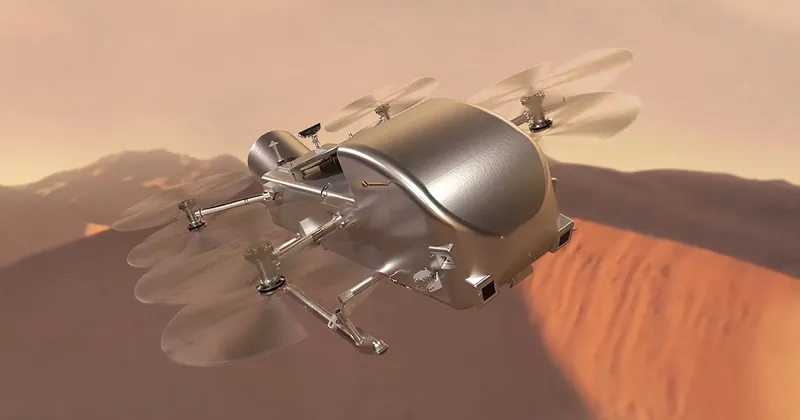

NASA is sending a drone-like probe named Dragonfly to Saturn's largest moon Titan, to search for scientifically interesting locations and find out whether life ever could have existed there.

The mission was conditionally approved in November 2023 and has now been confirmed, meaning that in 2034, if all goes to plan, the space probe will arrive on Titan.

Known as Dragonfly, the NASA rotorcraft probe will fly over the dunes of Titan, exploring and landing at interesting sites for study.

It will investigate Titan's chemistry, where carbon-rich material and liquid water could have mixed for an extended period, and will also explore whether water-based or hydrocarbon-based life could have existed on Titan.

The Dragonfly rotorcraft has eight rotors and will fly like a large drone, and is due to launch in July 2028.

Why Titan?

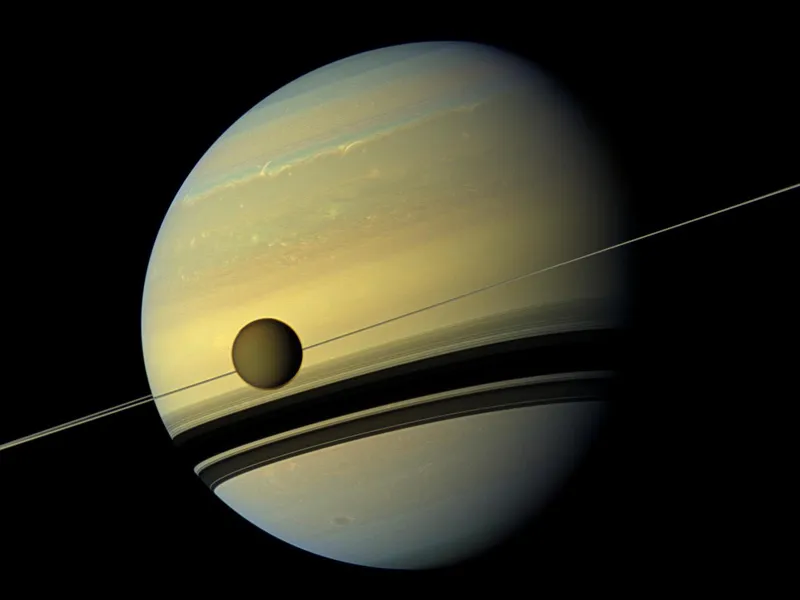

Titan is one of the most Earth-like worlds in the Solar System. Despite being a moon, it has an atmosphere that is nitrogen-based like Earth.

