Mega constellations from private space companies such as SpaceX’s Starlink and Amazon’s upcoming Project Kuiper have become an increasingly pressing topic in astronomy circles in recent years. Consisting of networks of hundreds, thousands or even tens of thousands of satellites, they have the potential to provide telecommunications and broadband internet to all corners of the globe.

However, the huge number of satellites required is already making its mark on our night sky, as Ian Christensen, a director at the Secure World Foundation, found out last summer. While out at a US National Park, he noticed a train of dots crossing the Milky Way – an unexpected form of light pollution creeping above the International Dark Sky site. It was Starlink, SpaceX’s mega constellation of communications satellites.

“For me it was a crystallisation of here’s a system with benefits but also a direct and discernible impact of how we as a species engage with the environment,” he told delegates at the Abu Dhabi Space Debate in December 2022.

The two-day meeting organised by the United Arab Emirates was the first-ever international meeting solely dedicated to addressing new space challenges on a global scale.

With rising numbers of new and varied players in space, disparate and out-of-date rules, and tensions rising on Earth, the Space Debate aimed to provide a high-level forum to discuss the future of space – including the role of private space companies and mega constellations.

Low-Earth orbit congested

With access to space becoming easier and cheaper, there are huge opportunities to be had, but there are also concerns. One such major concern is that space is becoming increasingly congested, especially in low Earth-orbit (LEO).

In 2019, there were about 800 active satellites in LEO. At the time of the debate there were roughly 6,000. By the end of 2023, there could be as many as 10,000.

And it is mega constellations that are increasingly dominating the orbit. Half of satellites flying today are part of SpaceX’s Starlink, and the company has permission to launch up to a staggering 42,000.

It’s becoming increasingly clear that LEO is a finite resource.

“While some may look at the possibility of endless exploitation as perhaps our ancestors looked at the oceans, we know that there are limits,” said Adnan Al Muhairi, chief technology officer of satellite company Yahsat. “We have over 250 new companies that have made announcements for constellations. Some are looking at tens of thousands [of satellites].”

Effect of mega constellations on astronomy

As well as safety and sustainability issues, the number of satellites has raised concerns for astronomers and stargazers.

