In 1919 two astronomers set out on an expedition to prove Einstein's new general theory of relativity by observing a total solar eclipse. The Observatory Science Centre at Herstmonceux is marking its involvement with this historic astronomical endeavour with a series of events celebrating one of the turning points in our understanding of the Universe.

The Observatory Science Centre at Herstmonceux is marking the 100th anniversary of the total solar eclipse that helped to support Einstein's general theory of relativity.

One of the historic observatory's working telescopes was used to photograph the eclipse on 29 May 1919, while one of the lenses of the observatory's 13-inch astrographic refractor was taken to Sobral in Brazil to help astronomers Frank Dyson and Arthur Eddington observe the bending of starlight around the Sun, providing evidence for Einstein's theory.

From 25 May to 2 June 2019, the Observatory Science Centre will host tours of the dome housing the 13-inch refractor along with solar observing sessions, demonstrations of the theory of general relativity, plus other workshops and activities.

On the day of the anniversary, Dr Stephen Wilkins from the University of Sussex and Graham Dolan from the Royal Observatory Greenwich will be joining the Herstmonceux team to celebrate the historic astronomic event.

Find out when the next eclipse is happening.

How did an eclipse help prove Einstein's theory?

Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity, published in 1916, is considered one of the greatest achievements of modern physics.

It changed the view of gravity as a force of attraction between two objects.

Instead, Einstein argued, there was no such force. Gravity was an effect of the warping of space and time caused by matter.

Many will be familiar with the simple experiment that demonstrates this concept, using a blanket of material and marbles: stretch the blanket out, place a weight in the middle and the blanket droops accordingly.

Roll marbles at an angle onto the blanket and they will spiral inwards.

In this experiment, the blanket represents spacetime, the weight represents mass, and the marbles represent objects feeling the 'gravitational pull' caused by the mass warping spacetime.

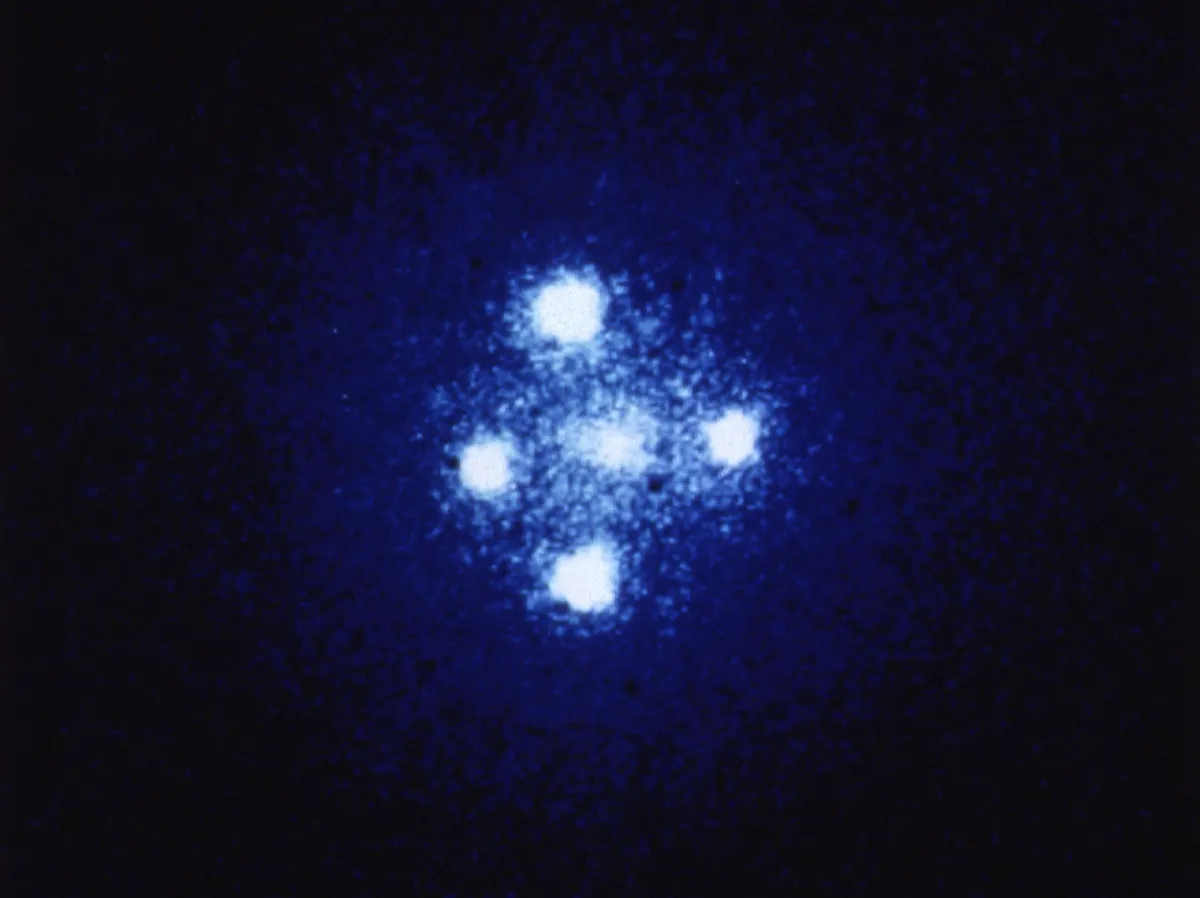

In recent years the theory has been proven in the detection of gravitational waves caused by collisions between colossal objects like black holes, or through observing a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing, in which light from a distant object like a pulsar or galaxy is bent and magnified by a closer massive object like a galaxy cluster.

While Einstein's theory generated much debate upon its release, many astronomers of the early 20th century were keen to test the theory out.

One such advocate was Frank Dyson, the British Astronomer Royal at the time.

He predicted it should be possible to measure whether starlight was bent around the mass of the Sun during a solar eclipse.

The upcoming 1919 solar eclipse would be the perfect opportunity, as the Sun would be situated in the rich star field of the Hyades.

They would, he reasoned, be able to view the effects of Einstein's theory on starlight.

Two expeditions were organised to view the eclipse of 1919: one to Sobral in Brazil, and the other to the island of Principe in the Gulf of Guinea, as these would be the best places to observe in order to test the theory.

The expeditions were a success. By marking the positions of stars and comparing them to the same view of the sky when the Sun was not in that position, the astronomers were able to show how the stars had appeared to move.

The solar mass was warping the starlight. Einstein's theory was correct.