‘Ghost dunes’ have been discovered on Mars, adding another piece to the puzzle of how the Red Planet has undergone environmental changes over the past two billion years.

The discovery will help scientists piece together an impression of how the Martian climate has evolved.

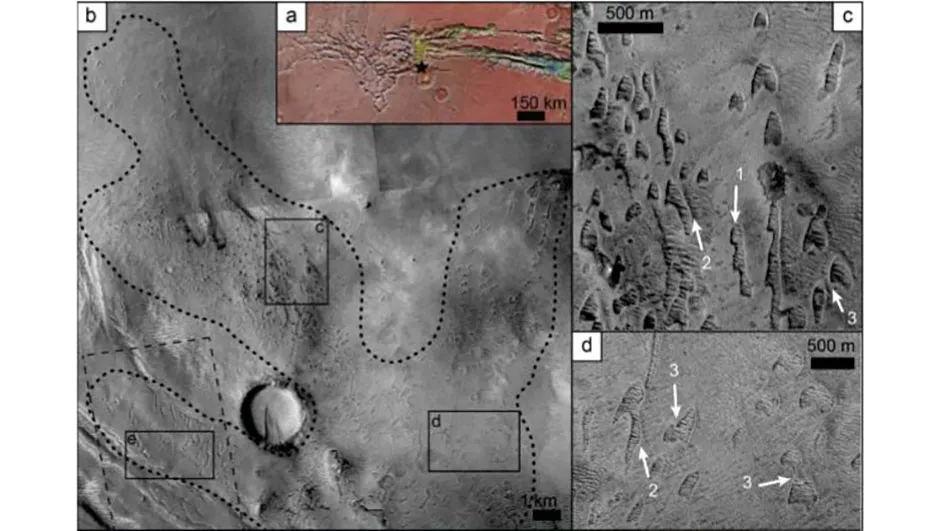

The ghost dunes appear today as crescent-shaped pits, and are thought to be the remnants of sand dunes the size of the US Capitol building, according to the team who made the discovery.

They formed when lava or water-borne sediments partially buried ancient sand dunes and hardened.

Wind then blew sand off the exposed tops and continued removing sand from the inside, leaving behind a hole in the shape of the dune.

Ghost dunes were only discovered on Earth in 2016, in Idaho in the US.

Satellite images of Hellas basin and Noctis Labyrinths on Mars revealed similar formations.

“Any one of these pits is not enough to tell you that it’s a dune, or from an ancient dune field, but when you put them all together, they have so many commonalities with dunes on Mars and on Earth that you have to employ some kind of fantastic explanation to explain them as anything other than dunes,” says Mackenzie Day, a planetary geomorphologist at the University of Washington in Seattle and an author of the study.

Learning more about Martian winds in the past can help scientists calculate how sediments could have been carried over the surface of the planet, and whether its ancient climate differed from that of modern Mars.

“The fact that the wind was different [when the ghost dunes formed] tells us that the environmental conditions on Mars aren’t static over long time scales, they have changed over the past couple billion years, something we need to know to interpret the geology on Mars,” says Day.

The team behind the study used satellite images of Mars to document over 480 potential dune moulds at Noctis Labyrinthus, a collection of plateaus on the Martian equator just west of canyon Valles Marineris.

They also found over 300 crescent-shaped pits in eastern Hellas Planitia, a four billion year old impact crater that stretches over 2,700 kilometres across.

When the dunes formed, Mars had flowing water and active volcanoes.

“If some of the water that carved those valleys made it downstream far enough, it could have gotten to the dune field,” Day says.

“The only thing that we know for sure is that the flow had to be relatively low energy, relatively slow, otherwise it would erode the dunes and we wouldn’t get the shapes that we see today.”