There's a supermassive black hole at the centre of our Galaxy, and astronomers have spotted a pair of stars orbiting one another very close-by.

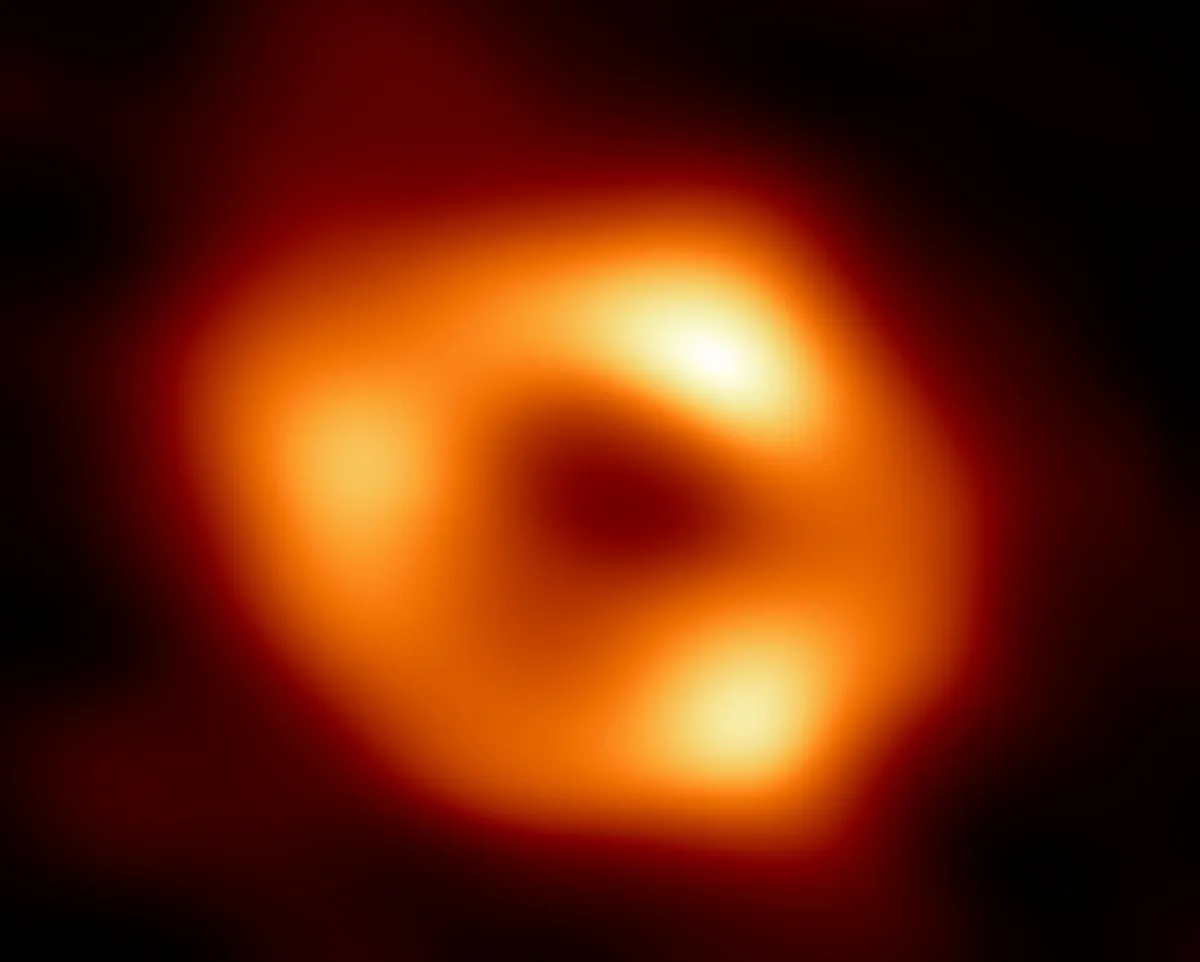

The black hole is known as Sagittarius A*, and is located right at the core of the Milky Way.

Astronomers know there are supermassive black holes at the centres of many large galaxies, and ours is no exception.

In fact, these supermassive black holes likely play a key role in the formation and evolution of galaxies.

Discovering the binary stars

Binary stars are common in the Universe, but none had never been found near a supermassive black hole.

The discovery marks the first time a binary star system has been found near a supermassive black hole, and it's happening right at the centre of our own Galaxy.

Astronomers used data collected by the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope to make the discovery.

They say it's helping build a picture as to how stars survive in environments with extreme gravity.

What's more, it could eventually lead to the detection of planets close to Sagittarius A*.

