Data from NASA's Curiosity rover has thrown light on Mars as having a watery past in which streams flowed and briny pools formed. The findings, based on data returned by Curiosity, suggest the Martian world was once very different from the freezing desert that it is today.

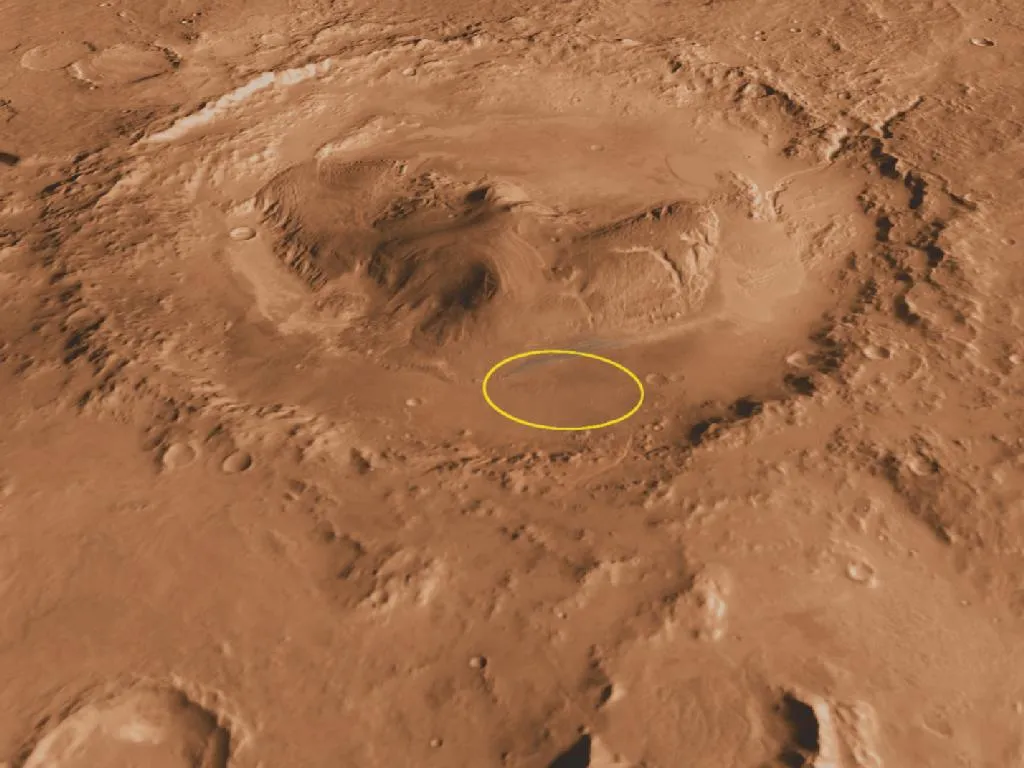

In a paper published in Nature Geoscience, researchers posit a planet in which ponds with fluctuating water levels once dotted the floor of the 150km-wide Gale Crater on Mars, which is currently being studied by Curiosity.

- Mars Express Orbiter reveals Red Planet's volcanic history

- Evidence of liquid water on Mars

- Interview with a NASA rover scientist

Salts found on sedimentary rocks in one 150m-tall section called Sutton Island, visited by Curiosity in 2017, paint a picture of water streaming down into the crater, eventually filling lakes and overflowing, before drying up and then beginning the cycle of filling again.

Mineral deposits on the rocks also suggest these shallow pools were briny.

The idea that water was in flux, continually overflowing and drying, implies a period of transition for the planet’s climate towards a dryer time and also raises questions about when life might have survived on Mars’s surface.

“We went to Gale Crater because it preserves this unique record of a changing Mars,” says the report’s co-author William Rapin.

“Understanding when and how the planet’s climate started evolving is a piece of another puzzle: When and how long was Mars capable of supporting microbial life at the surface?”

The researchers believe the climate fluctuation would not necessarily have progressed smoothly.

“We see an overall trend from a wet landscape to a drier one” says Curiosity Project Scientist Ashwin Vasavada, “but that trend didn’t necessarily occur in a linear fashion.

“More likely, it was messy, including drier periods, like what we’re seeing at Sutton Island, followed by wetter periods, like what we’re seeing in the ‘clay-bearing unit’ that Curiosity is exploring today.”