Liquid water has been found on Mars. The underground reservoirs could provide a potential habitat for Martian life, but unfortunately we’ll probably never know as the water is located up to 20km (13 miles) below the surface.

The presence of river channels, deltas and water-altered rocks on Mars mean it’s now widely believed that water flowed across Mars until around three billion years ago.

The big mystery, however, is where that water went.

Evidence of liquid water below the surface of Mars was found by ESA's Mars Express mission in 2018

Though some evaporated into space, this can’t explain all the water loss.

Geologists had suspected the rest may have gone underground, potentially creating habitable havens where Martian life has been able to thrive.

"Understanding the Martian water cycle is critical for understanding the evolution of the climate, surface and interior," says Vashan Wright, from the University of California San Diego, who conducted the study while at the University of California, Berkeley.

"A useful starting point is to identify where water is and how much is there."

How InSight found water on Mars

Wright’s team searched for the potential water using NASA’s InSight lander, which listened for Martian seismic activity from 2018 to 2022.

As the vibrations from these marsquakes travelled through the planet, the data allowed the team to look beneath Mars’s surface.

This revealed enough water to cover the entire planet’s surface up to a depth of 1–2km (around a mile).

"Establishing that there is a big reservoir of liquid water provides some window into what the climate was like or could be like," says Michael Manga from UC Berkeley who took part in the study.

"I don’t see why the underground reservoir is not a habitable environment."

Verifying its potential habitability will prove tricky, however, as the water is 11.5–20km (7 to 13 miles) beneath the surface.

"We haven’t found any evidence for life on Mars, but at least we have identified a place that should, in principle, be able to sustain life," says Manga.

More missions to Mars?

Words: Chris Lintott

InSight is the least heralded of NASA’s missions to Mars – not a billion-dollar rover, but a static platform for experiments.

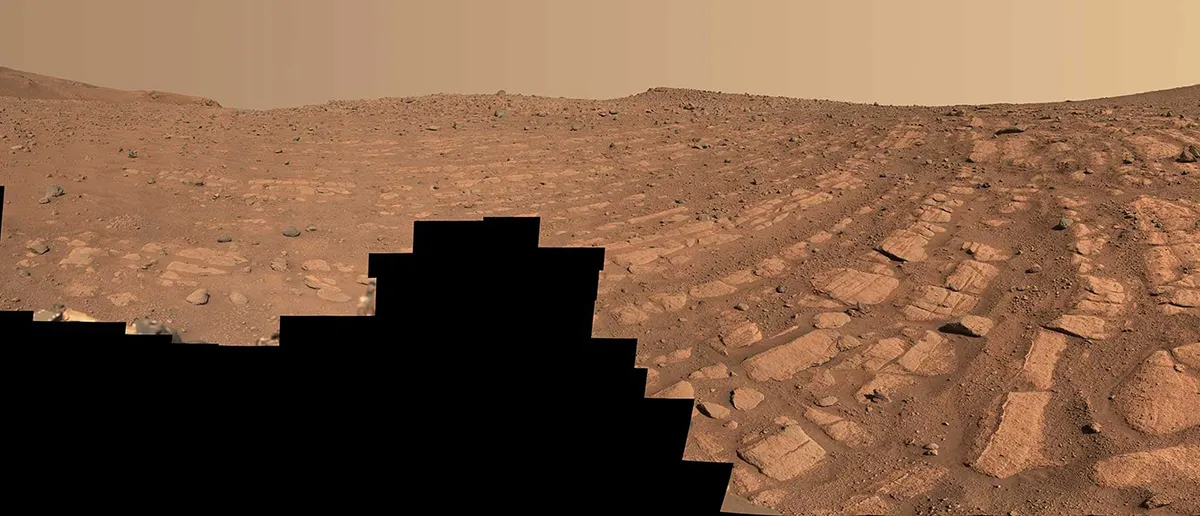

Instead of sending back images of magnificent vistas, it was deliberately sent to the most boring place imaginable, what its team called the biggest parking lot on Mars.

And its most novel experiment, a probe called the ‘mole’ that was supposed to dig into the Martian soil, didn’t work.

Yet it’s this lander that provided the data for this discovery.

It follows previous discoveries by relatively modest missions, like Mars Phoenix and Mars Express, which found ice and salty underground lakes.

Maybe we should be sending more cheap probes. Beagle 3, anyone?