Heat generated by friction inside Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus may be driving its hydrothermal activity, and could do so for billions of years, according to a study using data from NASA’s Cassini mission.

The Cassini mission ended in September 2017, but scientists continue to analyse its data to learn more about Saturn and its moons.

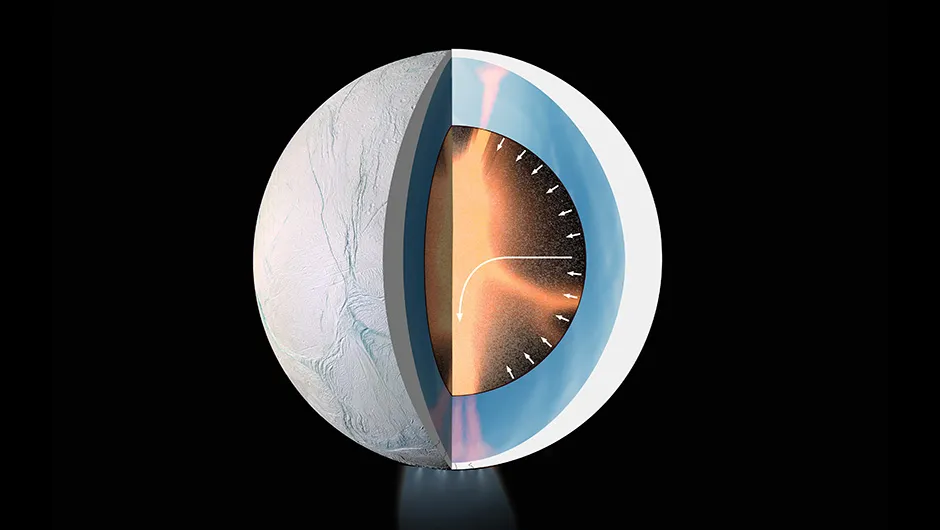

Cassini revealed plumes of water vapour and icy particles spray out from beneath the surface of Enceladus, and that the moon has a global ocean beneath its icy crust.

Evidence pieced together from Cassini data suggests hydrothermal activity - hot water chemically interacting with rock - is taking place on Enceladus’s sea floor.

One clue is the detection of tiny grains of rock, which scientists believe could be the product of hydrothermal activity occurring at temperatures of about 90°C.

The amount of energy required to produce such high temperature could not be provided by the decay of radioactive elements, ruling this possibility out.

Gaël Choblet from the University of Nantes in France worked within a team that calculated a loose, rocky core in Enceladus could generate the required energy.

Their study found that as Enceladus orbits Saturn, rocks in the moon’s porous core could rub together, generating heat.

The loose interior of the core would also allow water from the ocean to penetrate deep down, before heating up and then rising to react with the rocks.

Plumes of water, now warm and containing minerals, hurtle upward, thinning the moon’s icy shell and bursting through fractures in the ice.