Analysis of Jupiter’s moon Europa suggests that there could be lakes of water just 3km beneath the surface.

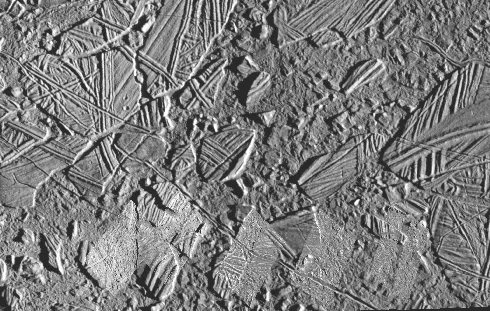

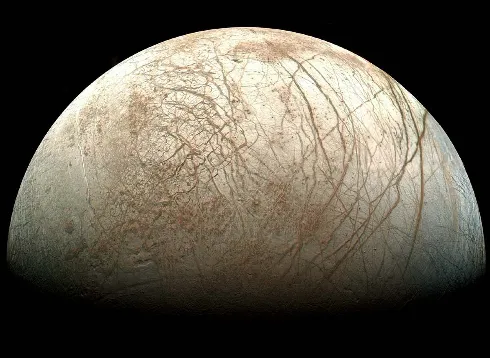

The findings, published in the scientific journal Nature, provide the first working model that might explain the appearance of Europa. Scientists postulated the existence of the lakes by studying images from NASA’s Galileo probe, launched by the Space Shuttle Atlantis in 1989.

Scientists have long theorised that there is a huge ocean, 160km deep, lying 10-30km under Europa’s icy crust. At the moment this makes it essentially unreachable – frustrating to researchers who believe the saltwater ocean, encircling the moon and containing more water than all of Earth’s oceans put together, is a possible location for extraterrestrial life.

Reaching the lakes nearer to the surface would be much more achievable, and their existence gives astrobiologists cause for excitement. The lakes seem to be covered by floating ice shelves that periodically collapse. This means that when the shallower waters mix with the deeper ocean, a mechanism is created for transferring nutrients and energy from the surface, making aquatic life that much easier to sustain.

“One opinion in the scientific community has been if the ice shell is thick, that’s bad for biology. That might mean the surface isn’t communicating with the underlying ocean,” said Britney Schmidt, lead author of the paper from the Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas at Austin. “Now, we see evidence that it’s a thick ice shell that can mix vigorously and new evidence for giant shallow lakes. That could make Europa and its ocean more habitable.”

Europa, discovered by Galileo in 1610, is 563 million km from Earth and 671,000km from Jupiter, which it orbits every 3.55 days. It is tidally locked, keeping the same face towards the planet. The cracks visible on Europa are thought to be due to the stresses and strains exerted by the tidal pull of Jupiter. The icy crust rotates independently of the rocky interior, offering further evidence for the ocean beneath. It has the smoothest surface of any body in the Solar System – there are few craters, suggesting the surface is no more than 30 million years old.

After the NASA/ESA Europa Jupiter System Mission was cancelled, the ESA is looking to go it alone with the Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE). It is a candidate to become a mission within the EAS Cosmic Vision Programme.

Observing the moons

You can see the Galilean moons easily with nothing more than binoculars. In fact you’d see them with the naked eye, given a dark sky, if it weren’t for the overpowering glare of Jupiter itself. It helps to keep the binoculars steady using a tripod or by leaning against a wall.

The moons appear strung out like beads on either side of the planet because the plane of their orbits is roughly oriented to our line of sight. If you can’t see four moons it is probably because one or more lies either in front of or behind Jupiter, or in its shadow. Their positions can be seen to change quite rapidly, making their orbital dances fascinating to watch.

With a 6-inch telescope or bigger at a high magnification, you might be able to spot the dark shadows they cast on the Jupiter’s bright cloud tops, but don’t expect to see any detail.