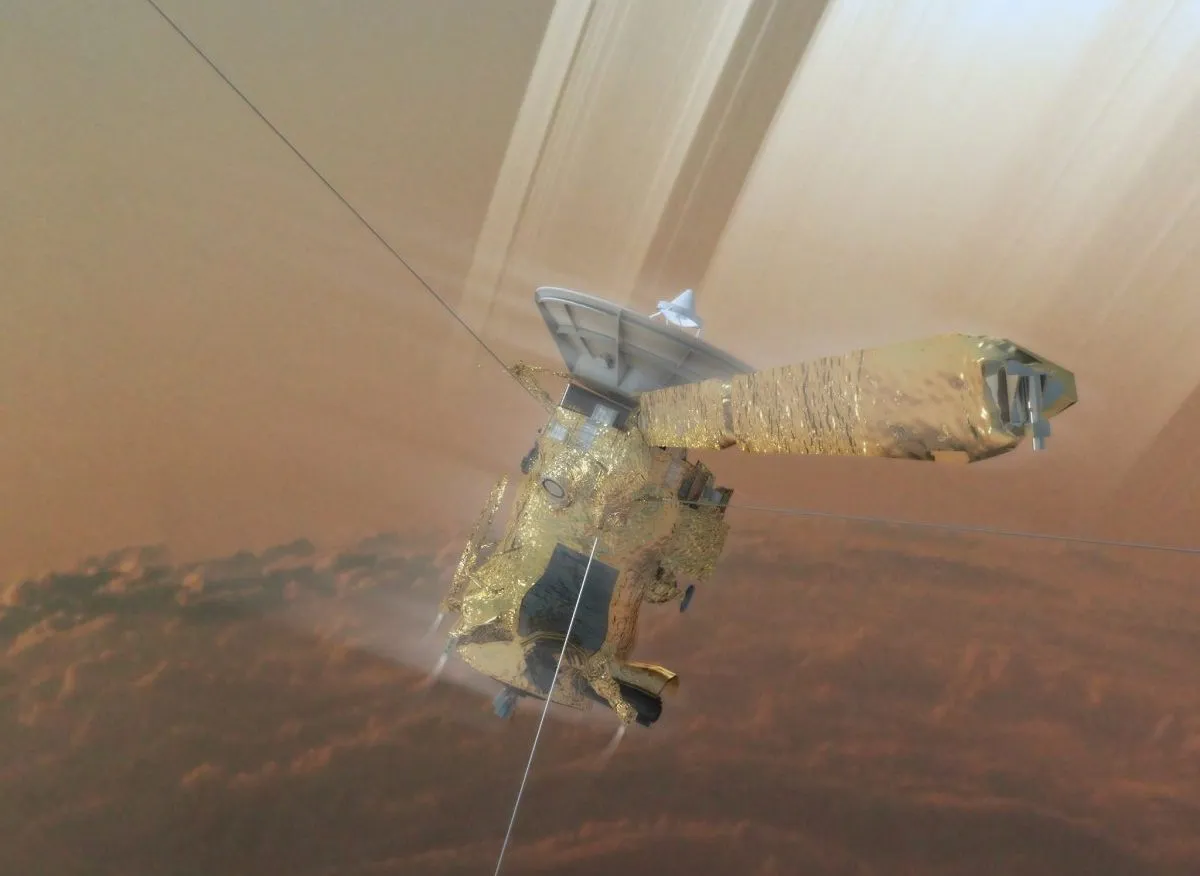

On 15 September 2017 the Cassini mission executed its 'Grand Finale', plunging down to the surface of Saturn and relaying information back to Earth as it descended.

After 20 years in space - 13 of those exploring Saturn - Cassini was ordered to perform a series of risky dives between Saturn and its rings.

Though Cassini's watch may be over, its contribution to science is not, and a new release of analysed Cassini data has revealed more details than ever before, as well as stunning new images.

The paper, published today by a team of international scientists, including STFC-funded scientists Professor Carl Murray and Dr Nick Cooper from Queen Mary University of London, investigates the complex characteristics of Saturn's rings in never-before-seen detail.

Data from the paper was collected during Cassini's Ring Grazing Orbits, from December 2016 to April 2017, and the Grand Finale itself, from April to September 2017.

Here's a look at the remarkable insight the new research and images give into Saturn's rings.

