As part of the publicity for the fly-by of Pluto by the New Horizons probe back in 2015, a NASA app encouraged everyone to go outside and enjoy ‘Pluto time’ – the period after sunset or before dawn when the sky is as bright as it is at midday on the surface of the Kuiper Belt’s most famous denizen.

It was a good way of viscerally understanding quite how far from the warm inner Solar System the plucky little spacecraft had travelled.

New Horizons is now nearly twice as far away as it was then and taking advantage of its isolated position to stare out at the Universe.

Recent observations made by the spacecraft’s team, and reported in a research paper, study the background light that dimly illuminates its journey into interstellar space.

Background light of the cosmos

Paying attention to such background light has a long tradition in astronomy.

The cosmic microwave background provides the best evidence for our Universe’s beginnings in a hot Big Bang, and studies of the X-ray background indicated the presence of exotic objects such as growing black holes long before individual sources were identified.

In the ultraviolet, measuring the brightness of the background can help us check whether our ideas about when and where stars form in the cosmos, as well as the structure of the Milky Way, are right.

New Horizons measures the darkness of space

New Horizons has now flown clear of the bright glow of sunlight that fills the inner Solar System.

When it was 57 AU from the Sun (where 1 AU is the distance between Earth and the Sun), mission operators decided they were in the perfect place to measure the brightness of the far ultraviolet background for the first time, working at wavelengths its Alice spectrometer can see.

This wavelength range is interesting because only the brightest, most massive stars – typically O and B supergiants – can contribute significantly.

But to record their light, the team had to first decide in which direction to look.

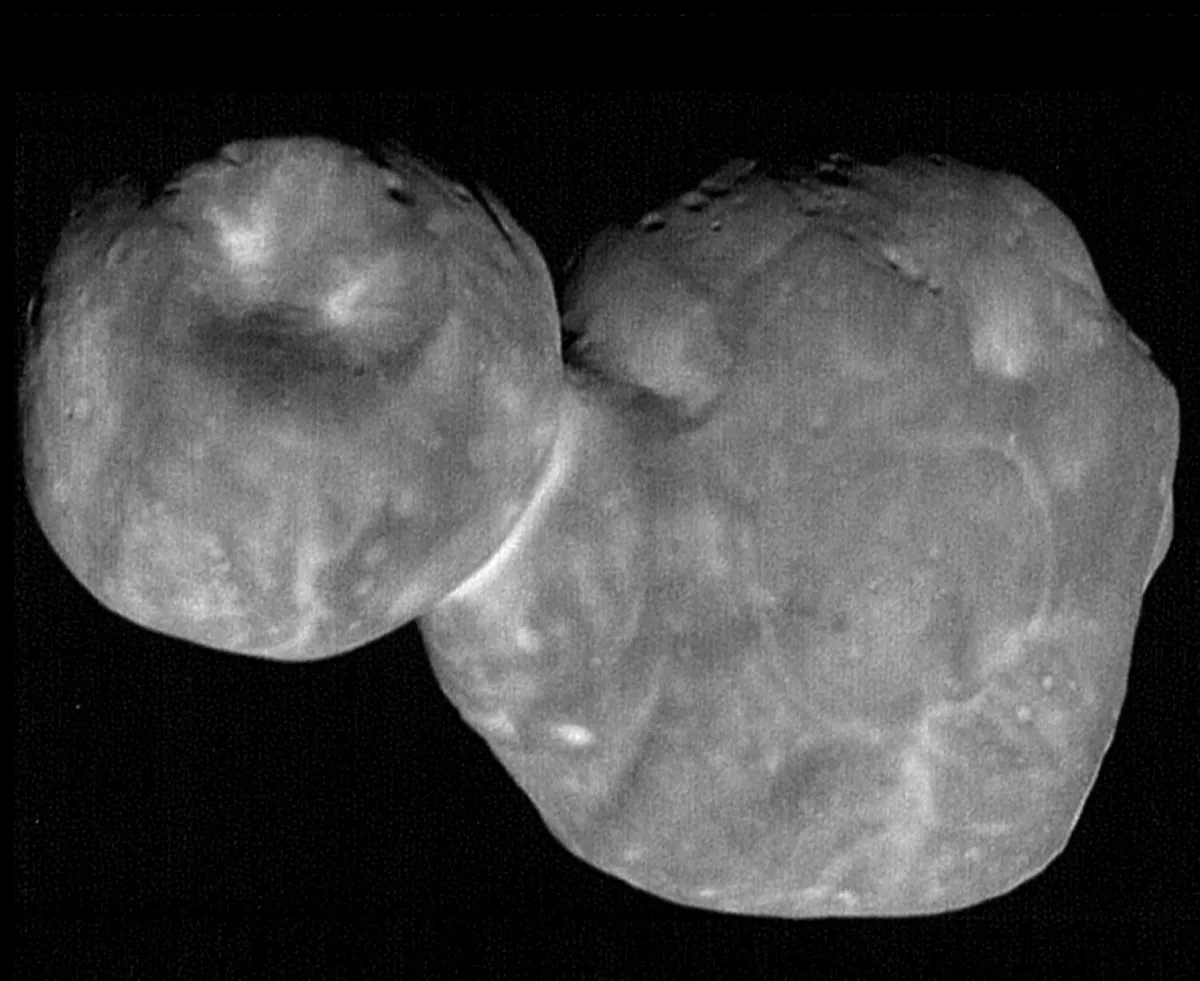

New Horizons’ trajectory was set a long time ago by the manoeuvres that took it past Pluto and, later, tiny Arrokoth, so only the part of the sky that lay in the spacecraft’s shadow, away from the Sun, was available.

It seemed like a good idea to avoid the Milky Way’s disc, so the astronomers looked up to the galactic poles instead.

The results are in...

Over 2023, the team took nearly 200 exposures, each an hour long, of seemingly blank patches of sky, carefully calibrating the results to remove the signal produced by the camera’s electronics themselves.

The result of all this work is a measurement of the background that comes from distant galaxies, from distant stars in the Milky Way, plus the faint glow of hydrogen in our Galaxy’s halo.

The intriguing bit is that the measured background is brighter by a factor of two than we’d expect from all those sources added together.

There is in the Universe a source of ultraviolet light that we have not yet suspected was there. Could there be more faint galaxies than we think?

Perhaps the Milky Way harbours a hidden reservoir of hot gas? Perhaps something even odder is lurking out there.

It’s a proper cosmic mystery, as well as a reminder that being out in the dim outer reaches of the Solar System has its advantages.

Chris Lintott was reading… Excess Ultraviolet Emission at High Galactic Latitudes: A New Horizons View by Jayant Murthy et al. Read it online at: arxiv.org/abs/2501.00787.

This article appeared in the March 2025 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine.