Astronomers have discovered a pair of blazing black hole objects known as quasars on a collision course with one another in the early Universe.

The two quasars, known as J0749+2255, are found deep within two separate galaxies that collided with each other 10 billion years ago, but the galaxies are so far away it has taken their light that long to reach Earth's observatories.

The quasars are separated by less than the size of a single galaxy.

Quasars and the early Universe

Quasars are cosmic objects that shine with the power of over 100 billion stars.

They’re powered by supermassive black holes consuming cosmic gas and dust, which gets heated to high temperatures and emits a powerful yet fleeting signal.

Quasars’ powerful energy is what enabled astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope and a fleet of other space and ground-based telescopes to find this particular pair, which are so far away we’re seeing them as they existed when the Universe was just 3 billion years old.

"We don't see a lot of double quasars at this early time in the Universe. And that's why this discovery is so exciting," says Yu-Ching Chen of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, lead author of the study, which appears in the Nature journal.

"We're starting to unveil this tip of the iceberg of the early binary quasar population," says Xin Liu of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

"This is the uniqueness of this study. It is actually telling us that this population exists, and now we have a method to identify double quasars that are separated by less than the size of a single galaxy."

A fleet of telescopes

In order to find the quasar duo, the team used an array of humanity's most powerful observatories, including the Hubble Space Telescope, the W.M. Keck Observatory and Gemini Observatory in Hawaii, NSF's Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array in New Mexico and the space-based Chandra X-ray Observatory.

The European Space Agency's Gaia space observatory helped identify this double quasar in the first place.

"Hubble's sensitivity and resolution provided pictures that allow us to rule out other possibilities for what we are seeing," says Chen.

The team note that Hubble, for example, was able to rule out the possibility that this was actually one quasar appearing as two due to gravitational lensing.

This means that light from a single distant quasar could have been distorted and warped by the gravity of a foreground galaxy, making it appear as two separate objects.

The Keck telescope was used to confirm there is no such 'lensing' galaxy between us and the double quasar.

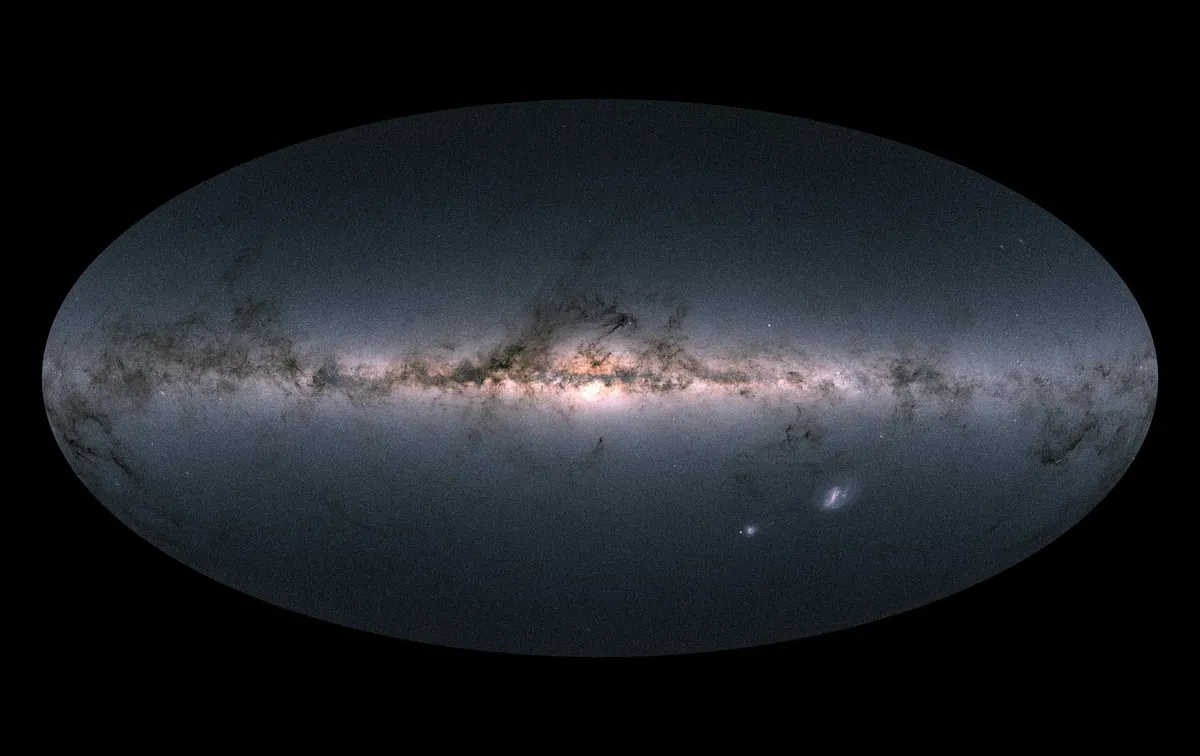

However, it was the Gaia spacecraft, which is currently producing a map of the Milky Way galaxy, that was able to nail down the quasars.

Data from the Gaia mission was used to determine a 'jiggle' in the quasars that made them appear as though they were moving.

In fact, this jiggle could be down to fluctuations in each of the quasar's brightness.

A look back in time

What's perhaps most mind blowing is that this double quasar no longer exists.

The galaxies are so far away, it will have taken 10 billion years for their light to reach us, meaning astronomers are effectively looking back in time to the early Universe.

In that time, the host galaxies have likely merged into a giant elliptical galaxy.

Studies like these can give astronomers greater insight into the the formation of galaxies in the early Universe, as it's thought that large galaxies formed over time through mergers just like this.

"Knowing about the progenitor population of black holes will eventually tell us about the emergence of supermassive black holes in the early Universe, and how frequent those mergers could be," says Chen.

Read more about this story at hubblesite.org/contents/news-releases/2023/news-2023-002.