A black hole has been caught in the act of tearing a star apart, the first time such an act has been directly observed.

The cosmic feast appears to have created a jet of material travelling at nearly the speed of light.

The hungry black hole is located in a pair of colliding galaxies collectively known as Arp 299, and it has taken over a decade of observations to make this discovery, though the results are only just being published now in the journal Science.

The first signs of something unusual in Arp 299 came in January 2005 when astronomers saw a brief burst of infrared coming from the core of the two galaxies and follow-up observations found radio emissions from the same spot.

“As time passed the new object stayed bright at infrared and radio wavelengths, but not in the visible light and X-rays,” says Seppo Mattila of the University of Turku in Finland.

“The most likely explanation is that thick interstellar gas and dust near the galaxy’s centre absorbed the X-rays and visible light, then re-radiated it as infrared.”

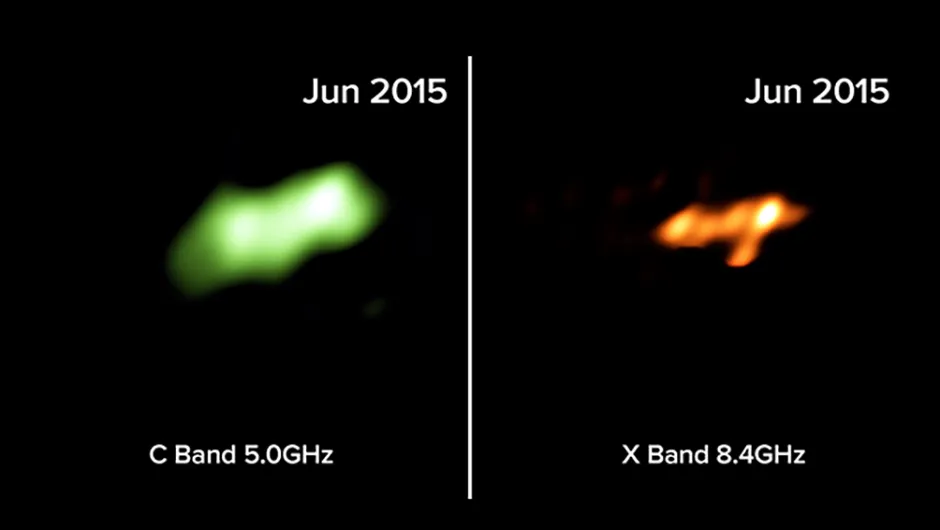

The team continued to observe the object for the next decade using the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) and other radio telescopes and found that the emission seemed to be expanding in one direction, as you would expect to see during the creation of a jet.

Astronomers now think that Arp 299 contains a supermassive black hole that is shredding a star twice the mass of the Sun.

When a black hole pulls apart a star like this, the stellar material can get caught in orbit leading to a chain of events that results in a jet of particles streaming away at near light speed.

“Much of the time, however, supermassive black holes are not actively devouring anything, so they are in a quiet state,” says Miguel Perez-Torres from the Astrophysical Institute of Andalusia in Spain.

“Tidal disruption events can provide us with a unique opportunity to advance our understanding of the formation and evolution of jets in the vicinities of these powerful objects.”

Though this is the first such event to be seen, it is does not necessarily mean they are rare – only hard to spot.

“Because of the dust that absorbed any visible light, this particular tidal disruption event may be just the tip of the iceberg of what until now has been a hidden population,” says Mattila.