Why is Mars red? If you ask a planetary scientist, they might tell you it's due to a type of iron oxide called haematite.

But new research suggests this is not the whole picture, and the study also reveals new insight into water on Mars and the planet's ability to host life.

Using data from European Space Agency and NASA missions, planetary scientists have found that Mars's rust-red dust has a wetter history than previously thought.

It could mean Mars rusted early in its ancient history, when there was much more water on the planet.

Water on ancient Mars

In its ancient history, Mars was much wetter and warmer than the barren landscape we see today.

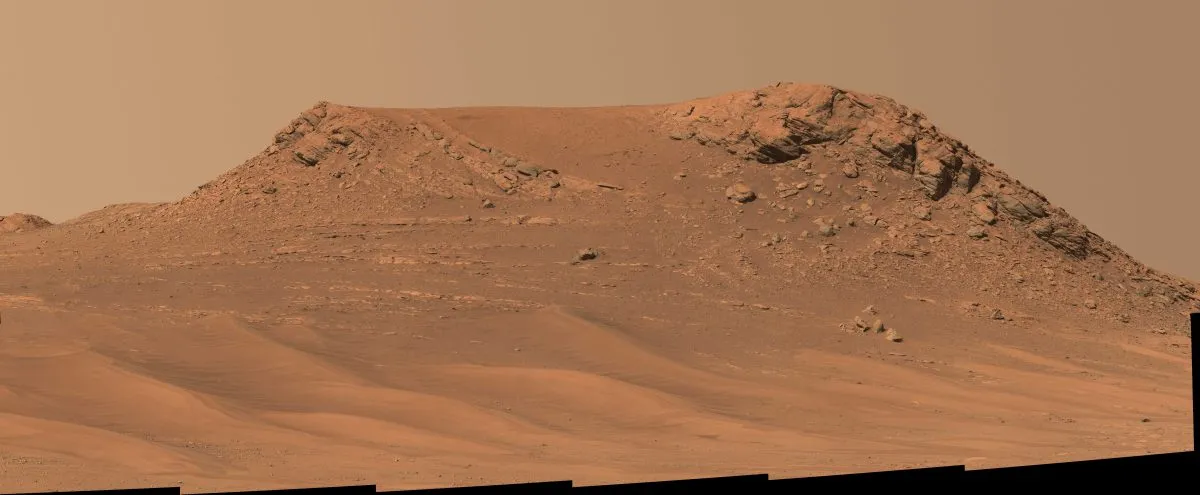

Images sent back by Mars orbiters and rovers show the Red Planet is indeed rusty red, and you can see this for yourself if you observe the planet with the naked eye in the night sky.

At its best, Mars looks like a bright reddish star.

Scientists know Mars's red hue is a result of rusted iron minerals in its dust.

Iron in Martian rocks has reacted with liquid water – or water and oxygen in the air – just like how an iron nail will develop rust on Earth if it's allowed to remain wet and exposed to open air.

This is called 'iron oxide', and on Mars, iron oxide has been broken down into dust and distributed around the planet by Martian winds.

Not just any old iron

There are different forms of iron oxide, and understanding exactly what's going on in the chemistry of Martian dust is key to understanding why Mars is red and the history of water on the Red Planet.

This, in turn, relates to how habitable Mars has been in its history, and how recently.

Scientists say the hematite theory as to why Mars is red is based on studies of iron oxide in Mars dust where spacecraft observations didn't find evidence of water.

This type of iron oxide, according to the available data, must have been hematite, formed under dry conditions through reactions with Mars's atmosphere over billions of years, after Mars had dried up.

Water best matches Mars's red

Mars's red colour is better explained by iron oxides that contain water, known as ferrihydrite, according to this latest study.

The scientists re-analysed data from observations of Mars by spacecraft and carried out lab experiments.

They say ferrihydrite forms in the presence of cool water, so must have formed when Mars still had water on its surface.

What's more, the ferrihydrite has kept its water signature, even though it has been ground down and spread around Mars since its formation.

"We were trying to create a replica martian dust in the laboratory using different types of iron oxide. We found that ferrihydrite mixed with basalt, a volcanic rock, best fits the minerals seen by spacecraft at Mars," says study lead author Adomas Valantinas, a postdoc at Brown University in the USA, formerly at the University of Bern in Switzerland where he began working with ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter data.

"Mars is still the Red Planet. It’s just that our understanding of why Mars is red has been transformed.

"The major implication is that because ferrihydrite could only have formed when water was still present on the surface, Mars rusted earlier than we previously thought.

"Moreover, the ferrihydrite remains stable under present-day conditions on Mars."

Ferrihydrite history

This isn't the first study to suggest ferrihydrite might be present in martian dust, but Adomas and colleagues say they've provided proof by using space mission data combined with lab testing.

They created a replica of Martian dust in a laboratory and analysed the samples using the same techniques adopted by spacecraft on Mars.

This enabled them to identify ferrihydrite as the best match.

Future planned missions to retrieve samples of Martian dust and rock and return them to Earth, however, could solve the mystery as to why Mars is red once and for all.

"This study is the result of the complementary datasets from the fleet of international missions exploring Mars from orbit and at ground level," says Colin Wilson, ESA’s TGO and Mars Express project scientist.

"We eagerly await the results from upcoming missions like ESA’s Rosalind Franklin rover and the NASA-ESA Mars Sample Return, which will allow us to probe deeper into what makes Mars red.

"Some of the samples already collected by NASA’s Perseverance rover and awaiting return to Earth include dust.

"Once we get these precious samples into the lab, we’ll be able to measure exactly how much ferrihydrite the dust contains, and what this means for our understanding of the history of water – and the possibility for life – on Mars."

‘Detection of ferrihydrite in Martian red dust records ancient cold and wet conditions on Mars’ by A. Valantinas et al was published on 25 February 2025 in Nature Communications. Read it here.