Vega is one of the brightest stars in the northern hemisphere sky, and new observations by the Hubble Space Telescope and James Webb Space Telescope reveal, surprisingly, it appears to have no planets in orbit around it.

Located in the constellation Lyra, Vega was one of the first stars to be hypothesised to have a dusty disk of material surrounding it.

Then in 1984, observational evidence of this came in the form of an excess of infrared light from warm dust at Vega, detected by NASA's IRAS (Infrared Astronomy Satellite).

This was interpreted as a disk of dust that measured twice the distance of Pluto's orbit around our Sun.

Disks around stars

Where do these disks around stars come from?

Stars form when cosmic material coalesces, grows and grows until it's so massive, it collapses under its own gravity and forms a young protostar.

Any leftover material forms a dusty disk in orbit around that star, and over time, orbiting planets may grow out of this material.

As a result, disks around stars are good places to look for newly-emerging planets.

And mature stars like Vega's disks are full of collisions between orbiting asteroids and debris from comets.

Observing Vega's disk

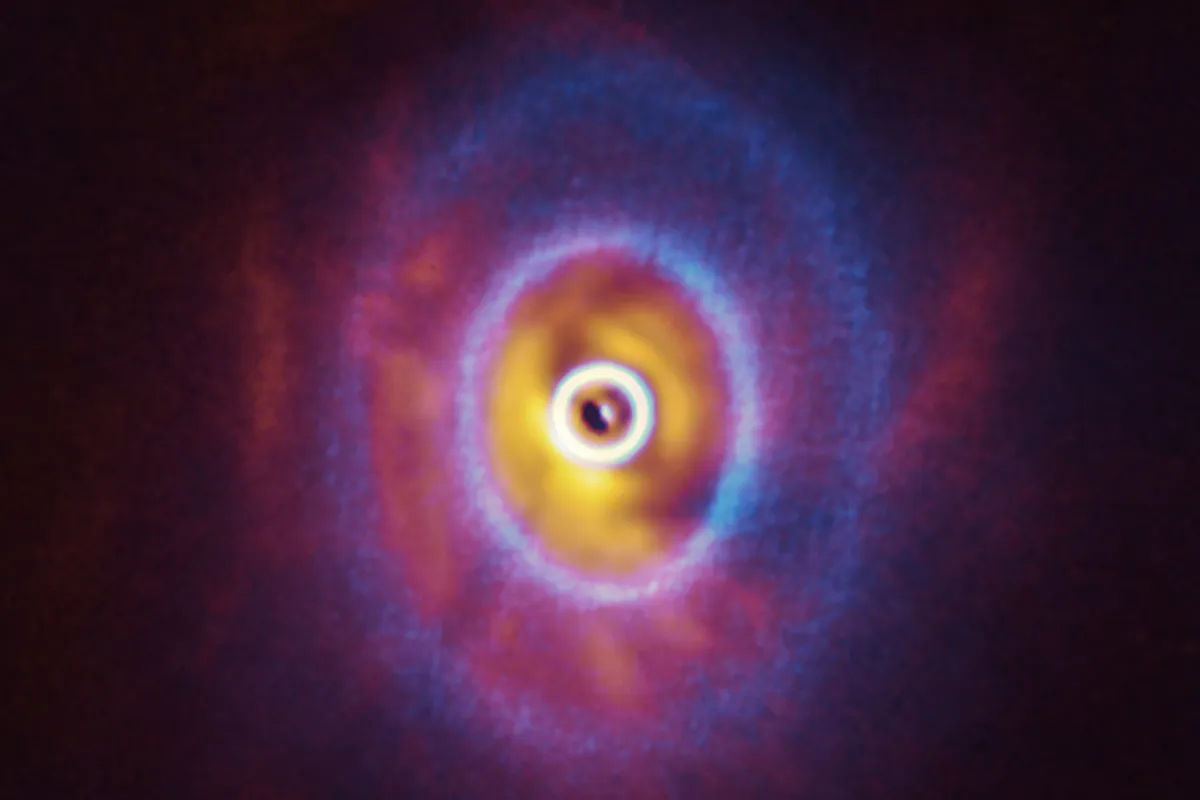

Astronomers at the University of Arizona, Tucson used Hubble and Webb space to observe the disk around Vega, which stretches for nearly 100 billion miles.

If there were planets in orbit around Vega, you might expect to find gaps or ripples in the dusty disc, formed as planets push the cosmic material aside.

And yet, Vega's disk is surprisingly smooth.

"Between the Hubble and Webb telescopes, you get this very clear view of Vega. It's a mysterious system because it's unlike other circumstellar disks we've looked at," says Andras Gáspár of the University of Arizona, a member of the research team.

"The Vega disk is smooth, ridiculously smooth."

There is no obvious evidence for any large planets around Vega.

"It's making us rethink the range and variety among exoplanet systems," says Kate Su of the University of Arizona, lead author of the paper.

What the observations reveal

Webb's infrared vision sees a glowing disk of particles the size of sand around Vega, 40 times brighter than our Sun.

Hubble sees the outer halo of the disk, with particles no bigger than smoke, reflecting starlight.

There are visible layers within the dusty disk surrounding Vega but, say astronomers, this is because the pressure of starlight is pushing out smaller grains faster than larger grains.

And there is a small, subtle gap in Vega's disk around 60 astronomical units from the star (twice the distance of Neptune from the Sun), but otherwise it's smooth.

"Different types of physics will locate different-sized particles at different locations," says Schuyler Wolff of the University of Arizona team, lead author of the paper presenting the Hubble findings.

"The fact that we're seeing dust particle sizes sorted out can help us understand the underlying dynamics in circumstellar disks."

"We're seeing in detail how much variety there is among circumstellar disks, and how that variety is tied into the underlying planetary systems. We’re finding a lot out about the planetary systems – even when we can’t see what might be hidden planets," says Su.

"There are still a lot of unknowns in the planet-formation process, and I think these new observations of Vega are going to help constrain models of planet formation."

Read the full papers at arxiv.org/pdf/2410.24042 (PDF) and arxiv.org/pdf/2410.23636 (PDF).