Making waves

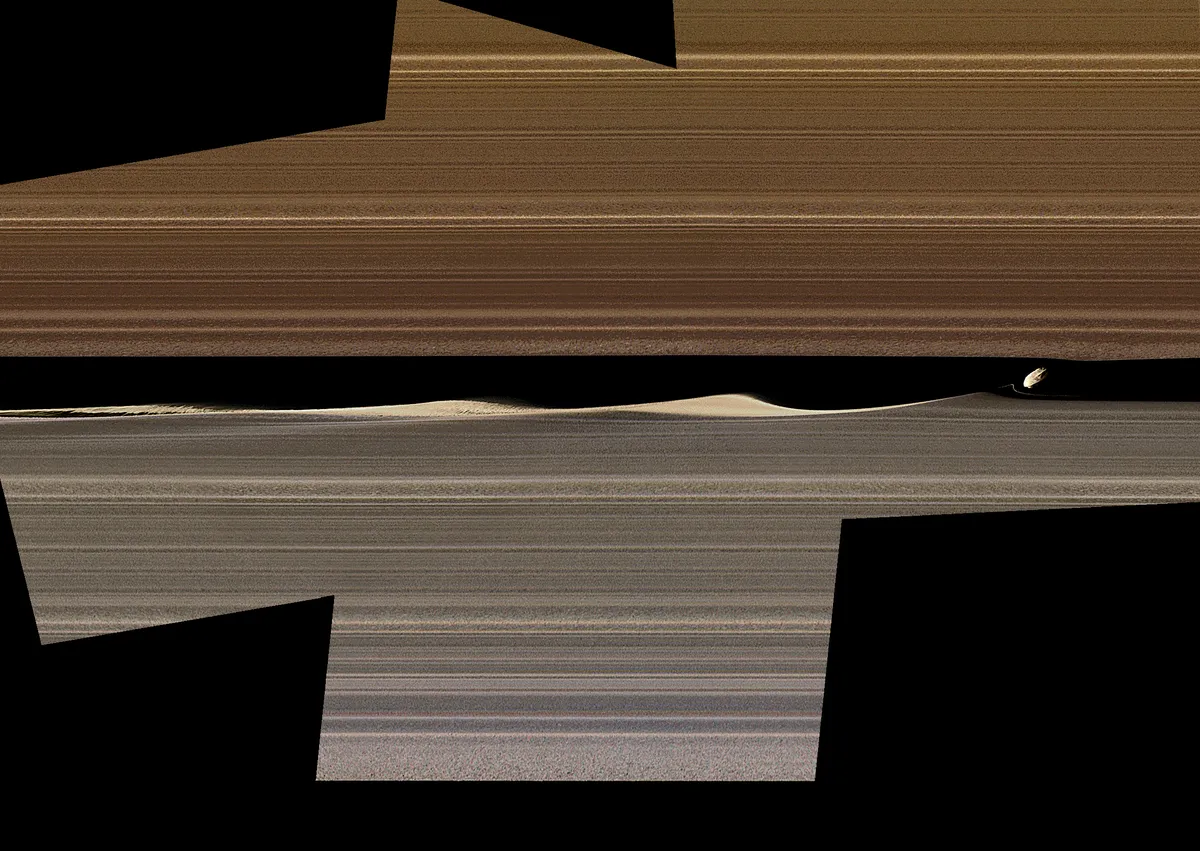

This new and improved enhanced colour image of a previously released black-and-white version shows Daphnis, one of Saturn's embedded ring moons, kicking up a series of waves as it journeys through the Keeler gap within the A ring.

Though Daphnis may be small at eight kilometres across, its presence is certainly felt within the 42km Keeler gap as the three waves are kicked up vertically.

In the colour-enhanced image, there is newly visible detail; a thin strand of wave material to the lower left of Daphnis and the intricate features of the third wave downstream from Daphnis (see below).