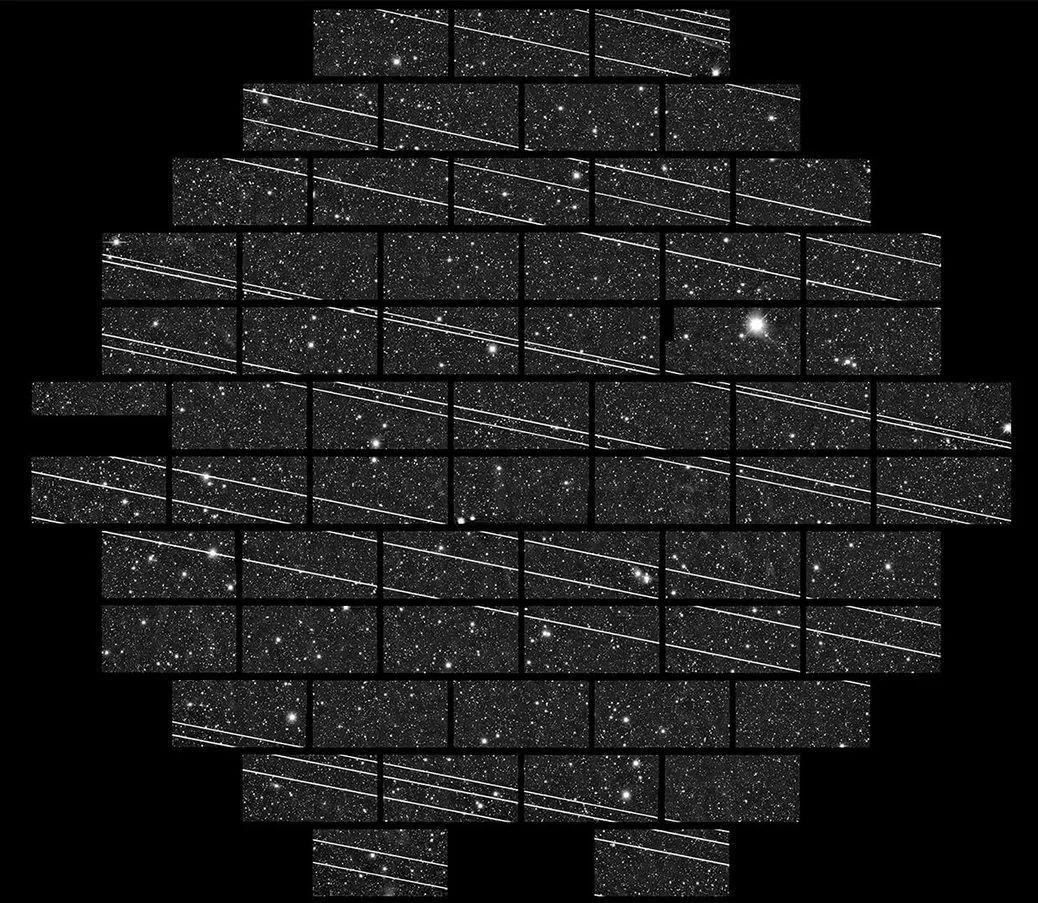

“As these systems have been deployed, we've have found they actually optically interfere with telescope observations,” said Christensen.

“They’re deployed in trains – 50 or 60 in a single launch – and as those satellites transmit across the field of view of terrestrial telescopes, they reflect light back into the telescope and interfere with the ability to collect clean observations.”

Fortunately, there has been much constructive dialogue between the astronomy and satellite operating communities already, leading to the International Astronomical Union establishing a Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Skies to help confront the issue.

Space junk on the rise

It’s not just astronomy under threat, however, as the number of satellites endangers the use of LEO as a whole, due to the increase of space junk.

A fragment of a spacecraft as small as 3cm could cause catastrophic damage to another spacecraft should they strike each other. And the private sector is fully aware that sustainability in space is integral to their businesses.

“It’s on our shoulders to make sure this is safely operated, safely regulated,” says Laith Hamad, from OneWeb. “If you have one collision – only one collision – and you start the Kessler effect then space is of no use to us.”

The Kessler Effect or Syndrome is a situation theorised by NASA scientist Donald Kessler in 1978 where the density of satellites, spent rockets and other space junk becomes so high that it reaches a critical mass and just one collision could trigger a runaway cascade. Each collision creates more debris, which increases the chances of a collision, creating more debris and so on until orbit becomes unusable.

“We are all dependent on space for all aspects of our lives – it’s part of our critical infrastructure,” said Steven Freeland vice-chair of a UN working group on Legal Aspects of Space Resource Activities. “It could put us all back into the Dark Ages.”

If LEO does veer into such a path, the results could be irreversible. While technology such as lasers for active space debris removal or space tracking might offer potential solutions, it isn’t enough.

“Technology in and of itself is not going to solve the problem if we don’t have a radical rethink about how we approach space,” said Freeland.

A global problem

One of the biggest problems, however, is that space is shared between all humanity. There is currently no universal set of rules or agreements that cover all spacefaring nations and the private sector. Nor is there an overarching regulatory or enforcement body, making space potentially a free-for-all.

In 1967, the UN set out a set of rules to govern the space industry, called the Outer Space Treaty. While these are now 50 years-out-of date, they do provide a good basis upon which to build. There have been several other international agreements – most recently 21 countries signed up to the US-led Artemis Accords – but they all address governments and space agencies, not the private sector.

“Do we need a commercial version of these Accords?” asked Mike Gold from Redwire Space, who previously worked for NASA and led the development of the Accords.

While the many challenges were debated at the Abu Dhabi meeting, no agreements were reached other than the general acceptance of the need for discussion and cooperation. “We don’t have the answers – but we needed to start the discussion somewhere,” said His Excellency Omran Sharaf, chair of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space.

One thing was clear however – continuing as business-as-usual is no longer an option. The old systems need to be updated.

“We need to be progressive,” said Sharaf, “Not just address the problem today, but the problems 50, 70 or a 100 years down the line.”