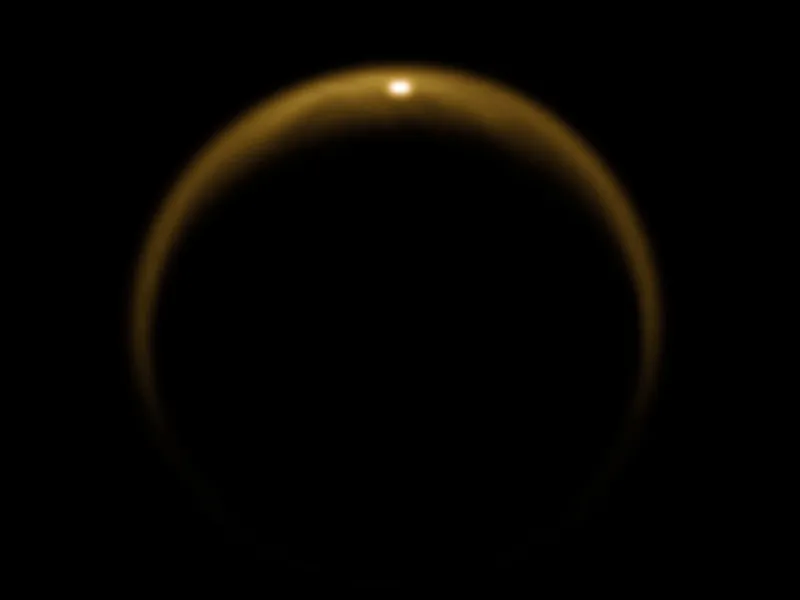

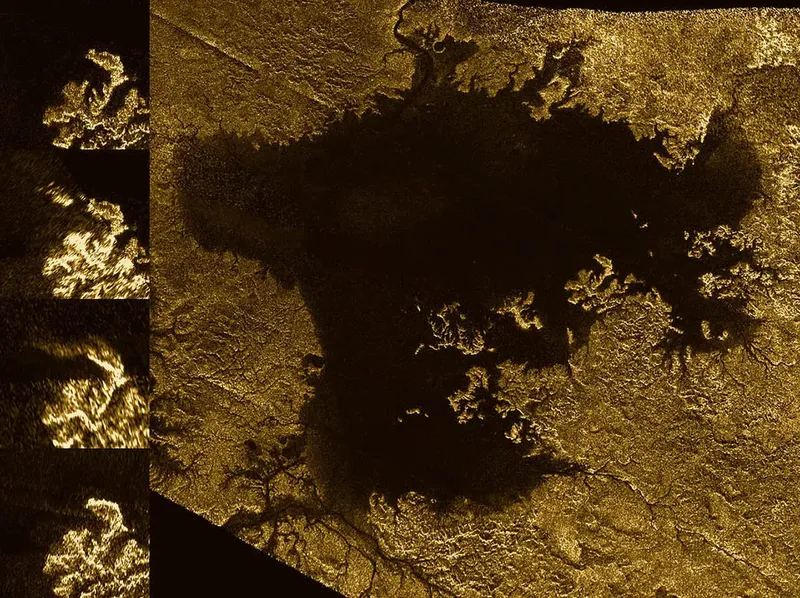

It also has clouds and rain, but rather than water they consist mostly of methane.

Liquid methane falls as rain and pools as a liquid on Titan’s surface.

Other complex organics form in Titan’s atmosphere and fall like snow. It is one of the most promising places in our Solar System to search for signs of life.

What will NASA Dragonfly do at Titan?

Dragonfly will explore multiple environments on Titan, from organic dunes to the floor of an impact crater where liquid water existed with organic material, potentially for tens of thousands of years.

The spacecraft is equipped with instruments to show whether these conditions led to the development of prebiotic chemistry, and to what extent.

Dragonfly will also examine Titan’s atmosphere and its surface, including its subsurface oceans.

It will not be the first spacecraft from Earth to land on Titan.

The Cassini spacecraft spent 13 years exploring Saturn and its moons before ending its mission by making a controlled dive into the ringed planet’s atmosphere on 15 September 2017.

While at the Saturnian system Cassini studied Titan from afar, but also launched the European Space Agency's Huygens lander.