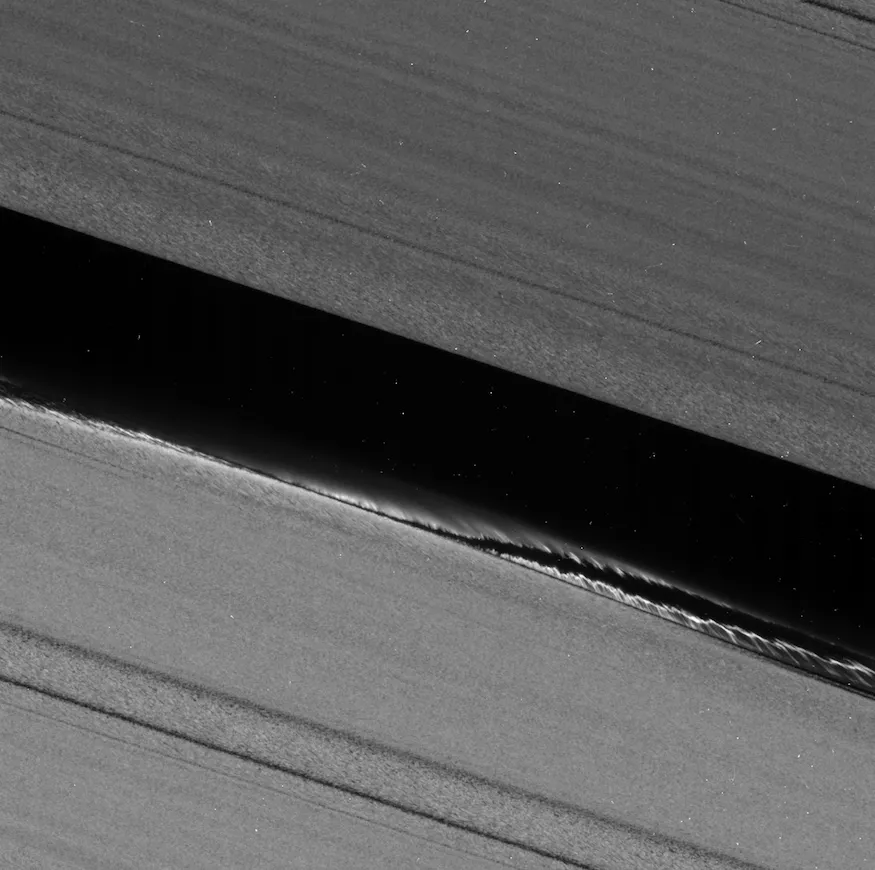

Due to the low angle at which Cassini took the image of the three waves (about 15°), foreshortening makes it difficult to view them as being material kicked up vertically, but looking at another image from Cassini, it becomes more apparent (see below).

The foreshortening has also caused Daphnis to appear larger; it is in fact five times smaller than the width of the gap.

Applying colour to the Daphnis image has not only revealed finer details but has also shed light on mysterious differences within the distinct rings.

There are noticeable colour differences between the trans-Keeler region (in the lower portion of the image) and the upper portion of the image, inward from the gap.

The exact reasons behind the different colours are currently unknown, although it has been suggested that they are caused by a difference in particle size rather than composition.

Impact evidence

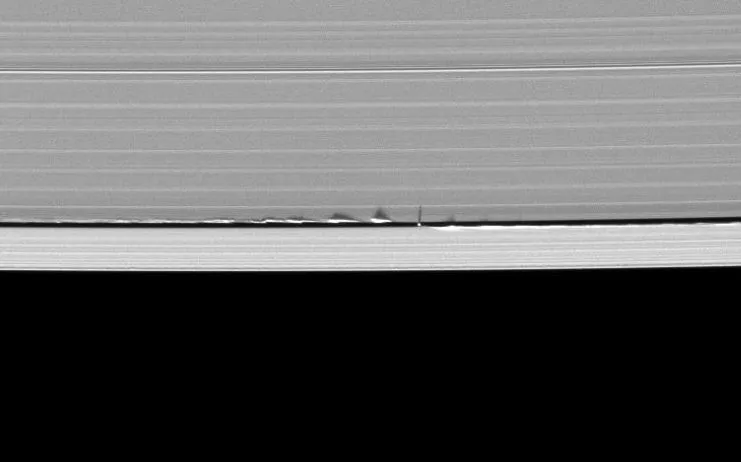

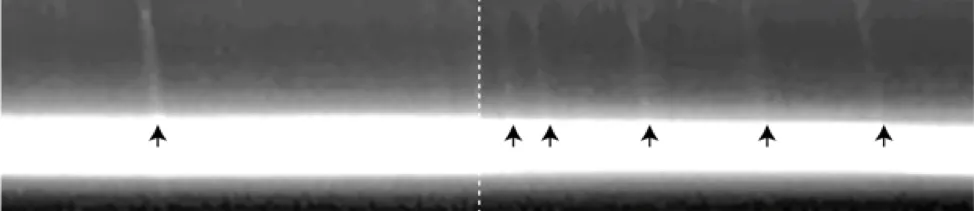

The paper also includes this image, displaying streaks (indicated with arrows) across Saturn's F ring.

Their similar length and orientation has led scientists to believe they were formed by a group of impactors that all struck the ring at the same time.

The debris is likely to have been orbiting the Sun rather than Saturn and could have been knocked off course by the gravitational effects of Prometheus, one of Saturn's inner moons.

