Astronomers have spotted a rare burst of light that’s thought to be one of the Universe’s brightest phenomena.

But it has only served to deepen the mystery of what causes these unusual events.

Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients (LFBOTs) are very blue in colour and evolve rapidly, reaching peak brightness and fading away in a matter of days.

Their short-lived nature makes them difficult to spot, and the first, dubbed ‘the Cow’, was only discovered in 2018.

Since then, they’ve been spotted at a rate of about one per year, mostly in the spiral arms of local galaxies.

That led astronomers to believe they were unusual supernovae generated by huge but short-lived stars.

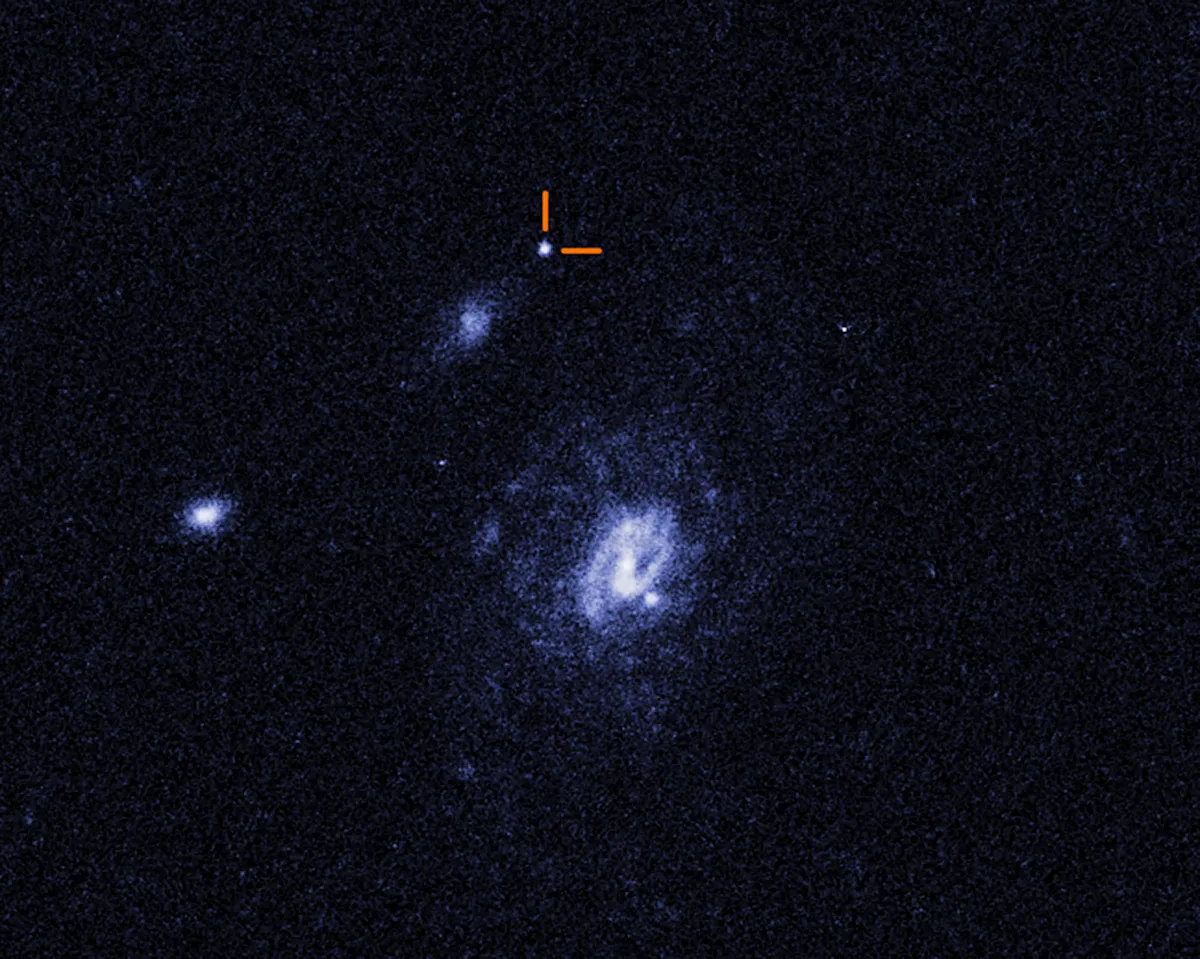

This latest event, though – called AT2023fhn or ‘the Finch’, and first observed on 10 April 2023 – appears to have occurred not within a local galaxy, but in the space between two.

"The more we learn about Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients, the more they surprise us," says European Space Agency research fellow Ashley Chrimes, who led the study.

"We’ve now shown that LFBOTs can occur a long way from the centre of the nearest galaxy, and the location of the Finch is not what we expect for any kind of supernova."

What else could 'the Finch' be?

There are other possible explanations.

It could be that the event is a collision between two neutron stars, where one is highly magnetised and so amplifies the explosion.

Alternatively, Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients could be stars being torn apart by intermediate black holes with a mass between 100 and 1,000 times that of the Sun.

These are thought to lie in globular clusters, which would evade Hubble’s view but could be found in future observations by the James Webb Space Telescope.

"The discovery poses many more questions than it answers," says Chrimes. "More work is needed to figure out which of the many possible explanations is the right one."

Turn to the Vera C Rubin Observatory

Rather than the never-changing cosmos that centuries of astronomers thought they were exploring, modern surveys show a surprising variety of things that go bang in the night.

The Vera C Rubin Observatory will soon start scanning the whole sky every three nights with a 8.4-metre telescope.

In its first tranche of data will be more supernovae than we’ve recorded in human history, all sorts of exotic objects and – hopefully – plenty of Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients.

Almost all the mechanisms suggested for Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients, from colliding black holes to supernovae, must happen out in the Universe, and they should show up in Rubin’s data.

Exciting times, whatever the Finch turns out to be.