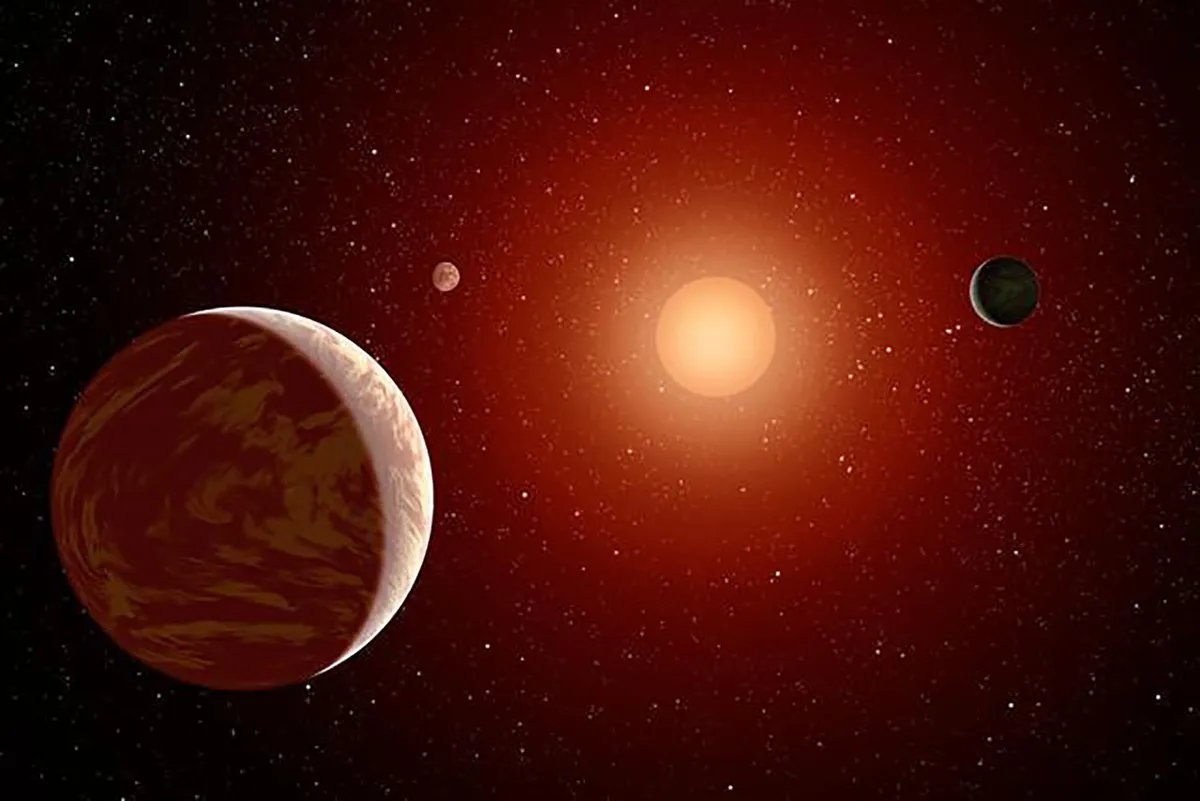

The chances of finding young planets similar to Earth around stars beyond our Solar System is a lot higher than thought, according to a team of researchers from the University of Sheffield.

The results are some of the latest findings in the field of exoplanet research, which looks at planets orbiting distant stars in an attempt to learn more about them.

The Sheffield team have been studying groups of young stars in our Galaxy to learn whether they matched current theories and previous observations of other star-forming regions.

They found there are more stars like our own Sun in these stellar groups than expected, which would increase the likelihood of finding Earth-like planets in the early stages of formation.

How do planets form?

Planets are thought to form from a dusty disc of gas and debris in orbit around a young star, known as a 'protoplanetary disc'.

These discs consist of the remaining material left over from that star's formation, and over time gravity causes dust and debris to coalesce into larger objects, which eventually grow to form planets in orbit around that star.

In these early stages of formation, Earth-like exoplanets known as 'magma-ocean planets' are still forming through collisions with rocks and smaller planetary bodies, which causes them to heat up to the extent that their surfaces are molten rock.

The Sheffield team hope their findings will contribute to our understanding of whether star formation occurs in the same way across the Universe, and will be a resource for further research into the formation of young, rocky, potentially-habitable Earth-like planets. It could also help reveal more clues about what makes a planet habitable.

“These magma ocean planets are easier to detect near stars like the Sun, which are twice as heavy as the average mass star," says Dr Richard Parker from the University of Sheffield’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

"These planets emit so much heat that we will be able to observe the glow from them using the next generation of infra-red telescopes.

"The locations where we would find these planets are so-called ‘young moving groups' which are groups of young stars that are less than 100 million years old - which is young for a star.

"However, they typically only contain a few tens of stars each and previously it was difficult to determine whether we had found all of the stars in each group because they blend into the background of the Milky Way galaxy.

"Observations from the Gaia telescope have helped us to find many more stars in these groups, which enabled us to carry out this study."

The team, led by Dr Richard Parker, also included undergraduate students Amy Bottrill, Molly Haigh, Madeleine Hole and Sarah Theakston.

Read more about this paper via the Astrophysics Journal.

Iain Todd is BBC Sky at Night Magazine's Staff Writer.