Infrared revelations

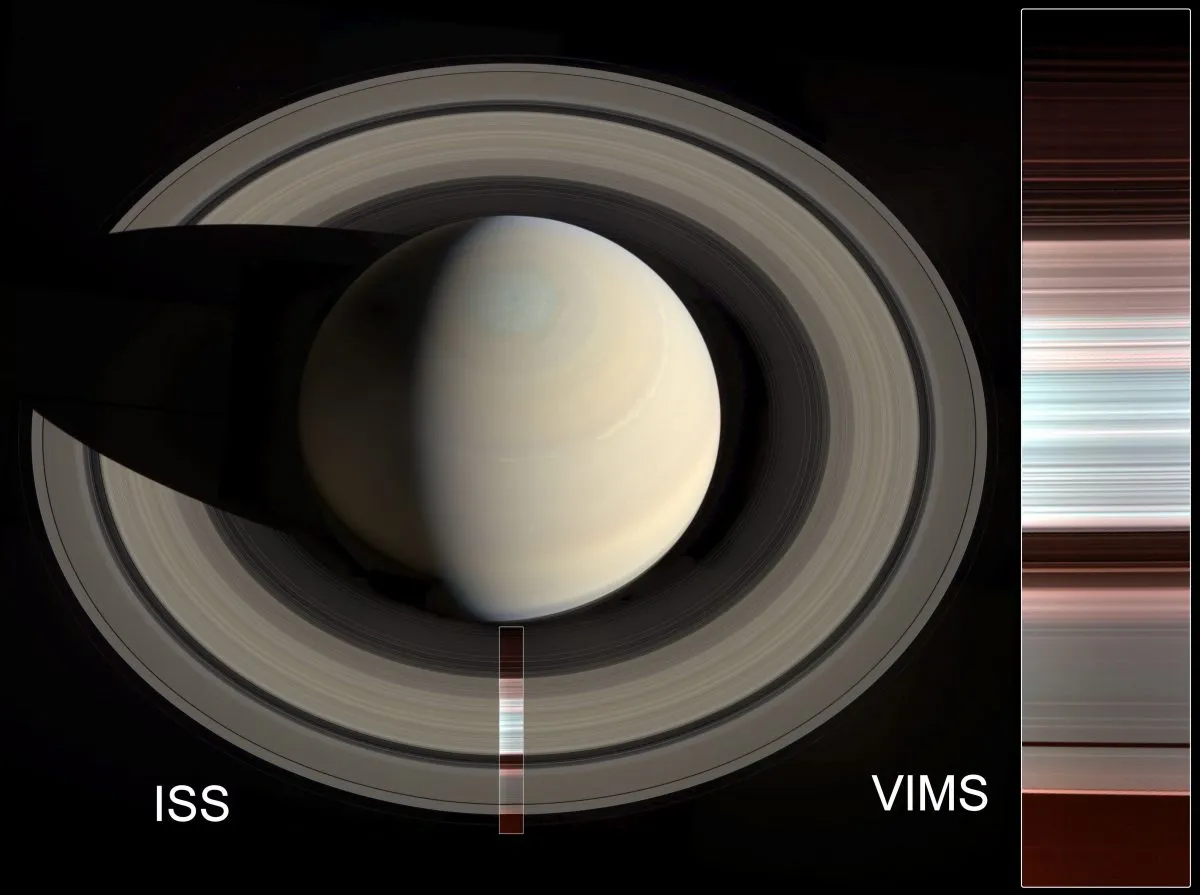

Perhaps most visually arresting is this new false-colour image of Saturn with a unique view of its rings.

Using Cassini’s Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS), a spectral map of Saturn’s A, B and C rings has been produced.

Viewing Saturn in infrared as opposed to visible light, has allowed the researchers behind the paper to reveal some interesting features of the rings.

The rings which appear blue-green in colour, primarily the A and B rings, are made from the purest water ice and/or have the largest grain size.

The rings with a reddish hue – primarily the C ring and Cassini Division - are made from non-icy material and/or smaller grain size.

Launched 15 October 1997 NASA’s Cassini spacecraft was designed to explore Saturn in more detail, along with its moons and rings.

In its lifetime Cassini travelled over 78 billion km, completed 294 orbits of Saturn and discovered six named moons.

Cassini’s contribution to science is unprecedented. It has collected over 450,000 images and 635GB of scientific data which have been used to produce almost 4000 scientific papers.

Observations made in this paper, alongside the novel images produced are helping deepen scientists understanding of not only Saturn, but our Solar System as a whole.

Cassini’s influence in science and discovery is far from over. With data from the mission still being analysed and interpreted, Cassini will continue to surprise us for many more years to come.

Find out more about the new research on the NASA website.