The briefly-glinting satellites known as Iridium flares that have become so beloved of stargazers and astrophotographers in the last 20 years will cease to be at the end of 2018, Iridium Communications has confirmed to BBC Sky At Night magazine.

The 66 mobile satellite communications satellites in low Earth orbit owned by Iridium all have three reflective panels that occasionally catch the Sun and flare for between five and 20 seconds.

They can be as bright as magnitude -8, which is brighter than Venus, and over the years have become the target of many astrophotographers and astronomers, keen to see how many they can spot.

Websites and apps including Heavens Above, Stellarium, CalSky and CelesTrakare dedicated to predicting them, but not for much longer.

Iridium is now halfway through a launch programme with SpaceX to replace its entire fleet with a smaller, non-flaring fleet of Iridium NEXT satellites; a process that involves de-orbiting all of its older hardware.

“Of the 66 original satellites, we've de-orbited two completely, and four more are on the way, but as we continue to launch we'll continue to de-orbit,” says Matt Desch, CEO of Iridium Communications.

Iridium 30 and 77 both burned up in Earth's atmosphere in September 2017, while the company just launched a third instalment of 10 satellites on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket on 8 October, 2017.

The fourth will follow on 22 December, 2017.

"The final launch will be in June 2018, and by autumn 2018 we will not need any more of the original satellites," says Desch, "so in terms of satellites that are under our control and still predictably flare, the last one will be around the end of 2018."

However, occasional and erratic observations of Iridium satellites will still be possible for some time, Desch confirms.

"The majority will be de-orbiting within a year, but you might see some tumbling flares for a period of time into 2019 – and some of the satellites might take as long as 20 years to come down."

Some of the first generation of Iridium satellites have been in a near-polar Earth orbit, at an altitude of 786km and an inclination of 86°, since May 1997.

The ceasing of predictable Iridium flares will sadden a niche of dedicated astrophotographers set on capturing every single Iridium satellite currently in orbit.

“I absolutely love Iridium flares and I've photographed about 170,” says Mary McIntyre, who has been imaging them for several years.

“I'm desperately trying to complete the set of active Iridiums still in orbit before they are replaced.”

That's something fellow iridium-collector Andy Stones has done, and all with just an iPhone.

“I started to image them in 2013, and when I realised I was gathering a lot of images, I found a site that listed them all and took it from there," he says.

"They are a delight to see in the night sky, especially the really bright ones," agrees amateur astronomer David Blanchflower (@DavidBflower) from Newcastle upon Tyne.

"Not being able to witness them again will be a great loss."

"I'd seen photos from other amateur astronomers online and saw how beautiful these man-made objects in the night sky could be," says Nikki Young (@astro_niks) from Passfield in Hampshire.

Iridium flares were the first night-sky subject Young photographed when she bought a DSLR camera four years ago.

"It's quite an addiction," she says.

For Steven Brown (@sjb_astro) from Stokesley in North Yorkshire, Iridium satellites have become part of his regular observing routine, and he's been taking pictures of their flares for the past three and a half years.

"When I saw my first one I was amazed by the beauty of it; a star-like point of light moving against the dark sky that gradually brightened over a few seconds to become almost dazzling before fading again," he says.

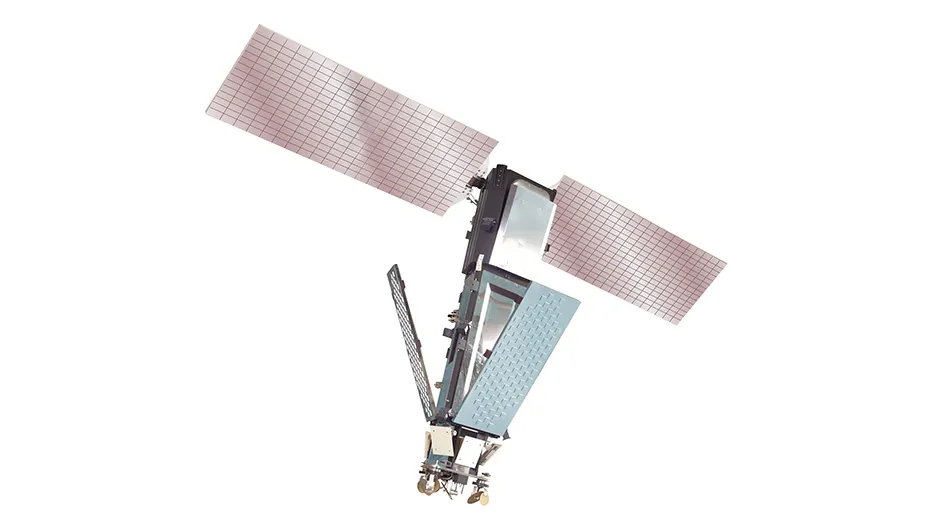

Technological progress and miniaturisation go hand in hand, and that's why Iridium's new fleet of satellites won't flare.

“The design we chose for the Iridium NEXT satellites has a flat bottom and a phased array antenna, so we knew they wouldn't flare, but it was a bit disappointing because we feel the same way as the enthusiasts do,” says Desch.

“We've been working with these satellites, talking to them, controlling them, fixing them and maintaining them all for so many years, and to occasionally get a glimpse of them is exciting.”

Over the next 12 months, Iridium has requested that flare-hunters around the world use the hashtag #flarewell when uploading images of its doomed satellites to social media.

"I will miss capturing these jewels of the night sky on camera, but there are other satellites up there which produce some impressive flares," says Young, name-checking the Metop, Cosmo Skymed & ALOS satellites.

"I'm upset about their impending demise," says Brown of the Iridium satellites.

"I know that technology must move on, but I've really enjoyed the flares over the years.

"The night sky will be a little less interesting without them."