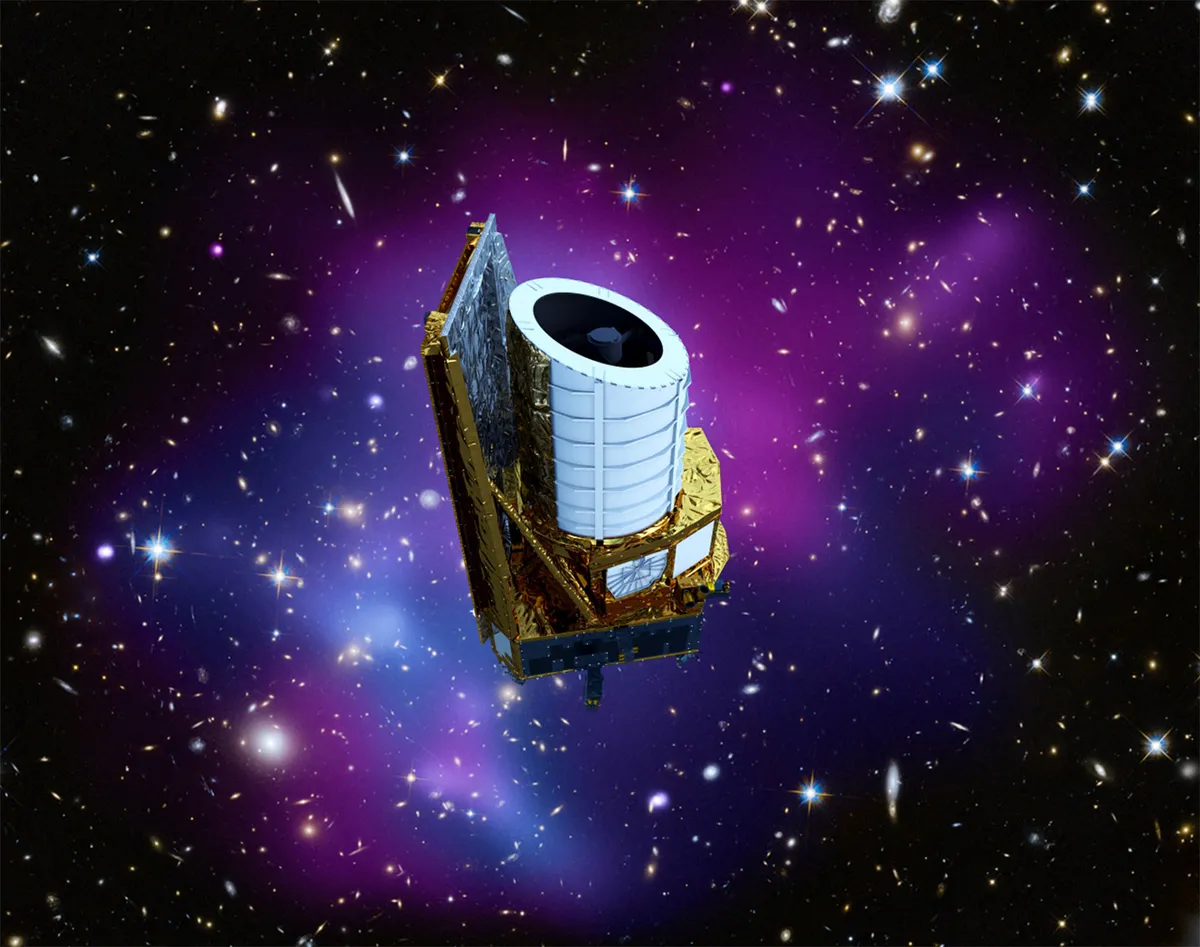

Astronomers have released the first batch of scientific results and images from ESA’s Euclid space telescope.

The images show millions upon millions of galaxies, a dying star shedding its outer layers, and gravitational lenses, where light from distant galaxies is warped by the enormous mass of galaxy clusters.

"This is a taste of what’s to come," says Carole Mundell, ESA’s scientific director. "Euclid is an incredible mission."

