NASA has announced plans to send spacecraft to study Uranus and Neptune.The mission to Neptune is expected to launch in 2029-2030 and Uranus between 2030-2034, in order to use Jupiter’s gravity as a means to assist the spacecraft on their way.

A variety of mission types are being considered including orbiters, flybys and probes that could dive into Uranus’s atmosphere and study its composition.

Uranus and Neptune have only been visited once by human spacecraft: Voyager 2.

This new mission will seek to pick up where Voyager’s scientific discoveries left off, improving our knowledge of the ice systems.

“Exploration of at least one ice giant system is critical to advance our understanding of the Solar System, exoplanetary systems, and to advance our understanding of planetary formation and evolution,” the NASA mission study states.

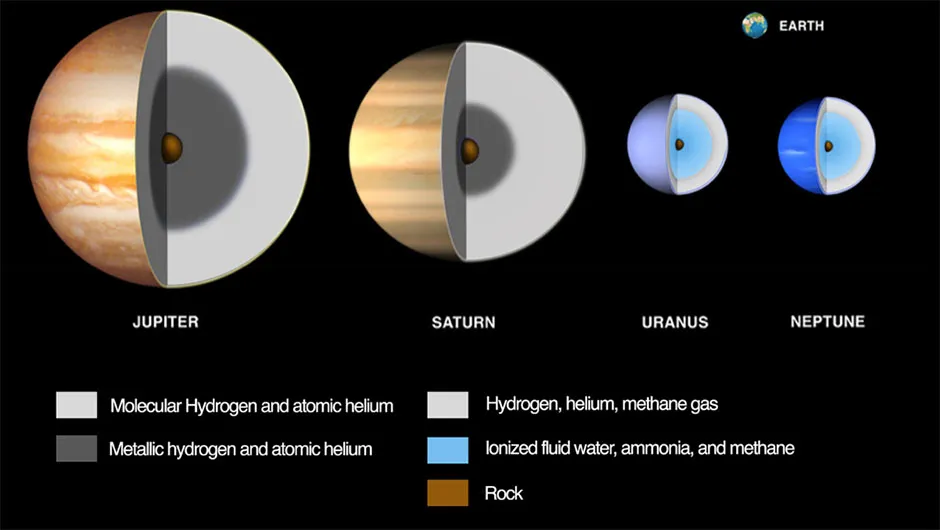

It goes on to say that ice giants are a class of planet not yet well understood, yet are “extremely common” throughout the Galaxy; more so than gas giants like Jupiter.

Models of planetary formation suggest that the ice giants had a narrow timeframe in the history of the Universe during which they could have formed.

Their rocky, icy cores had to have grown large enough to have the gravitational pull to trap hydrogen and helium gas during the early Solar System, when the molecular cloud out of which the planets formed - the solar nebula - was being dissipated by the early Sun.

Had they formed too early, they would have trapped large amounts of gas and become like Jupiter.

Formed too late, they might not have been able to trap enough gas to become the ice giants we know today.

But if they could have only formed within such a tight timeframe, why are they so common in the Milky Way?

This is one of the questions the mission will seek to answer.

The mission will also study the planets' rings, interiors, atmospheres and magnetospheres.

It will also spend time looking at the planets’ moons, recording their shape and geology, mass distribution and internal structure.

Voyager’s flyby of Neptune’s major moon Triton in 1989 led to the discovery of active geysers, so it will also be a target for major study.

Triton is suspected to be a captured Kuiper Belt object, and may have collided with or ejected other major moons that once orbited Neptune.

So, to study native ice giant satellites, a study of the Uranus system will also be necessary: specifically Miranda and Ariel.

"This study argues the importance of exploring at least one of these planets and its entire environment, which includes surprisingly dynamic icy moons, rings, and bizarre magnetic fields," says Mark Hofstadter of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.