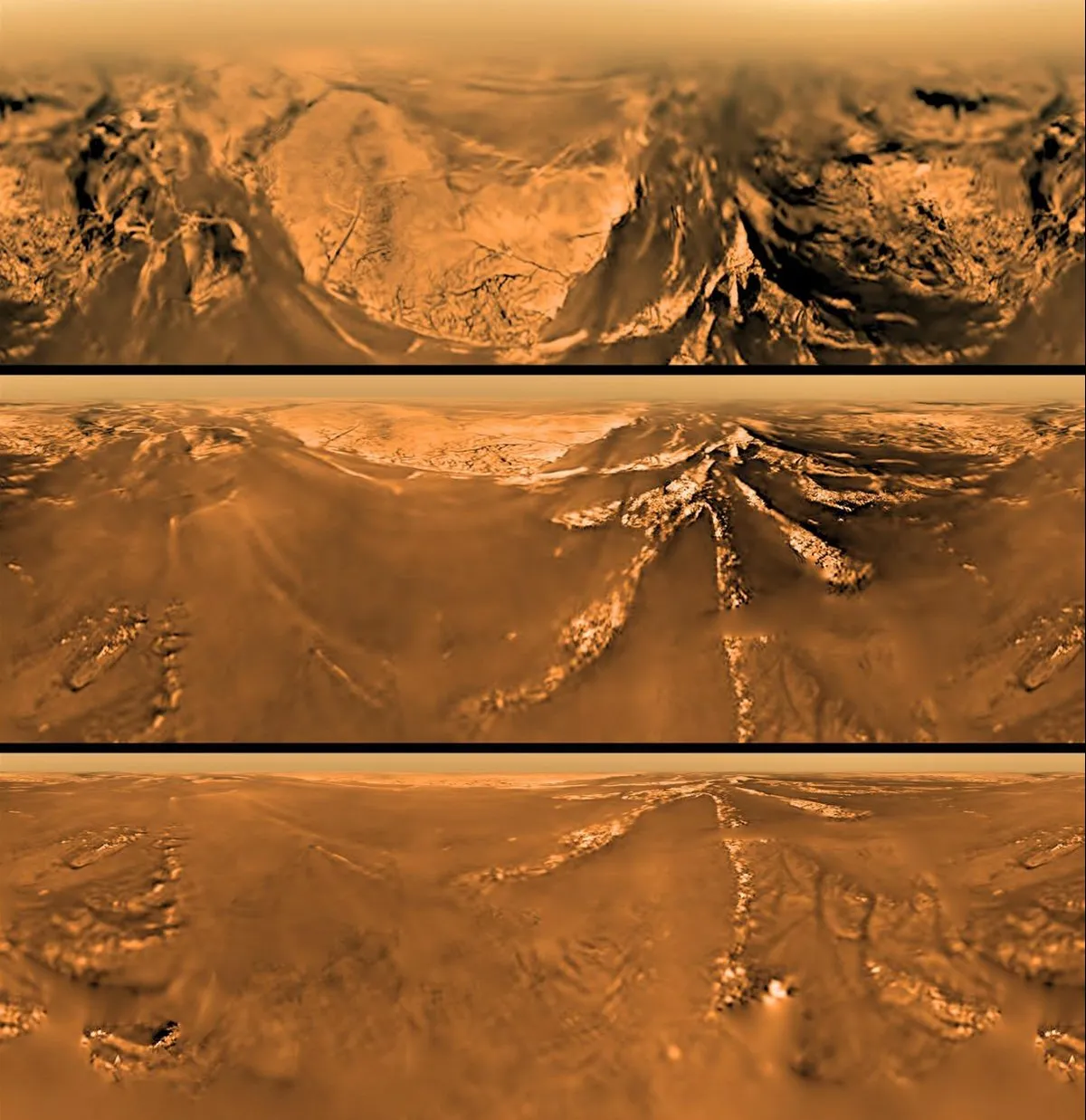

Huygens made a controlled descent onto the surface of Titan in January 2005 giving scientists on Earth their first glimpse of this intriguing icy world.

Cassini data has informed the planing of the Dragonfly mission; specifically helping NASA scientists choose when to land the spacecraft during a calm weather period and which sites on Titan will be best for scientific exploration.

Dragonfly will touch down at Titan's equatorial ‘Shangri-La’ dune fields, which NASA says are similar to dunes in Namibia on Earth.

The spacecraft will conduct short flights in the region, progressing to longer flights of 8km at a time, during which it will sample the surrounding area.

It will then reach Titan’s Selk impact crater, which contains evidence of past liquid water and organics.

These organics - carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen - combine with water on Earth to provide conditions suitable for life to evolve.

Dragonfly will explore whether these conditions were enough to support life on Titan.

The lander will fly over 175km in total; almost double the total distance travelled so far by every Mars rover combined.

“Titan is unlike any other place in the Solar System, and Dragonfly is like no other mission,” says Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s associate administrator for Science.

“It’s remarkable to think of this rotorcraft flying miles and miles across the organic sand dunes of Saturn’s largest moon, exploring the processes that shape this extraordinary environment.

“Dragonfly will visit a world filled with a wide variety of organic compounds, which are the building blocks of life and could teach us about the origin of life itself.”