks up in energy. You’ll see more movement and colour as auroral curtains ripple across the sky. Use a wide aperture and take exposures of a few seconds with your camera to capture the colours.

Tom Kerss is an astronomer, science communicator and author of The Northern Lights: The Definitive Guide to Auroras. Listen to his monthly stargazing podcast at starsigns.live.