More from Euclid

Launched in the summer of 2023 and nicknamed the Dark Universe Detective, Euclid’s main goal is to shed light on two utterly mysterious cosmic ingredients: dark energy (the driving force behind the accelerating expansion of the universe), and dark matter, an invisible substance that prevents galaxies from flying apart.

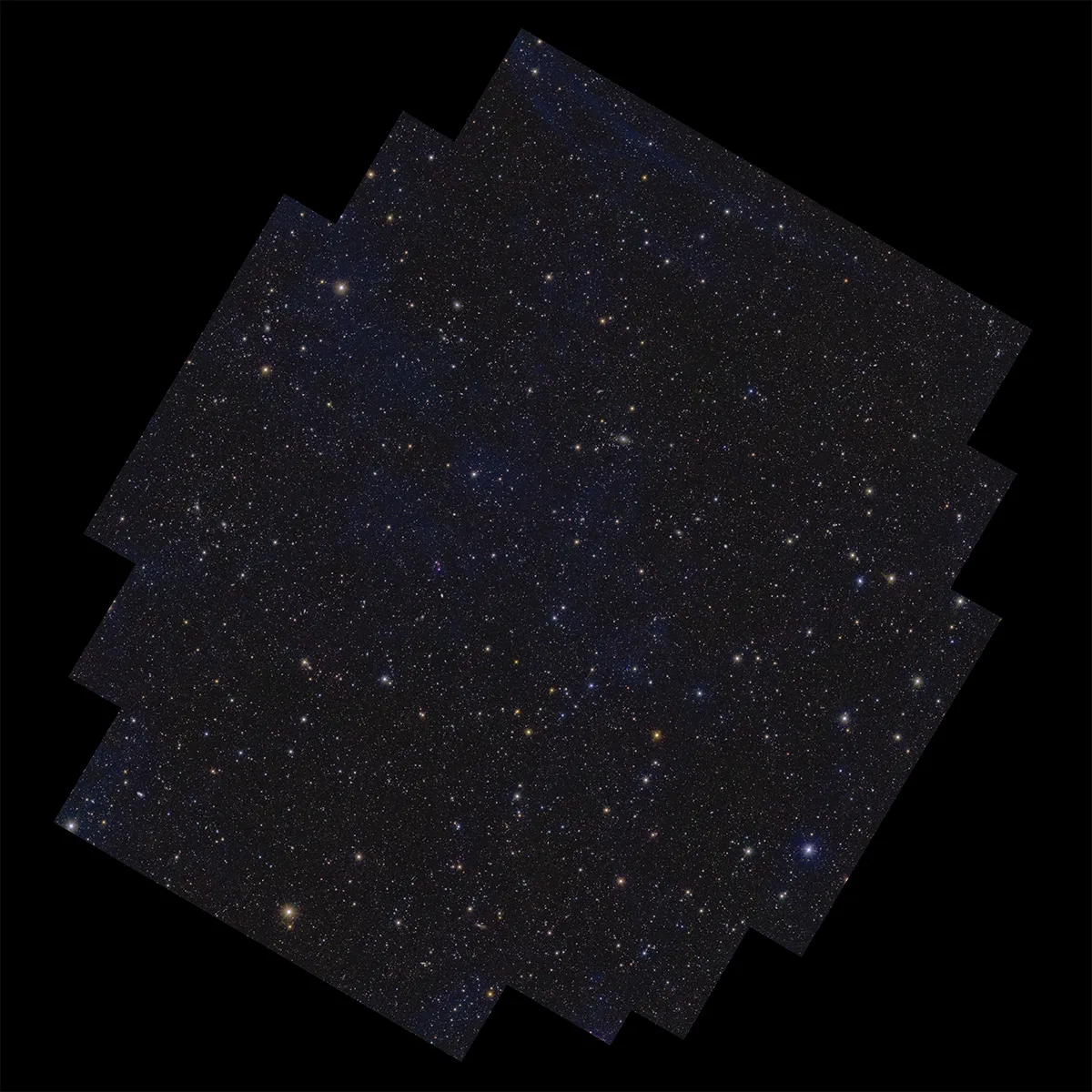

The images released on 19 March 2025 – and described in a series of scientific papers in the European journal Astronomy & Astrophysics – reveal a wealth of remote galaxies in three ‘deep fields’ that will be scanned repeatedly during Euclid’s six-year survey of the sky.