What it tells us

"Black holes are not as destructive as we thought," says Florian Peißker, researcher at the University of Cologne, Germany, lead author of the study published in Nature Communications.

It seems some binary star systems can thrive even under such extreme conditions.

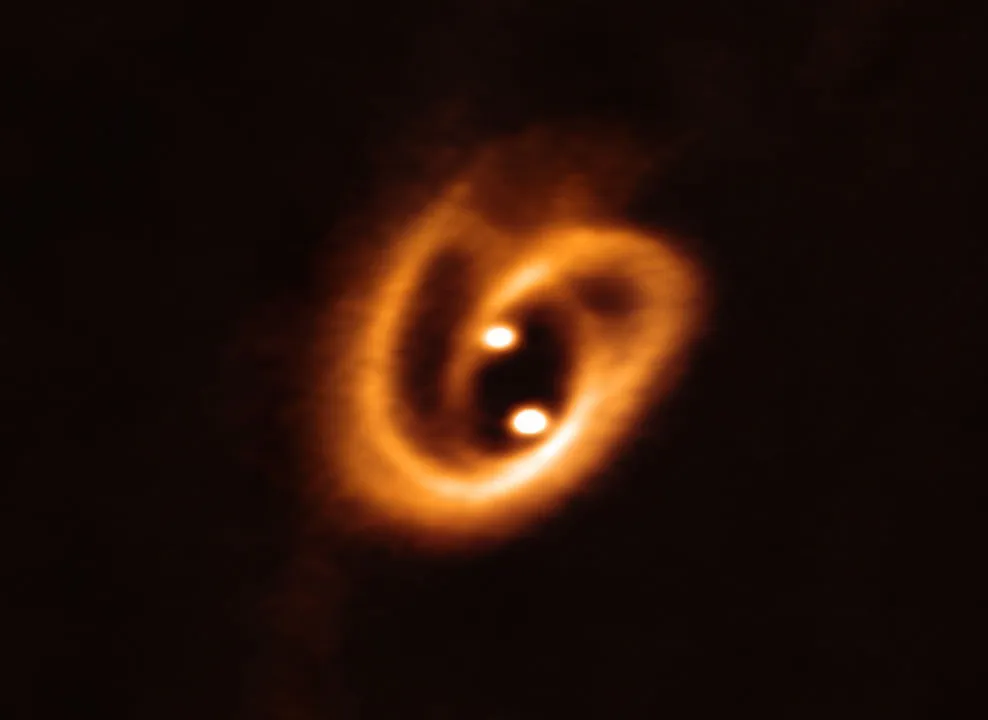

The new pair is called D9 and estimated to be 2.7 million years old, which makes them stellar infants.

But their lives are likely to be short.

The gravitational tug of the supermassive black hole will probably cause the stars to collide and merge into a single star within just 1 million years, the astronomers say.

These timespans are the blink of an eye, in cosmic terms.

"This provides only a brief window on cosmic timescales to observe such a binary system — and we succeeded!" says co-author Emma Bordier, also a researcher at the University of Cologne and a former student at ESO.

So can stars really form near supermassive black holes? It appears so. Several young stars have already been found near Sagittarius A*.

"The D9 system shows clear signs of the presence of gas and dust around the stars, which suggests that it could be a very young stellar system that must have formed in the vicinity of the supermassive black hole,” says co-author Michal Zajaček, a researcher at Masaryk University, Czechia, and the University of Cologne.

How the binary stars were found

The binary stars near Sagittarius A* live in a dense cluster of stars orbiting the black hole, known as the S cluster.

Within the cluster are the so-called 'G objects', which behave like stars but look like clouds of gas and dust.

The astronomers were observing these strange objects and found a strange pattern in D9.

Data gathered by the VLT’s ERIS instrument, together with archival data from the SINFONI instrument, showed recurring variations in the velocity of the star.

"I thought that my analysis was wrong," Peißker says, "but the spectroscopic pattern covered about 15 years, and it was clear this detection is indeed the first binary observed in the S cluster."

Could the mysterious G objects, then, be a combination of binary stars that haven't yet merged, along with debris left over from stars that have already merged?

Many questions remain, but the astronomers say a planned GRAVITY+ upgrade to the VLT Interferometer and the METIS instrument on ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope could help.

These upgrades will enable the team to get an even closer look at the centre of our galaxy.

"Our discovery lets us speculate about the presence of planets, since these are often formed around young stars," says Peißker.

"It seems plausible that the detection of planets in the Galactic centre is just a matter of time."

The research was presented in the paper A binary system in the S cluster close to the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* (PDF) published in Nature Communications (doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-54748-3).