This is a ‘quick’ release from Euclid, of selected areas, to show what sort of data can be expected in future 'major' data releases.

The mission’s first cosmology data will be released in October 2026.

Euclid’s instantaneous field of view covers 2.5 times the area of the full Moon.

"We capture some 250,000 galaxies in just one picture," says project scientist Valeria Pettorino of the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in Noordwijk, The Netherlands.

The three deep field images are mosaics of numerous Euclid exposures.

"In total, they contain 26 million galaxies," says Mundell. "It’s almost impossible to imagine the volume of data that will be available at the end of the mission."

Euclid's science instruments

Euclid sports two science instruments.

The Near Infrared Spectrometer and Photometer (NISP) measures how much a galaxy’s light has been stretched to longer wavelengths by the expansion of the universe.

This so-called redshift is a measure of the object’s distance, and is why galaxies look redder, the further away they are.

The Visible Instrument (VIS) is a 609-million-pixel camera that reveals the precise shapes of galaxies, which are often strongly distorted by the gravity of foreground objects, or more subtly by the overall distribution of gravitating matter, both luminous and dark – an effect known as gravitational lensing.

As Euclid consortium member Koen Kuijken (Leiden Observatory) explains, NISP will yield a 3D map of the distribution of galaxies through time.

"This provides information on the origin and evolution of the large-scale structure of the cosmos, which is governed by dark energy," he says.

Meanwhile, VIS will reveal where the Universe’s gravitating dark matter is concentrated.

"Similar observations have been carried out from the ground," says Kuijken, "but Euclid’s images are much sharper. It’s a great new toy for cosmologists."

Euclid's science

However, it’s too early to draw any conclusions. That can only be done statistically, using the full data set from the six-year survey.

"But the current release is already a big step forward," says gravitational lensing expert and consortium member Henk Hoekstra (Leiden Observatory). "It’s a nice teaser."

Still, this first batch of data is already a real treasure trove.

For instance, Euclid discovered some 500 strong gravitational lenses – more than twice the number that were known to date.

Also, the data led to a detailed catalogue (with accompanying images) of no less than 380,000 galaxies.

To compile both catalogues, scientists used artificial intelligence (machine learning), trained by the results of visual inspection and classification of galaxy images by more than 10,000 volunteers contributing to the Galaxy Zoo citizen science platform.

So far, less than half of a percent of the total Euclid survey area has been observed.

"By the end of the survey, we expect to have found some 100,000 strong gravitational lenses," says Edwin Valentijn (University of Groningen), another Euclid consortium member.

Valentijn helped design the Euclid data information system, utilizing a dedicated European computer network with data centers both in Europe and in the United States.

"It’s working very well," he says. Euclid is transmitting some 850 gigabit of compressed data per day.

In 2026 the first large data release (DR1) will be published, based on Euclid’s first year of operation.

But to Mike Walmsley (University of Toronto), who is also one of the 2,000 or so members of the Euclid consortium, "this is already one of the most exciting weeks in the mission."

UK's contribution to Euclid

Words: Iain Todd

The UK has played a large role in the development of the Euclid mission and its science instruments, and UK astronomers are already benefitting from what it's revealed so far.

Euclid's visible imager (VIS), for example, was designed and built by engineers from University College London and funded by £37 million from the UK Space Agency.

UK scientists and institutions have also developed data processing tools for Euclid, helping astronomers translate the data into discoveries.

Five science papers led by UK researchers have come about as part of this data release.

“Previously, astronomers like me used wide low-resolution surveys to find strong lenses and then requested Hubble for follow-up observations," says Professor Adam Amara, Chief Scientist at the UK Space Agency.

"Now, Euclid accomplishes both tasks in one shot.

“This data release is the first clear evidence that Euclid will be a unique rare object finder (as well as an exquisite dark energy measuring machine).

"In terms of rare objects in the universe, I'm excited to see what 'unknown-unknowns' it will discover - it's been a long wait."